'We want you to still feel at home': How NLB designs its libraries to be more than just for reading

Designing a library where everyone feels welcome requires attention to the tiniest details, including the space between entry gantries and the brightness of its lights.

Punggol Regional Library as pictured on Aug 1, 2023. (Photo: CNA/Grace Yeoh)

SINGAPORE: Visitors to Punggol Regional Library may have noticed that Singapore's newest library is not as brightly lit as other libraries – and this was a deliberate decision.

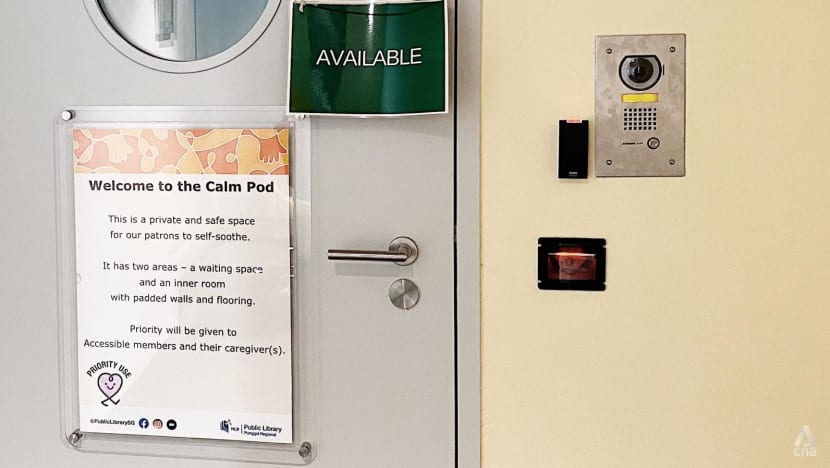

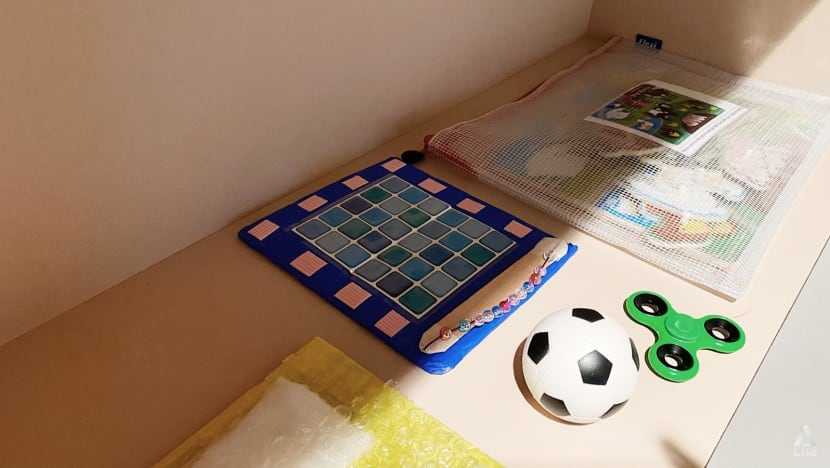

When the five-storey library officially opened in April, the spotlight was on its accessible features for people with disabilities. Among these, a wheelchair-accessible book borrowing station, an accessible collection including books in Braille, assistive technology devices and Calm Pods.

But creating a truly inclusive space meant its assistant director Verena Lee also had to pay attention to "standard" features such as lights. The differing feedback on lighting, however, initially took her by surprise.

"When we invited people with disabilities to come to give an assessment of space, I had (someone) with visual impairment. He said, 'Big, bright, bold.' And then I had (an autistic advocate who wanted things to be) dark, as she didn't want things to be too bright," she recalled.

Ms Lee settled on a middle ground and gave visitors options in the end. "If you find it too bright, we have darker areas. We have super dark ones (too), like in the Calm Pods," she said. "But if you find it too dim, then you find a seat with more light."

As the head of accessibility for the National Library Board (NLB) too, she simply wants visitors – all of them – to feel welcomed. And she’s not alone.

NOT JUST FOR READING ANYMORE

NLB doesn’t want libraries to be places solely for reading anymore, said Mr Wan Wee Pin, director of planning and development, whose role involves looking into how spatial design can achieve that.

Adding that library spaces must go beyond providing information, he noted that information is, after all, readily available on our phones, as the COVID-19 pandemic showed “very, very clearly”.

“Reading, in a way, has slowly evolved for us into more like a mission of getting people to learn – and learning can be through different means. It doesn’t necessarily have to be through reading,” he said.

Such plans might be a timely move, in light of decreasing reading enjoyment among students according to the 2021 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study.

The latest run of the international study collected responses from 6,719 Primary 4 students in Singapore. It found that the proportion of students who reported “enjoying reading a lot” fell to 51 per cent, compared with 55 per cent in 2016 and 60 per cent in 2011.

The Education Ministry noted in May that these observations are "not unique to Singapore”. The decline in reading enjoyment “may in part be driven by the rapid proliferation of other forms of entertainment and content formats (for example, social media) over the last decade".

Nonetheless, added Mr Wan, this “new direction” for libraries to move beyond reading as its sole purpose requires NLB to focus on “creating different experiences within our spaces” where visitors can “come, discover and learn”.

LIBRARIES AS AN "EQUALISER"

These considerations are in line with libraries being an “equaliser” – a key role in NLB’s Libraries and Archives Blueprint 2025.

Equality at Punggol Regional Library, for example, meant building a place where people with disabilities and members of the public felt comfortable using, said Mr Wan.

The interaction between both groups was key, he added. “We didn’t want to demarcate zones, where ‘this is the PwD zone, this is the public zone, and neither the twain shall meet.’”

And so, an advisory committee of people with disabilities was consulted from the planning stages. The Tampines Regional Library was the newest library at the time, so the committee was asked to pick out "pain points" from that library or other public spaces they had visited, said Ms Lee.

As a result, "intentional" design choices were made for the Punggol library, including details such as the space between shelves and the width of each entry gantry.

The latter, for instance, took the same dimensions used at Thomson-East Coast Line MRT station gantries, which the team found "very wide" and suitable for large strollers too.

"What's good is that every one is wide enough for wheelchair users to pick. It's not like 'this is your lane, this is my lane' ... This is ours, and we can use whichever we want," Ms Judy Wee, a wheelchair user and member of the advisory committee, told CNA.

PROVIDING OPTIONS

With other features in the library, accessibility simply means having options.

For instance, the study area has a couple of tables with the power socket located closer to the extreme edge, making it easier for wheelchair users to reach.

Near the library's entrance, Ms Lee has placed an "accessible collection" for people who are new to the topic of disability or people with disabilities and their caregivers.

"Particularly for autistic people, intellectual disability, the books that they require are more tailored, and it's not all over the place in our library, which can get quite overwhelming ... We wanted to put these books nearer to the entrance; if you are new to the library and you don't have much time, you can come over here," she explained.

Many parents also found the collection "very useful to start the conversation about disabilities with young children", she said.

But positioning libraries as an "equaliser" is not just about building for people with disabilities, Mr Wan said. Design has also helped Bedok Public Library's bigger pool of elderly users with the library’s catalogue services, who struggle with finding Mandarin or Tamil books without a Romanised title.

“We created this module where you can actually use your finger to write it up, then it gets translated as a search term into the system," he said.

“LOCALISED” CONCEPT FOR EVERY LIBRARY

In the future, libraries will also be seen as the “Singapore storyteller”. To do this, they should be a “significant anchor” within the community by presenting the history and culture of the area within its physical space – a function that’s carried out at the “localised level”, explained Mr Wan.

The library@chinatown, for example, is within an area with “a certain cultural and historical dimension that you cannot ignore”, he said.

This meant the library’s offerings had to focus more on “the Chinese culture and perspective” – not only in terms of the language – in order for it to work in Chinatown.

At Choa Chu Kang Public Library, reopened in October 2021 after a two-year overhaul to become a “next-generation library”, its theme of nature and sustainability is a homage to the town's farming heritage and nature parks.

Visitors are greeted by a room of lush hydroponic plants when they enter the library, while an indoor garden housing a mix of real and artificial plants sprawls across its children’s section.

Coupled with pockets of green, its reading areas that are brightly lit by panoramic windows make the library a far cry from the cramped and dingy space that this reporter remembers it to be when she frequently visited the library in secondary school about 20 years ago.

“We have feedback from patrons that this area is very spacious and … it’s still bright. It's something I'm very proud of … the study area. The spaces are quite wide and I often get compliments for giving them a lot of space rather than restricting them to a little space,” said its manager Jollene Shu.

The library has also expanded to two floors on the fourth and fifth floor of Lot One shopping mall to attract more visitors. Inspired by library@harbourfront where the adult and junior collections are separated, Ms Shu’s team placed the children’s section on the upper floor.

Not only has she received fewer complaints from readers about noise, it is more convenient for children to move from the children’s section to the shopping mall’s playground outside the library on the same floor.

While Ms Shu said the library’s demographics have shifted from having more elderly to an increase in young adults and older teenagers, she added that “whether they read a physical book or an e-book doesn't really matter to me, as long as they come and enjoy the space”.

“In Singapore, we are so limited with land and space that I feel like in this library, this is one thing that we have done well," she added.

"And when patrons come in and they see that there's this vast amount of space where they can walk around and sit around – we have kids who even lie around – that it's really very inviting. Even if they don't pick up a book from my shelves, but they are enjoying themselves … that's fine."

From Choa Chu Kang to Punggol, a library is now "about building people connections" rather than getting visitors to "passively read a book", added Ms Shu. "That's something that NLB would like to change.”

Mr Wan, whose planning and development team comprises people from various disciplines such as architecture and exhibition curation, hopes that future libraries will evoke a "sense of familiarity but also a sense of wonder" in every visitor.

“When people come in, (I want them to) know that it is still able to fulfil your basic needs, in terms of (providing) the content you’re looking for, for studying or working. Or maybe you tell me, ‘Hey, I just want a place to relax. I just want a quiet place where I can gather my thoughts, where I can be myself,'" he said.

"We want you to come in and still feel like you're at home.”