IN FOCUS: GST, wealth and carbon taxes – Singapore’s possible tax priorities for Budget 2022 and beyond

(Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

SINGAPORE: Following two years of major spending to contain COVID-19's economic impact and with the need to invest in longer-term social infrastructure, this year's Budget will likely see the spotlight being shone on the issue of fiscal sustainability, economists and tax experts said.

Beyond Budget 2022, the national conversation about possible changes to Singapore's tax system is set to continue, they added.

Taxes will be in focus when Finance Minister Lawrence Wong delivers his Budget speech on Friday (Feb 18), these observers said. One of which, to no surprise, will be the long-planned Goods and Services Tax (GST) increase that the authorities have described as critical for bringing in the additional revenue that Singapore needs for an ageing population.

“The past two years of pandemic has taken a huge toll on Singapore’s fiscal resources, and there is now an urgent need to refocus on fiscal sustainability,” DBS senior economist Irvin Seah said.

KPMG Singapore’s tax partner See Wei Hwa noted that Budget 2022 will be “one of the more tax-focused budgets in recent years”.

“(People are watching) for any changes to the tax regime, especially given that the Government has tapped more than S$50 billion of the reserves over the last two years,” he said.

“Now that we are emerging from COVID-19, the question is how can the Government make sure that its fiscal condition will be sustainable over the longer period?”

RISING EXPENDITURE

Singapore is not alone.

Other countries, such as the United Kingdom and Indonesia, have also started mulling tax hikes. As the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) pointed out in a report last year, the pandemic “has caused a significant deterioration in public finances, which calls for a rethink of tax and spending policies once the recovery is well underway".

The fight against the pandemic over the last two years has seen Singapore accumulating budget deficits of S$75 billion, while drawing the equivalent of about 20 years of fiscal surpluses from past reserves.

Prior to COVID-19, public expenditure was already on the rise with the Government’s revenue struggling to keep up.

Over a 10-year period from FY2010 to FY2019, yearly expenditure on government administration, economic development and social development rose by an average of 9.1 per cent, 7.7 per cent and 7.4 per cent respectively, according to a report from UOB.

On the other hand, operating revenue – derived largely from taxes – grew at a slower rate of 6.6 per cent per year over the same period. According to the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS), tax collections accounted for 73.6 per cent of the Government’s total revenue in FY2020.

As a result, the Government’s primary balance, defined as operating revenue minus total expenditure, has been negative in five out of the past six fiscal years, noted UOB economist Barnabas Gan.

“This suggests that tax receipts including that of personal income, corporate and GST have not been enough to cover the rising expenditure costs,” he said.

The “only way” to close this deficit in the primary balance has been to tap on the net investment returns contribution, noted Barclays economist Brian Tan. “This is not sustainable. You’ll ideally want that to be a bonus that you can do without, instead of something you’re absolutely dependent on for fiscal sustainability.”

Moving forward, the Government’s spending will only go up in the face of challenges such as a rapidly ageing population and climate change.

For instance, Singapore’s healthcare spending has tripled in dollar terms over the past decade, now standing at 2.2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). This expenditure is expected to hit 3 per cent of GDP by 2030, and will “keep rising” even beyond that, authorities have said.

Such longer-term needs will incur “significant costs” and require a sustainable source of revenue, said Mr Seah.

“Unfortunately, there aren’t many options available when it comes to reliable sources of tax revenue,” he added, noting that there is “limited” room to tweak corporate and personal income tax rates without diluting the country’s overall competitiveness.

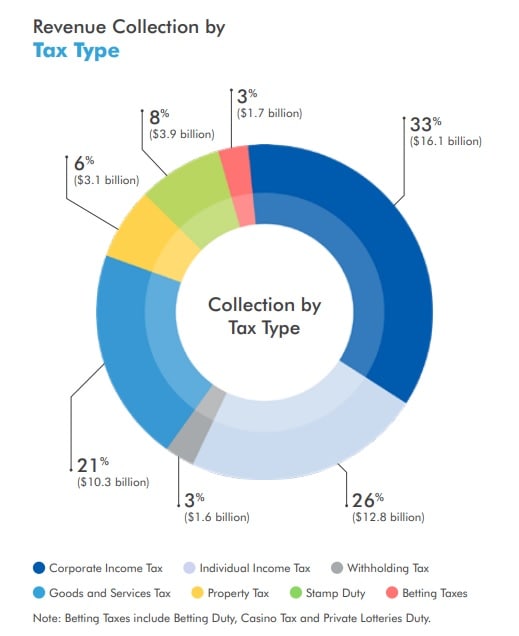

Corporate and personal income taxes have been the country’s top two biggest sources of tax revenues, typically making up more than half of total annual tax collections. GST, which accounts for slightly more than one-fifth of tax revenue on average, comes in third.

This explains the choice of a GST hike to keep Singapore’s fiscal position on a more sustainable footing, experts said.

Meanwhile, discussions about wealth taxation and a higher carbon tax have grown over the years.

As Singapore navigates the post-pandemic world, experts said it will need to find the sweet spot in meeting economic and social goals, while balancing public finances.

“Singapore’s focus will need to involve building a progressive economic and tax structure that allows the country to take bold steps to grow, while mitigating transition pains and ensuring that no one is left behind,” said KPMG Singapore’s partner and head of tax Ajay Kumar Sanganeria.

GST HIKE: NOT IF, BUT WHEN

The GST was first introduced in Singapore in 1994 at the rate of 3 per cent. It was then raised to 4 per cent in 2003, 5 per cent in 2004, before being increased to the current rate of 7 per cent in 2007.

The GST, being a broad-based tax applied on a wide range of goods and services and on anyone who consumes regardless of age or income, is less affected by business cycles and ageing demographics. This means it is more stable and predictable, experts said.

It is also seen as an efficient tax with a low cost of administration.

Singapore first announced its plan to raise the GST by two percentage points, from 7 to 9 per cent, in 2018. The increase was deferred last year in view of COVID-19, but Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong indicated in his New Year message that the Government will “have to start moving” on the planned hike now that the economy is on the mend.

The spectre of rising inflation is unlikely to derail the GST hike, said experts, adding that there is never a good time to raise taxes.

Mr Tan, who believes that the increase could happen as early as April, said: “We are bound to have an increase in inflation, regardless of when they pull the trigger. The timing is not going to change things materially.”

Mr Seah reckons the tax change may kick in by July, going by how the GST hike in 2007 took effect about five months after it was announced in that year’s Budget.

Others say businesses will need time – from three to six months or even longer – to adjust their budgeting and price displays, hence the “window period” for change may even stretch until early next year.

With the same consideration in mind, experts are also expecting the two-percentage-point increase to be done at one go, as staggering the hike will result in inconveniences for businesses.

“It’s like removing a plaster,” said PwC’s tax leader Chris Woo. “Better to just do it quickly and get it up to 9 per cent.”

DBS estimates that the two-percentage-point hike in GST will yield an additional S$3.2 billion to S$3.6 billion in tax revenues a year.

That said, the Government is aware of concerns that the tax increase will add to the cost of living.

It has set aside a S$6 billion Assurance Package which it said will cushion the impact by at least 5 years for most households.

Earlier this week, Mr Wong, the finance minister, reiterated that there will be “a comprehensive set of measures” to support lower- and middle-income households, as well as retirees.

Mr Tan expects the Assurance Package, which was first announced in Budget 2020, to be bolstered with “a little more support”.

“I don’t think they will stick to what they have set aside. I think they will supplement it, and the question is what form that will take,” said the Barclays economist.

“If you go by 2007’s offset package which included cash handouts and subsidies that are geared more towards the lower-income groups, I think you will see a similar pattern this time.”

| Financial year | GST collections |

| 2016/17 | S$11.1 billion |

| 2017/18 | S$11 billion |

| 2018/19 | S$11.1 billion |

| 2019/20 | S$11.2 billion |

| 2020/21 | S$10.3 billion |

Source: Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore

WEALTH TAX: A TRICKY TIGHTROPE

Away from GST, the discourse on wealth taxes has gathered momentum, with various politicians weighing in on the matter.

Mr Wong, for one, has addressed the issue on several occasions, stressing that Singapore is already taxing wealth in various forms such as property tax and stamp duties on residential properties, as well as additional registration fees on motor vehicles.

But to guard against rising wealth inequality, the Finance Minister has said the Government is studying how to expand its system of wealth taxes in ways that “add to (Singapore’s) revenue resilience without undermining overall competitiveness”.

Speaking at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in November last year, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said while the Government wants a wealth tax in principle, it is “very hard” to do so in forms other than property tax. To this end, it will need to find a tax system that is progressive and “people will accept as fair”.

Taxes on privately held wealth can help Singapore to “recoup some of the fiscal damage” and address a widening wealth gap, according to Grant Thornton Singapore.

“The Government has already stated that raising GST will not be sufficient … They can certainly increase other forms of existing taxes, but these do not broaden the tax base (or) help deal with the increasing wealth gap,” said the professional services firm’s private clients and employer solutions partner Adrian Sham.

“Wealth taxes can tick all of these boxes.”

But rolling out a “pure wealth tax” – one that taxes the net wealth of an individual – would be “a death wish” for Singapore, given difficulties in implementation and the possibility of spurring a capital flight, said Mr Sham.

“As with any other tax policy decision, it is a fine balance between milking the cow versus killing the goose that is laying the golden egg. This is no different when considering new taxes on wealth,” he added.

As such, Grant Thornton is suggesting that wealth taxes be directed at investment properties via a combination of a real property gains tax for residential property and a deemed rental income tax for vacant residential property.

“Singapore real estate provides a safe-haven parking lot for foreign wealth as properties can be perpetually left empty,” said Mr Sham, adding that these properties do not contribute to the economy unless they are used productively.

Introducing a deemed rental income - in effect, the amount an owner could have made if a vacant property was rented out - for unoccupied residential property owned by both local and foreign individuals, would drive some owners to sell or rent their property out. Those who choose to leave it empty would also be paying more taxes through tax on the deemed rental income.

“It is also difficult to evade or plan around, as the property is hiding in plain sight and cannot be moved overseas," he added.

Other experts also reckon that changes in wealth taxes, if any, would likely be property-related such as higher buyer’s stamp duty or property tax rates for luxury residential properties.

Such targeted moves are less drastic and can help mitigate the impact on Singapore’s status as a wealth management and financial hub.

EY’s Asean private tax leader Desmond Teo pointed to how Singapore has been the largest recipient of foreign direct investments into the region, accounting for two-thirds of such inflows in 2020. These investments have generated local economic spin-offs, be it in partnerships with local businesses or helping to build up Singapore’s financial markets.

PwC’s Mr Woo concurred, noting that the financial services industry has been a key pillar of the Singapore economy. The sector has also continued to see strong growth amid the pandemic.

“One of the things about introducing new taxes is, are you going to hurt what's not broken? We’ve been the beneficiaries of people moving wealth into Singapore so if we try to squeeze the golden goose too hard, it could fly away,” he said.

Other factors, such as effectiveness and ease of execution, will also have to be considered.

Globally, despite louder calls for wealth taxes, many countries have in fact been moving away from them. From 12 countries in 1990, the number of OECD countries levying net wealth taxes has since dropped to four due to “very low” collections, administrative concerns, as well as observations that such taxes have “frequently failed to meet their redistributive goals”, according to a report by the OECD.

Back in Singapore, estate duty was abolished in 2008 for similar reasons, experts said.

“Adjusting for any abnormal years, what we have seen is that estate duty on average accounts for less than 0.5 per cent of total tax collections in Singapore in a year,” said Mr Teo. “From that perspective, estate duty may not be able to contribute as much … to meet the increasing operating expenditure.”

Introducing an inheritance tax is also a “complex endeavour”, said Mr Yeoh Lian Chuan from Withers KhattarWong, as it would have to be complemented with lifetime gift taxes to prevent the rich from transferring a substantial amount of their wealth to the next generation before they pass on.

Another important point to consider is that many Asian countries do not have estate or inheritance taxes.

“Singapore may not want to be the first mover in the opposite direction, especially if the revenue raised is not substantial,” said Mr Yeoh, partner of private client and tax at the law firm.

CARBON TAX: MORE ROOM TO GROW?

Changes are also afoot for Singapore’s carbon tax.

The current rate of S$5 per tonne on firms that emit at least 25,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas was first implemented in 2019, making Singapore the first country in Southeast Asia to roll out such a levy.

Authorities have acknowledged that the existing rate, which is set for until next year, is “too low”. The revised rate for 2024, as well as what to expect until 2030, will be announced at the upcoming Budget.

At a recent parliamentary motion on climate change, some Members of Parliament called for the carbon tax to be raised “significantly” or have its scope widened to include smaller emitters, among other suggestions.

Tax experts expect the carbon tax increase to be between S$10 to S$15 per tonne – a range previously announced by the Government – although there might be “room to grow” in the longer run.

“The rates in Singapore are on the lower side, compared to other countries like in Europe so it seems like there’s certain room to grow, especially as people become more environmentally conscious,” said Mr See from KPMG.

At the same time, other regional and global developments are under way. The European Union’s plan to impose the world’s first carbon border tax on imports, for one, may require Singapore to “sit up and rethink if (it) should bring on board something like that”.

“Because if we don’t tax that supply chain, another country will,” said Mr Woo.

Several Southeast Asian countries are also mulling carbon taxes, such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

“Singapore's carbon tax rate should be based mainly on what it takes to get domestic businesses to decarbonise, but we can add efficiency and scale if ASEAN moves forward together given the region's economic interconnectivity,” said Singapore Institute of International Affairs’ deputy director for sustainability Gan Meixi.

That said, experts do not see carbon tax as becoming a big source of revenue. At the current rate, the Government has said that it expects to collect about S$1 billion from 2019 to 2023.

The tax serves more “as a nudge” to get firms to shift to greener alternatives, experts said.

“I don't see carbon taxes as a big revenue generator,” Mr Woo added. “But if you’re trying to improve or change behavior, carbon taxes will be a way of helping that.”

Carbon tax rates around the world

A carbon tax sets a price that companies must pay for the greenhouse gas emissions that they emit.

Such a tax increases the prices of fossil fuels, electricity and general consumer products hence promoting the switch to lower-carbon fuels in power generation, encourage energy conservation and the use of cleaner vehicles, among other things.

| Country | Carbon tax (US$ per tonne of greenhouse gas emission) |

| Sweden | 137 |

| Switzerland | 101 |

| France | 52 |

| Ireland | 39 |

| Netherlands | 35 |

| Portugal | 28 |

| Spain | 18 |

| South Africa | 9 |

| Argentina | 6 |

| Chile | 5 |

| Japan | 3 |

| Ukraine | 0.3 |

Source: World Bank

CORPORATE TAX: SOME UNCERTAINTIES AHEAD

Meanwhile, corporate tax – which has been Singapore’s biggest source of tax revenue making up roughly 30 per cent of total taxes collected – may face some uncertainties amid a global tax reform.

As of last November, more than 140 countries and jurisdictions, including Singapore, have endorsed an agreement brokered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development to overhaul global corporate tax rules and fight what is known as domestic tax base erosion and profit shifting.

The deal comprises two main pillars – firstly, to ensure businesses pay taxes in countries where they earn their profits, regardless of whether they have a physical presence. Secondly, to set a minimum corporate tax rate of 15 per cent so as to curtail profit shifting to lower-tax jurisdictions.

The pact is due to take effect in 2023 although key details, including how to calculate the pot of profit that is to be taxed, remain in the works, according to media reports.

Tax experts said the first proposal, which looks to reallocate profits to markets where end consumers are located, may result in excess profits of regional firms based in Singapore being allocated elsewhere.

The setting of a global minimum corporate tax rate may also "blunt" the effectiveness of tax incentives that Singapore uses to attract foreign direct investments, they added.

Currently, Singapore’s headline corporate tax rate is at 17 per cent but the effective tax rate of many businesses may be lower than that, or even the proposed global minimum, due to tax incentives awarded to those seen as beneficial to the country’s economic development.

That said, the eventual impact of this global tax reform on Singapore remains difficult to predict as the country’s long-term attractiveness to multinational companies has always been more than just taxes, experts said.

“Singapore does have quite a lot of other strengths that it can continue to ride on in terms of retaining investments and jobs,” said EY’s Mr Teo, citing attributes such as rule of law, a stable government and a trained workforce.

“All these economic benefits and strengths that Singapore offers remains.”

In fact, there may even be a near-term boost in revenue if tax incentives to corporates are withdrawn, experts said.

| Financial Year | Corporate income tax collection |

| 2016/17 | S$13.6 billion |

| 2017/18 | S$15 billion |

| 2018/19 | S$16.1 billion |

| 2019/20 | S$16.7 billion |

| 2020/21 | S$16.1 billion |

Source: Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore

With inflation and rising costs of living, is 2022 really the best time for a GST hike? Tax experts debate the trade-offs on CNA's Heart of the Matter podcast:

Still, the consensus is that Singapore cannot afford to let its guard down and will have to work on sharpening its competitiveness on non-tax fronts, particularly in alleviating business costs, Mr Woo noted.

Singapore can also develop itself as a hub for sustainability and carbon services, as well as emerging areas like health technology, in order to keep attracting foreign direct investments.

“Companies come to Singapore for many more reasons than just tax so we need to find ways to keep getting companies to bring in jobs and generate economic activity here,” he said.

The emphasis on keeping the economy humming extends to the broader goal of ensuring fiscal sustainability.

“The best form of tax collection is basically growing the economy. You grow the pie bigger, you can cut out a bigger slice,” said Mr Woo. “In the long term, Singapore would be best served if the expected increase in government spending is funded by economic growth.”