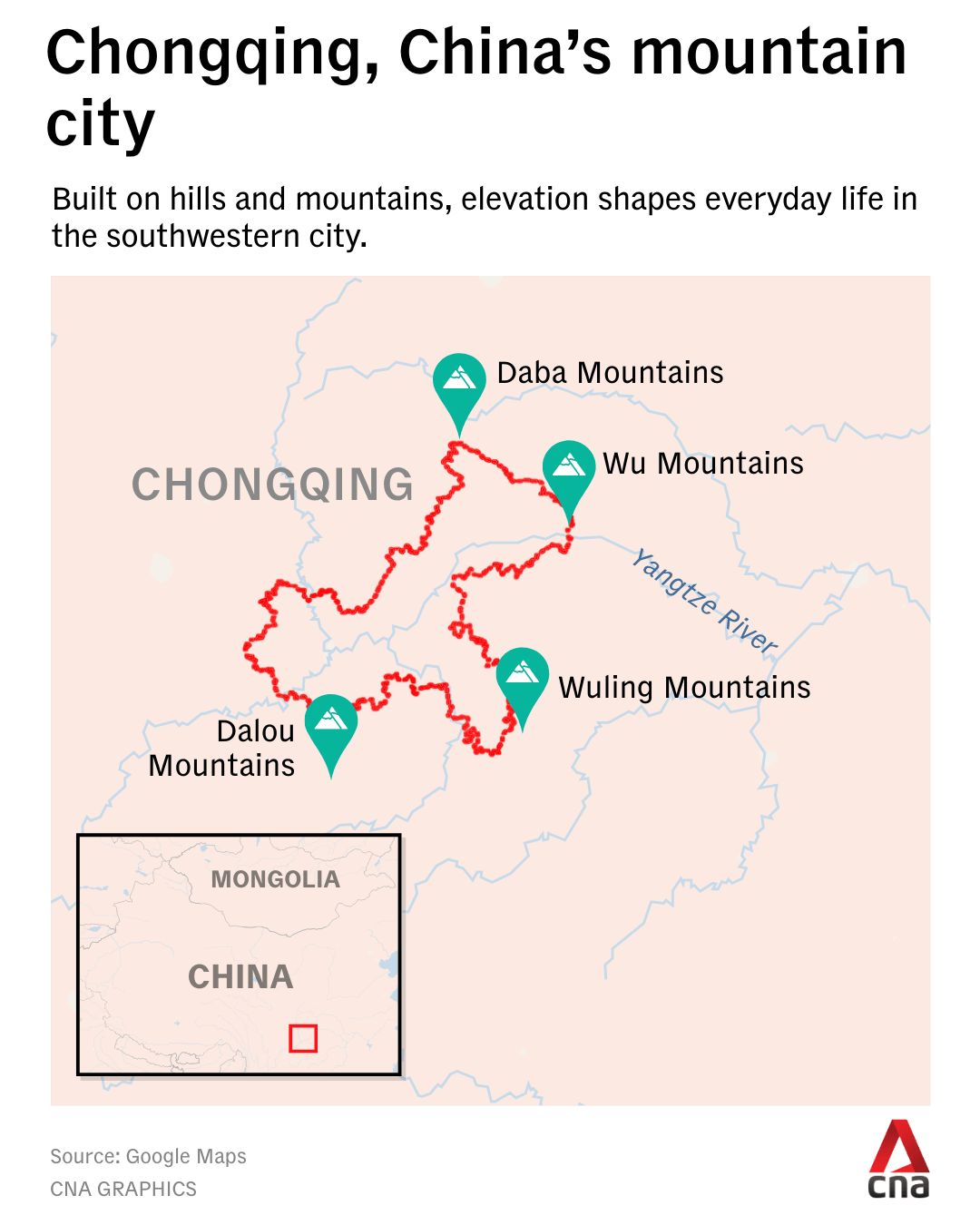

Built on hills and mountains, this '8D city' in China offers a lifestyle between levels

Steep terrain has turned elevation into a fact of everyday life in Chongqing. Beyond the viral images of its dizzying cityscape, CNA traces a quieter human story of adaptation, loss and resilience across generations.

Three decades on, Baixiangju remains a living example of how Chongqing's builders turned the city's terrain into architecture. (Photo: CNA)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

CHONGQING: Getting to Chen Hao’s apartment is an exercise in navigation and elevation.

The path winds through Gangfeng village, one of the last remaining old residential communities in Jiangbei district.

Laundry hangs between balconies. Potted plants crowd the window ledges. Elderly neighbours gather for baba - the local custom of drinking tea outdoors - often at street corners or in small open squares.

Then comes the stairwell, its steps worn smooth by decades of use.

Chen Hao lives on the third floor of a building that has never had an elevator, even though multiple flights of stairs separate each floor. The 63-year-old retiree has been making this climb for decades, since his family moved there in the 1980s.

Standing on the balcony, he gestures toward the wall of high-rises that fills the horizon. None of these buildings existed decades ago, Chen Hao pointed out.

"The view was extremely open. Originally, we could see the mountains, see Jialing River - even Shamo Stone far away," he said, referring to landmarks that once defined his skyline.

He pauses. "Now we can't see any of that."

Chen Hao’s lived experience is a small window into life in Chongqing, a city of around 32 million people, where steep, uneven terrain has turned elevation into a fact of everyday life.

The sprawling metropolis in southwest China is dubbed an "8D city" - an exaggeration of 3D - for its maze-like streets and viral visuals of roads stacked atop buildings.

Mountains account for 76 per cent of Chongqing’s land areas, followed by hills at 22 per cent, and flat land at just 2 per cent, according to academic reports.

Unlike many other Chinese cities, bicycles and e-scooters are rare in Chongqing as the streets are simply too steep.

"What's most distinctive about Chongqing is something everyone talks about," Li Weitao, an architect who has spent more than a decade designing buildings in the city, told CNA.

"When you enter a building from the street, you realise you're on the 14th floor. Then you walk down 14 floors, get to what you think is the first floor, walk out, and you're still on the street."

In a place without absolute ground, a generation that built the city’s vertical neighbourhoods watches familiar landscapes and memories disappear, even as new ones rise in their place. At the same time, younger residents are coming of age in those same layered quarters.

Through the lives of residents across generations, CNA traces stories of adaptation, loss and resilience in a city shaped as much by elevation as by time.

SHOULDERING THE CITY

Before the escalators came, before the malls and the modernisation, Chongqing moved on human backs.

Xu came to the city’s urban core from rural Dianjiang county - about 120km to the northeast - more than 30 years ago.

Aged 63, he is among Chongqing’s dwindling ranks of porters, known locally as "bang bang jun". The term comes from the bamboo poles used by these porters, primarily men, to carry goods across their shoulders.

At their peak in the 1990s, as rural migrants flooded the city, the ranks of "bang bang jun" were estimated at between 300,000 and 500,000.

Today, their numbers have dwindled to just a few thousand, according to various reports - a decline driven by better roads, delivery apps and the simple fact that few young people want the work.

Xu did not start out as a porter. "At the beginning, I was shining shoes, together with fellow villagers," he told CNA.

The earlier roads were unpaved, thick with mud.

"The roads were terrible back then. That's why the shoe-shining business was good at the time. Shoes got dirty easily."

Later, as wholesale markets grew and shops couldn't deliver fast enough, he switched to carrying goods.

The city he entered was unrecognisable from today. Major malls like Grand Ronghui and Shengming had not been built.

Liangjiang, now a sprawling state-backed development zone, was not yet on the map.

As a porter, this meant long days of backbreaking work, he recalled.

"There were very steep slopes. Carrying loads uphill was 'nao huo de hen' (extremely brutal)," he said.

"In the past, even big loads were carried by 'bang bang'. Roads weren't connected and transport wasn't convenient - everything relied on human labour."

While the loads have become less punishing, Xu’s work endures.

Now, he wakes before dawn, arrives at the wholesale market by 6.30am and hauls goods until it closes at 2pm. On good days, he earns between 100 yuan (US$14) and 200 yuan - meaning even a full month of such takings would barely match Chongqing's minimum monthly wage of around 2,300 yuan.

"Hard manual labour never makes much money. It's just to scrape by. Barely enough to live," Xu said.

Yet in his view, the labour remains indispensable.

"Without 'bang bang', how do goods get moved out? Doesn't it still require human labour?"

LIFE BETWEEN LEVELS

The work of carrying goods may be fading, but vertical movement remains woven into daily life - especially for the young.

At 7.45pm, the stairs beside Kaixuan Road Elevator rise steeply into the evening haze. The lift - China’s first urban passenger elevator - links the upper and lower halves of Chongqing, and spans 11 storeys.

At this hour, students from nearby Fudan Secondary School are making their way up. The elevator ride only costs 1 yuan, but some have chosen the stairs.

Bao, 14, sometimes takes the lift, but not that particular evening.

"There are too many people - the elevator down there is super crowded," said Bao, who identified herself only by her surname. "And because you get squeezed going up - squeezed really badly."

During exams, when time is tight, Bao doesn’t bother waiting for the elevator. "I just run up and down directly."

Shen Xiwang, 13, has a different reason for taking the stairs.

"My family’s (financial) situation isn't very good … so I use less money," he told CNA.

"Originally, (my friends) were also going to take the elevator, but I told them to come and keep climbing with me."

None of the students CNA spoke to was fazed by the climb.

"In Chongqing - everywhere you go, you're climbing stairs," said another 14-year-old student, surnamed Wu.

"Mountain city. That's the characteristic of this city."

For those who grew up elsewhere, the adjustment to Chongqing’s vertical rhythms can be jarring.

Gong Yupeng arrived from Qingdao 18 months ago, following his girlfriend - a nurse at a children's hospital - across 1,800km by car. He calls himself a "Shandong man becoming a Chongqing son-in-law".

Gong, a business consultant in the design industry, learned quickly that Chongqing has its own directional logic.

"People here don't say east, south, west, north - they only say up and down," he said.

"Here, buildings face every direction, so it's easy to lose your sense of direction."

Gong also quipped that navigation apps cannot be trusted.

"You turn on navigation and it feels really close, just a few steps, maybe a few hundred metres. But once you actually walk, you realise you have to make a huge detour down."

When he loses his bearings, Gong calls a taxi.

"I put a lot of faith in the 'yellow Ferraris'," he said, using a local nickname for Chongqing’s yellow cabs. "They can take me out of there without relying on navigation."

But despite some pains, Gong has come to love the climb.

"I think stairs are okay for me, because I like exercising. Going up and down - I think it's kind of fun. It's like walking through a maze: after you go down a small path or go up a flight of stairs, it's a completely different scene. I think that's a little surprise Chongqing gives me," he said.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF ALTITUDE

What sometimes feels like improvisation is, in fact, built into the city itself.

Li, the architect whose firm has worked on several renewal projects across Chongqing, says the city's verticality is most extreme in Yuzhong district - a peninsula wedged between two rivers where an entire mountain is wrapped in buildings.

"The entire spatial structure is much more three-dimensional," he explained. "Every single project encounters very complicated site conditions and height-difference relationships."

At first, this was about passively solving problems. Over time, it evolved into actively using the terrain.

"If I have multiple ground floors," Li said, "then the architectural space becomes much more interesting."

A striking example is Baixiangju, a 24-storey residential complex completed in 1993. It has no elevators.

The project comprises six towers, with more than 500 households stacked into the mountainside.

From higher levels, stairways lead into other stairways, paths and actual roads that are narrow and winding. Although clearly within a residential complex, the setting feels unexpectedly precipitous.

Mid-level aerial corridors connect the blocks, forming a web of passages lined with beverage stalls, cafes and lamb soup restaurants.

Inside, residents go about their lives in a simple, unhurried rhythm.

The building was designed to exploit a loophole, Li noted.

"Back then, buildings over 10 storeys were required to have elevators," he said, adding that Baixiangju avoided crossing that threshold by working with the terrain.

Three exits - on the 1st, 10th, and 15th floors - each lead to different streets, different neighbourhoods.

“No matter which entrance you use, you're never actually above 10 storeys, so they didn't install elevators."

By creating entrances at three different levels, Baixiangju's developers ensured no single access point exceeded that limit - a cost-saving workaround. This would be impossible under current building codes, which mandate elevators for structures with at least four floors.

One detail captures the strangeness: along the corridors, shops that appear side by side display different floor numbers.

A lamb soup restaurant might be marked as on the 11th floor; a drinks shop a few metres away, the 12th.

They belong to different blocks, each starting from a different ground level.

But not everyone is enamoured by Chongqing’s verticality. For those who maintain its infrastructure, the extraordinary has long since become ordinary.

Pang, 27, repairs elevators for a living. Asked whether Chongqing's terrain creates special problems, he shrugged.

"Elevators are basically all the same; the systems are pretty similar," he said.

"Other places have a lot (of elevators) too - it's just that Chongqing has a bit more."

Is the work hard? "Every job is tough," he said. "It depends on the level of hardship and the kind of hardship."

THE COST OF GOING UP

In Gangfeng village, the afternoon light falls across the open square where neighbours have gathered for their customary tea drinking.

"Every day the baba is full of people," observed Chen Shijin, 92, the father of retiree Chen Hao. The elder Chen himself occasionally participates.

Chen Shijin entered Chongqing’s Third Steel Plant - one of several steel plants that once anchored the city’s industrial base - in 1954. He retired in 1985.

The factory site was once located on the land below their family home.

"When we were children, going down from here meant walking down a slope to the river," Chen Hao said.

“Look at the roads now - they've changed completely."

Development has redrawn the city’s features, but also its social fabric.

The junior Chen worries that the community spirit he grew up with is being eroded elsewhere as neighbourhoods like his give way to high-rises.

"If you live in a new building now, you go upstairs and you don't know who has what surname, what they do for work, or how old they are," Chen Hao said.

"You have no idea. Only the old neighbours from before know these things."

He is direct about what he misses.

"Honestly, I still miss the earlier era … there was strong human warmth - (a) strong neighbourly feeling."

Li, the architect, has a theory why. "Before the real estate boom of the past 20 years, there were buildings without elevators that used height differences," he said.

"For example, there might be a road cutting through the middle of a building, with a retaining wall in between that's hollow, and some skybridges leading into the building."

"These skybridges would form very small, shaded spaces. They're tiny, but are some of the very few public spaces where neighbours can interact."

Li added that modern high-rise buildings lack public space. "And when public space is lacking, neighbourly relationships become distant."

The generational divide in the Chen family runs against expectation. As the son mourns what is fading away, the elder Chen is pragmatic.

Chen Shijin wants the building rebuilt. "To be honest, this building should be demolished," he said, pointing to the hassle of living in a walk-up.

"What is there to be reluctant about demolishing? Once you adapt to the new environment, it's the same."

His son understands what demolition would cost.

"What we'd be most reluctant to lose is this kind of neighbourly bond," Chen Hao said. "Other than that, nothing much."

While some old neighbours have long moved out, they stay connected through a group chat.

“Whenever there's a birthday, everyone gets together," Chen Hao said.

Li, the architect, has spent years thinking about what demolition costs a city.

"Memory is extremely important … (it’s) part of human life," he said.

“Destroying someone's lived experience is no different from taking their life - from a certain perspective, it's a very serious matter."

THE CITY KEEPS CLIMBING

But there are places in Chongqing where old and new have found balance.

In Nan'an district, Houbao was a lively commercial zone in the 1980s and 1990s - a transport hub that was once home to the Yangtze River Hotel, the first four-star hotel in western China.

As Chongqing's development shifted to newer city centres, Houbao was left behind due to reasons such as underinvestment and ageing infrastructure.

But a government-led urban renewal project launched in 2022 brought it back - not through demolition, but careful intervention.

Elevators and other infrastructure were upgraded and building facades were refurbished. Li's firm, which worked on the project, focused on inserting small commercial spaces and community areas into underused corners.

At the heart of the renewal is a community lounge - a shared space where residents gather and activities are organised.

"Through the creation of public space, we both respected the original residents' living space and introduced new business formats for young people, allowing two groups that previously had little interaction to form connections."

After young people started coming, he said, the relationship between them and the original residents became "surprisingly harmonious".

In present-day Houbao, yellow banyan trees line pavements. Elderly residents go about their exercise routines at the morning square.

Along a covered walkway, younger people gather with coffee, gazing at the river. Trendy cafes sit beside corners where the elderly play mahjong.

Like the rest of Chongqing, the ranks of "bang bang jun" here have thinned with improved roads and the spread of logistics and delivery services. Groceries and other daily necessities are now routinely delivered to doorsteps.

Li sees irony in progress: When people talk about artificial intelligence and technology, he said, they initially hope these tools will do remarkable things.

"But in the end, what they (tend to) replace first are the most basic jobs. The first industries hit by technology are often the ones involving hard physical labour," he said.

"That’s something people didn’t fully anticipate, and it’s very cruel."

And yet something endures.

"I think it's the spirit of Chongqing people - building and living in mountainous terrain," Li said.

"They didn't avoid the challenge … it's not 'this is hard, so I'll go somewhere easier'. It's 'there's difficulty, so I overcome it'. I think that's a defining characteristic of Chongqing - not afraid of hardship or struggle."

That spirit is still visible in people like Xu, the veteran porter.

After more than three decades of hard work, he plans to stop in another year or two.

"I'm already over 60," he said. "What more should I do?"

For now, he keeps going.

Xu hoists the bamboo pole onto his shoulders and heads off - up a ramp, down a corridor, through the crowd.

His body still knows every shortcut in the vertical city. Soon, that knowledge will exist only in memory.

But the city keeps climbing.