IN FOCUS: Where will Singapore's rubbish go after Semakau landfill is full?

Singapore's only landfill has 10 years left, and waste disposal rates are going up while recycling is down. The urgency to "save Semakau" or find alternatives is growing.

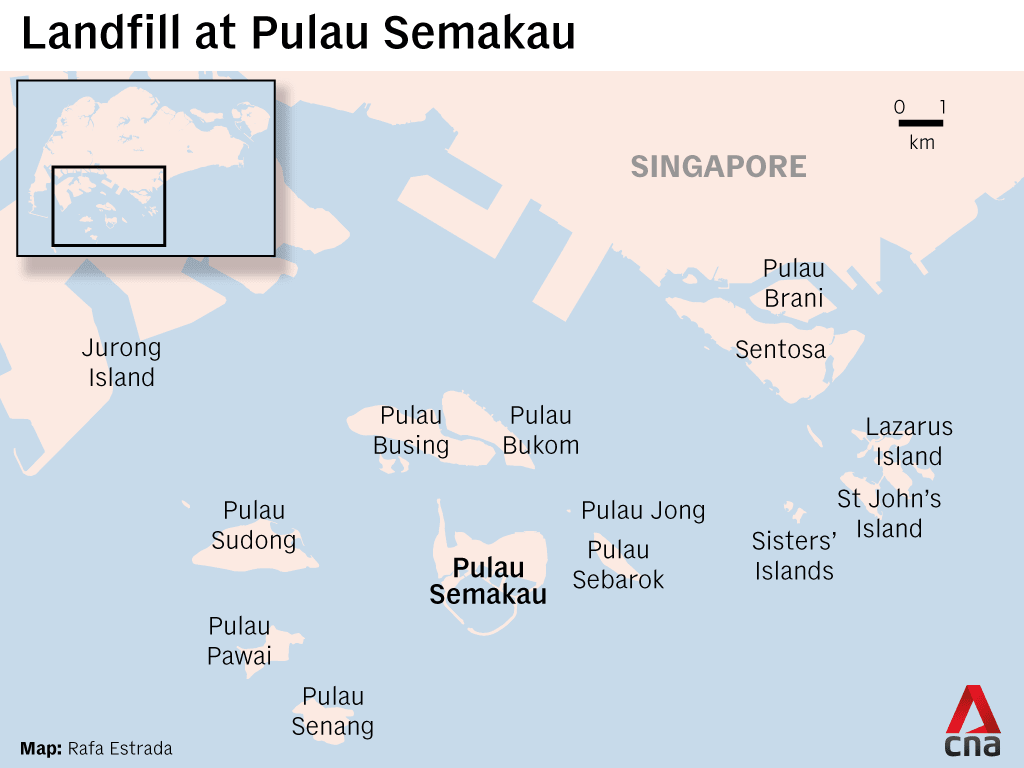

Singapore's only landfill at Pulau Semakau is more than half full and expected to reach maximum capacity by 2035. (Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: In massive rock caverns more than 100m underground, incombustible junk and ash from burning waste are buried out of sight.

A waste rationing system uses smart bins to keep track of the amount of rubbish each person throws away. People are fined if they exceed their quotas.

And in the seas south of Singapore, where the horizon used to be, rises an entirely man-made mountain of waste – Gunung Semakau.

These are some of the extreme scenarios that could happen after Singapore’s only landfill runs out of space in 10 years.

Semakau landfill is expected to be full by 2035. More than half its total capacity of 28 million cubic metres has already been used, since it opened in 1999.

“Save Semakau” has become a rallying cry for people to consume less and recycle more.

Yet statistics show that Singapore is not on track for a national waste reduction target meant to extend the landfill’s lifespan beyond 2035.

All of which points to a problem that is uniquely pressing for the nation.

“Not many other countries are so land-constrained that it would be a challenge to even find space to landfill the incineration ash,” said Mr Cheang Kok Chung, executive director of the non-governmental Singapore Environment Council (SEC).

“It’s one of those things for which, really, we have to find our own solution.”

HOW SEMAKAU CAME TO BE

Singapore used to have its landfills on the mainland. One in Lim Chu Kang became Sarimbun Recycling Park after closing in 1992.

Another, in Lorong Halus, opened in 1970 and closed in 1999. That area is now the Lorong Halus Wetland, which collects and treats water passing through the former landfill.

Semakau, located about 8km south of Singapore, then opened in 1999 as the world's first offshore landfill.

The idea was to join the two islands of Pulau Sakeng and Pulau Semakau, and turn the sea space between them into a landfill.

No one had done this before, so Singapore looked closely at how Japan built near-shore landfills as well as the United States' barging systems for offshore facilities.

In the end, a 7km perimeter rock bund was built and lined with an impermeable membrane and marine clay, to contain the waste from surrounding seawater.

The project involved moving entire villages and marine life. Some 700 coral colonies were relocated, and 400,000 mangrove saplings replanted.

The technical feat gave birth to a facility about 350ha large, or about half the size of Tengah town.

In Semakau’s first phase, it was projected to be filled by 2016. Its second phase opened in 2015, more than doubling the landfill’s capacity at the time and establishing the 2035 timeline.

Today, Semakau landfill is lauded for a surprisingly scenic and odourless environment that supports biodiversity. It is a pristine appearance that can belie the urgency of the underlying issue.

“It’s so well-maintained, so beautiful, you don’t feel like there’s a waste problem,” said Mr Lee Jek Suen, business development lead of social enterprise Green Nudge.

THE STATE OF PLAY

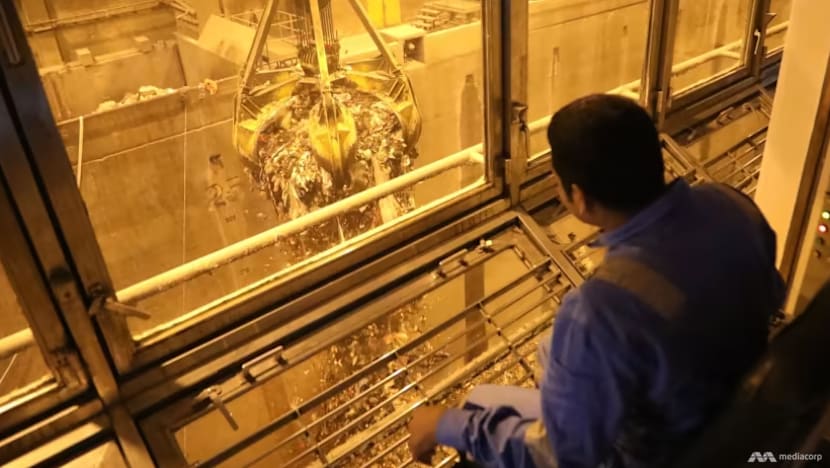

Today, trucks dump about 2,100 tonnes of waste at Semakau daily. This is made up of around 1,500 tonnes of ash and 600 tonnes of non-incinerable waste like PVC and fibreglass.

Many countries with more land do not even need to incinerate, and can landfill waste directly. That's not the case in Singapore.

Before waste is even sent to Semakau, it is incinerated to reduce it to about a tenth of its original volume.

In 2019, the government set a goal to extend Semakau’s lifespan by reducing the amount of waste sent to landfill by 30 per cent, by 2030. This is on a per capita, per day basis from a pre-pandemic baseline in 2018.

The waste-to-landfill reduction goal is paired with a target to raise the recycling rate to 70 per cent by 2030.

But earlier in 2025, Singapore's parliament heard that the amount of waste-to-landfill per capita per day “remains about the same” as the 2018 baseline. This is despite less waste being generated.

The government attributed this to lower recycling rates due to higher freight costs, import restrictions by foreign countries and lower demand for recycled materials.

This trend has played out over the past decade. Less waste is generated in Singapore now than a decade ago, but recycling has declined.

As a result, the amount of waste disposed has in fact risen - from 3 million tonnes in 2014 to 3.3 million tonnes in 2024.

CNA asked the National Environment Agency (NEA) questions on efforts to extend Semakau's lifespan; whether it has revised the 2035 timeline; and whether Singapore is considering developing other landfills.

The agency reiterated that Semakau is expected to be filled by 2035, and repeated publicly available information about recycling schemes and landfill mining studies.

Existing NEA estimates indicate that Singapore will need to build a new offshore landfill every 30 to 35 years as well as a new incineration plant every seven to 10 years, at the rate things are going.

Green Nudge’s Mr Lee said he would not be surprised if Semakau’s projected lifespan has to be brought forward from 2035, given current waste disposal rates.

Bottlenecks could even appear in the waste management system if incineration plants don't have the capacity to keep up, he said.

Singapore currently has four active incineration plants that can process a combined total of 9,710 tonnes of waste a day.

An upcoming plant at the Tuas Nexus Integrated Waste Management Facility is expected to process another 5,800 tonnes of incinerable waste a day, but the completion of its first phase has been delayed to 2027 onwards.

BIGGER, HIGHER, DEEPER, GAMECHANGER?

Sustainability experts told CNA that reclaiming more land from the sea around Semakau would seem the most intuitive way to create more landfill space.

A 2013 land use plan marked the waters between the Pulau Semakau, Pulau Jong and Pulau Sebarok islands for possible future reclamation works, if needed. But such a move would mean making trade-offs.

“Singapore’s sea space is a limited resource as well, with many competing uses, such as being the anchorage for our port," said SEC’s Mr Cheang. "Hence, we cannot assume that we can always create another Semakau after the current one is full.”

This would likely come at great cost too – S$610 million (US$474.8 million) was spent to construct Semakau in 1999, with an additional S$36 million for the 2015 expansion.

Some have also speculated if ash could be piled higher above Semakau's encircling rock bund, the same way Singapore has long maximised land use with high-rise buildings.

In 2019, then Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong joked about this at the National Day Rally.

“Our landfill is at Pulau Semakau. But that will eventually fill up, and then we will need Bukit Semakau, and then Gunung Semakau!” he said, using the Malay words for "hill" and "mountain".

Singapore will have to find a sustainable solution, Mr Lee added on a serious note.

Mr Cheang said that having a raised mound on Semakau would limit the utility of the land, as a flat plain - together with the waterfront there - better supports a wider range of industrial and even recreational uses.

Plans are already underway to explore a 60ha solar farm on the landfill, with its proximity to chemicals and energy facilities on Pulau Bukom being one of the value propositions.

Going into the realm of “pretty crazy" ideas, storing ash in underground rock caverns could be a theoretical possibility, but again an extremely expensive solution, said Mr Cheang.

Singapore uses this technology to store ammunition under the old Mandai Quarry, and crude oil under Jurong Island. The latter, which opened in 2014, cost S$950 million.

“We should do what we can now to avoid having to resort to such solutions,” said Mr Cheang.

Then there is the possibility of mining and finding other uses for the material dumped at Semakau. This could allow the landfill to be excavated and refilled.

NEA told CNA it was studying the feasibility of this, and would share more on using landfilled materials for land reclamation “in due course”.

The agency previously announced it was studying the use of materials mined from Semakau as alternative reclamation fill material for Tuas Port Phase 3.

If this works, it would be a gamechanger in giving Semakau a new lease of life, said Mr Cheang.

Another potential solution is using treated bottom ash - which is heavier and coarser - to make a construction material called NEWSand.

This can then be fashioned into concrete, lightweight aggregate and coastal protection blocks, said Associate Professor Fei Xunchang, the principal investigator of a national project to investigate the landfill and find ways to reuse its materials.

The Nanyang Technological University (NTU) engineering academic noted that high-income and coastal or island countries like Japan, Denmark and the Netherlands have established regulations and mature markets in the space of ash reuse.

But this is still in the pilot stages in Singapore. A 2020 trial used NEWSand from bottom ash to build a stretch of Tanah Merah Coast Road, for example.

Assoc Prof Fei said NTU was working with NEA to refine ash quality standards, to broaden the ways the material can be reused. This will hopefully motivate industries to accept ash as a raw material, he said.

Could treated ash, as a potential construction material, ever be produced and exported by Singapore?

Mr Remi Cesaro, executive director of the Zero Waste City consultancy, does not "expect any scenario where someone will be willing to buy it", given other countries would be dealing with their own waste.

Incineration ash could also be classified as hazardous waste under the Basel Convention, which may trigger barriers to export.

Beyond ash, municipal solid waste – everyday rubbish from homes and businesses – can also be heated to make NEWSand, at high temperatures of up to 1,600 degrees Celsius.

This technology is not widespread in Singapore yet. Conventional incinerators operate at about 850 degrees Celsius.

How one person can make a difference

Singapore’s target is to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfill by 30 per cent by 2030.

This means cutting down the amount of waste each person throws away daily, from 800g to 640g, according to the Zero Waste Masterplan.

That's 160g. Based on CNA’s weighing of common household waste, each of these sets of items weighs roughly that amount.

- Three disposable salad bowls and plastic lids

- Six plastic takeaway boxes and lids

- Eight plastic takeaway bowls and lids

- 12 plastic drink cups and straws

- 16 two-ply tissue packets

One additional tip is to ensure that waste is dry before throwing it away, says Mr Lee Jek Suen of social enterprise Green Nudge.

Wet waste is less energy-efficient to incinerate. So emptying the liquid from a drink or food container before putting it in the bin helps.

MAKE LESS WASTE

Others have imagined even more speculative futures.

In a 2023 article on Semakau’s future beyond 2035, researcher May Ee Wong and artist-researcher Juria Toramae envisioned a waste rationing scheme where smart bins track and hold people accountable for the rubbish they throw.

To the writers, the rhetoric of "saving Semakau" can be "problematic and empty" without tackling the root causes of particular forms of waste production and patterns of consumption.

“Semakau island is an external container for Singapore’s incinerated waste, even if it is seemingly put to other more productive uses,” they added.

In other words, even if Singapore finds ways to make use of landfill material, a more compelling approach would be to reduce the amount of waste to begin with.

SEC’s Mr Cheang said this goes back to the fact that waste disposal has a carbon cost, which must be managed for Singapore to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Recycling hence remains a key thrust of Singapore’s efforts to extend Semakau’s lifespan. To sustainability advocates, the challenges are clear.

Green Nudge’s Mr Lee said Singapore seems to have reached a “plateau” for recycling, due to structural reasons.

“The economics of recycling may not be quite there for every type of recyclable, especially when for certain materials, the virgin material may be cheaper than the recycled material,” he said.

“Waste is like a river, it flows downhill to the cheapest price,” said Zero Waste City’s Mr Cesaro, borrowing the words of Australian environmental consultant Mike Ritchie.

And in Singapore, that tends to lead to the landfill, as the cheaper and easier way to get rid of waste.

Some materials like metal are considered so valuable that the recovery of metal bits from ash is already part of the incineration process, Mr Cesaro pointed out. But other waste materials need more help.

NEA said it was focusing on improving recycling rates for plastics, food and paper.

It highlighted a beverage container return scheme that will be implemented in 2026, making producers responsible for the collection and recycling of their used drink containers.

“Large food waste generators will be progressively required to segregate and recycle their food waste in tandem with the completion of the integrated waste management facility,” added NEA.

But SEC’s Mr Cheang noted that households in Singapore simply have no incentive to recycle.

“Currently, a flat monthly household waste collection fee is charged, regardless of how much you dispose of, and whether you bother to recycle,” he said. “A household would have to be intrinsically motivated to do good, for it to undertake the effort of recycling properly.”

Mr Cheang said even a small financial incentive to recognise households’ recycling efforts could “turbocharge” the shift towards waste reduction.

Already, some town councils have set aside space for smart recycling bins that give out reward points to residents who use them, he noted.

One local company, SG Recycle, offers three cents for every kilogram of paper deposited in machines around Singapore.

Public waste collectors have also rolled out cash-for-trash recycling stations in estates. Cora Environment offers five cents for every kilogram of carton and other papers, and 50 cents for a kilogram of aluminum cans, for example.

Otherwise, it's the ubiquitous blue bins set up to collect recyclables - where contamination is a well-documented hindrance.

Recycling rates for paper - the material most at risk of contamination - have dropped steeply in the past decade, from 52 per cent to 32 per cent.

Mr Cheang suggested having a dedicated collection bin just for paper in addition to the blue recycling bin, noting that this would be an easier transition than switching fully to an array of bins for different materials.

When it comes to food waste, one solution that researchers at the National University of Singapore and Singapore-ETH Centre are studying is the use of black soldier fly larvae, in a project funded by the National Research Foundation.

Compared to composting, which needs more space and does not capture the high-level nutrients in food scraps, black soldier flies are a more efficient method of breaking down food waste, said Ms Niraly Mangal, doctoral researcher at Singapore-ETH Centre.

Some obstacles to wider adoption are the “ick factor” attached to insects and waste, and the NIMBY or "not in my back yard" attitude when it comes to where black soldier fly facilities could be located in neighbourhoods, said Ms Mangal.

Like so many other pieces of the puzzle that is Singapore’s waste disposal problem, implementing such a solution will involve changing mindsets.

But if successful, a different scenario could await Singapore beyond 2035, absent a summit of rubbish on the skyline or punitive measures for producing too much trash.

Imagine a resident dropping off clean, dry recyclables at a smart machine at his void deck, earning reward points to redeem for grocery vouchers.

He then takes a short walk to his estate’s shared black soldier fly facility, and empties food scraps and unwanted leftovers there. Trained volunteers will later harvest and process the high-protein larvae to feed fish in community ponds and fertilise community gardens.

Out at sea, mangroves and corals thrive in the waters off Pulau Semakau – still Singapore’s only landfill, and where lately, the dump trucks have been quiet.