Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is straining from climate change but ‘controversial’ research could help save it

Aerial surveys are used to assess bleaching damage to the reefs. (Photo: CNA/Jack Board)

TOWNSVILLE, Australia: Under bright lights and close scrutiny from leading scientists, young corals are taking shape. These are the new breed, the lab rats and the hybrids, being exposed to a wide range of different water conditions.

Some experience extra heat or more light, water contaminants and changes in salinity. Three million litres of seawater can be pumped through this system every day. While the natural environment outside has never been more unpredictable, here, everything is controlled.

In close proximity to one of the world’s most precious ecosystems, there is cutting edge science.

This is the National Sea Simulator, a world-class facility that is being used by researchers at the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in the state of Queensland to better understand how climate change is impacting corals across the Great Barrier Reef.

What happens here could profoundly shape the reef’s future.

Reefs are in a steep decline right across the globe. Corals are dying as global carbon emissions continue to push up temperatures. Marine heatwaves are becoming increasingly frequent, leading to mass bleaching, events where stressed corals lose their colour, leaving reefs to resemble eerie white bone yards.

The Great Barrier Reef is the world’s largest, spanning an area larger than Malaysia, stretching from southeast Queensland to the tip of Papua New Guinea. It is diverse, complex and made up of thousands of different islands and reefs that have evolved over millennia.

Yet, never has its survival been more imperilled.

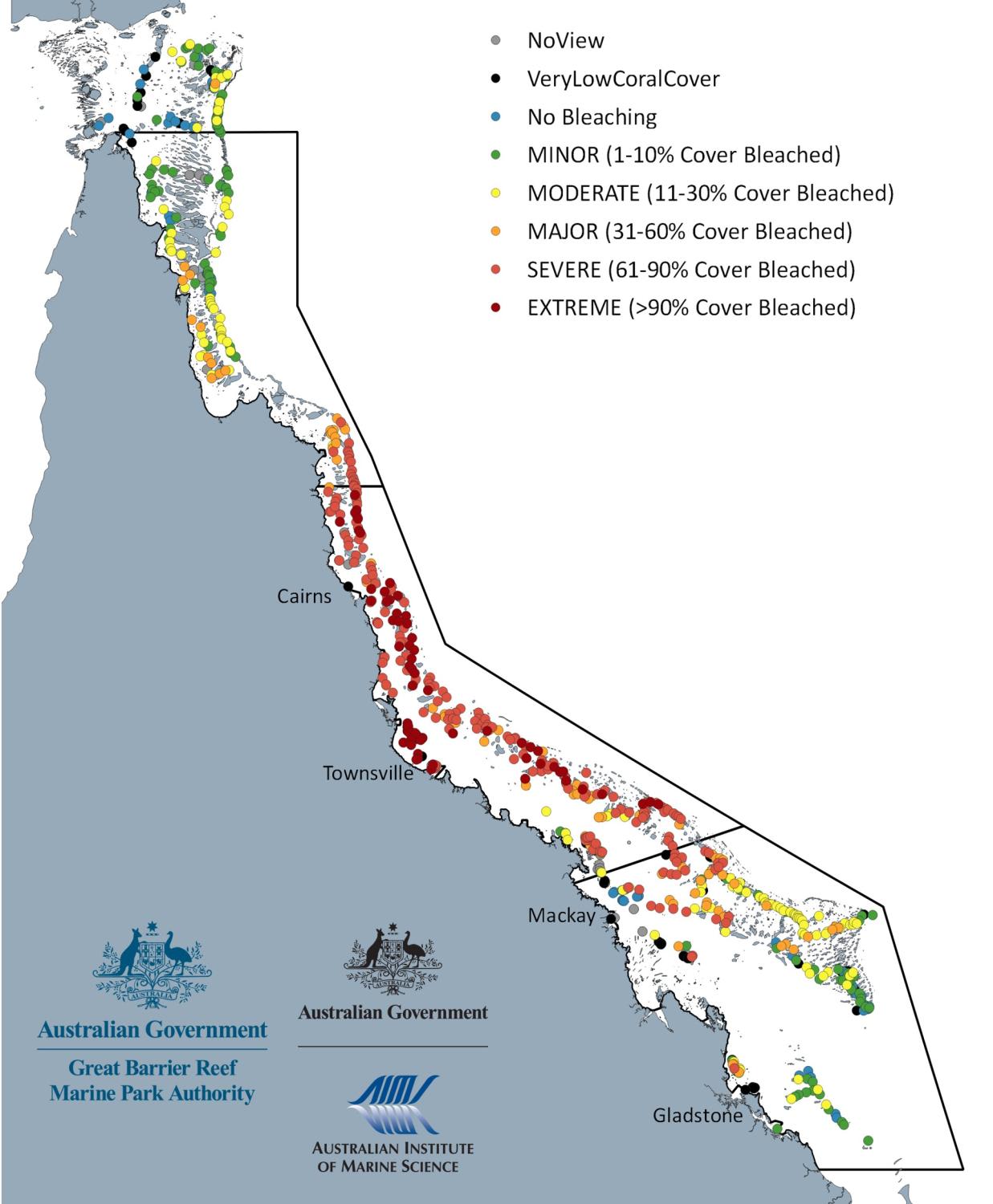

After a period of delay, this month, government scientists confirmed that 91 per cent of surveyed reefs had bleached this Australian summer.

It was the fourth mass bleaching event that the reef has experienced since 2016. More alarmingly, this is the first time major coal damage has occurred during a La Nina period, which is associated with cooler temperatures and more cloud cover.

“The long term outlook for the reef is not great, unfortunately. And the main reason is climate change,” said Dr Paul Hardisty, the chief executive officer of AIMS, which is the country’s tropical marine research agency.

“If we keep putting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas gases into the atmosphere at the rate we're doing now, then certainly by the end of this century … it is very unlikely that reefs as we know them today will survive, he said.

The Australian government's Reef Restoration and Adaptation Programme, which is managed by AIMS, is a hugely ambitious plan to alter that trajectory.

It is a multi-pronged approach involving direct intervention on the reef. Think genetics, engineering, restoration, breeding and innovative technologies rolled out, potentially, on an entire ecosystem-scale.

“We're trying to make sure that the reef gets a fighting chance. So that while we bring emissions down, which is absolutely critical, we find ways to help the reef become more resilient and adapt to warming waters,” Hardisty said.

“We're not talking about some of the small coral gardening efforts that are happening around the world where divers go down and try to regenerate by hand small areas of reef that have been degraded. It’s an automated, major, almost industrial-scale effort to help the reef adapt to climate change.”

The interventions primarily include cooling and shading the reef - a defensive action against climate change driven warming - restoring damaged and degraded reefs and helping corals to evolve and adapt to more harsh environmental conditions.

The latter component is what Dr Carly Randall is focused on at AIMS through her coral seeding research.

The idea is to identify what genetic traits are allowing certain members of the same coral species to survive during bleaching events. Through experimentation, it is hoped that natural adaptation among corals can be rapidly accelerated.

More resilient larvae, spawned in the simulator, can then be placed onto custom-designed devices and installed in the wild in specific, ideal locations. Corals that would otherwise have a tiny chance of survival will be bred to thrive instead.

The concept is in its early days, but the team has grand plans.

“We're looking at state-of-the-art technology and equipment that we can use to develop systems that we can scale up to production of hundreds of thousands to millions of corals a year. We're looking at implementing these in an aquaculture setting so that we can really mass-produce corals at a rapid rate to be able to supply an ecosystem so large,” Randall said.

“It's certainly a challenge. But the alternative is we don't do anything. What we're trying to do is push the envelope.

“But it is clear that we have to combat climate change at its root for these interventions to be successful in the future. They have to go hand in hand. We can't just restore the reef and let greenhouse gas emissions go through the roof,” she said.

ALIVE BUT JUST HOLDING ON

Among experts, there is no consensus on the merits of the direct intervention method.

One of the world’s leading coral scientists, Terry Hughes, believes the approach is “controversial” and risks putting technology in the driving seat to save the reef from climate change, instead of fundamental policy shifts.

He is also wary of meddling with ecosystems to the extent that natural balances can be upset, raising a lesson from the past when the cane toad was introduced to Queensland in the 1930s as a form of biological control, only to become a pest itself.

For Hughes, the latest bleaching event is evidence that reefs - despite their innate evolved capacity to recover from shocks, like temperature rise and cyclones - are not adapting fast enough to climate change.

But for them to stand a chance, he says that stabilising global temperatures must be the most urgent priority.

“The corals are used to a level of disruption or disturbance. But they have not evolved to cope with mass mortality every two or three years, which is what we're seeing now. Those gaps are nowhere long enough for a proper recovery to take place,” Hughes said.

“The climate modellers tell us that by mid-century, if not earlier, the temperatures will be high enough to trigger mass coral bleaching every consecutive summer. And if we get to that outcome, then it's pretty much game over for the Great Barrier Reef as we see it today.”

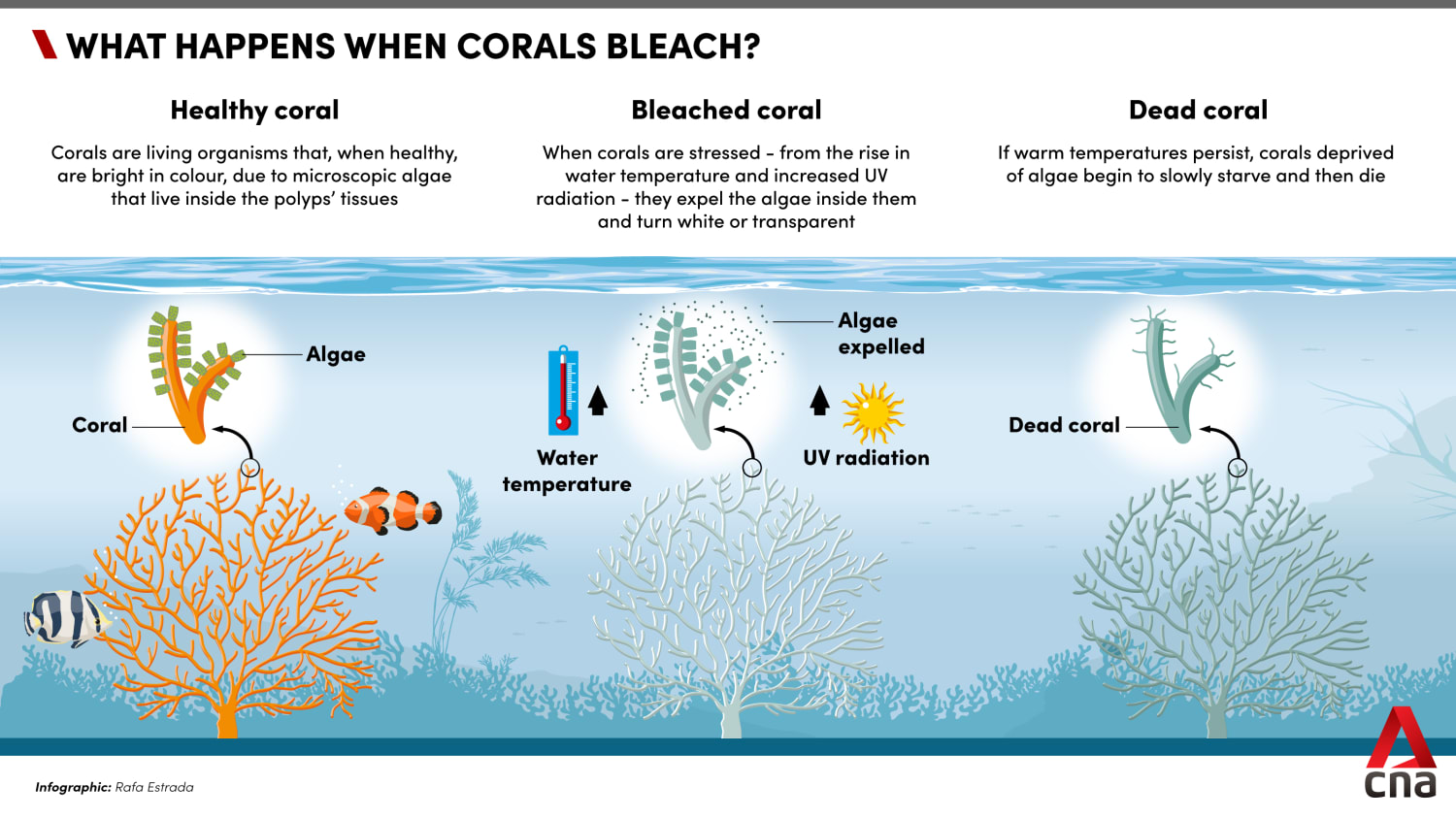

Bleaching happens when corals start to expel the photosynthetic algae that live inside them. The algae normally gives them their bright colours and food supply. Once the distressed corals have turned white, if warm temperatures persist, they can then die.

Having this damaging situation during a La Nina cycle is particularly alarming. However, bleaching is not a death sentence and corals can rebound given the right conditions.

“We're still learning about what's happening out there. The bleaching itself is extremely variable. Bleached coral is still alive and if the temperature moderates soon enough, then corals can recover, which is obviously what we're hoping for,” said David Wachenfeld, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority’s chief scientist.

“In the long run, the future of the Great Barrier Reef is most critically dependent upon the future of climate change. And that means that we need the fastest and strongest possible global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“Now, as a marine park management agency, we can't deliver that. But it is very much our job to educate the people of the world that no matter where you live, your actions and your greenhouse gas emissions and reducing them will play an important role in protecting the future of the Great Barrier Reef,” he said.

Academics believe that collective knowledge about the reef is insufficient to truly understand what climate change is causing.

“There are still really critical areas of fundamental science that's missing. And so, we don't know that much about the bleaching phenomenon. We don't know the genes that control it. We don't know how inheritable those genes are,” said Andrew Baird, a professor at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University.

“So every time another event comes on, no one is prepared for it. Without doing the detailed, manipulative, experimental work in the water, we're not learning anything. So it's just a staggering loss of opportunity to really get to the bottom and understand this process.”

These are some of the information gaps that AIMS is hoping to discover through its interventionist programme.

What is discovered has implications beyond Australian waters. Indeed, the entire world, including vast reefs in Southeast Asia, are feeling the heat.

A REGIONAL AND GLOBAL CRISIS

With reefs supporting a quarter of the entire world’s marine life, their loss and damage would have major environmental and economic impacts.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated in a major report this year that the degradation of reefs could directly affect the livelihoods of about 4.5 million people in southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean region alone.

It forecast that a 2 degrees Celsius rise in ocean temperatures will eliminate most reef systems.

Already, sea temperatures surrounding the coastal areas of the Coral Triangle, a critical ecosystem spanning Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Timor Leste and Solomon Islands, are rising approximately 0.1 degrees every year and could be 1.4 degrees warmer by the end of the century.

“Typically, many reefs around the world, in places like Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines have bleached four or five or six times - a few have bleached eight or more times - since the 1980s. So they're all experiencing this very changed dynamic where there's a huge loss of coral populations every few years,” Hughes said.

“Coral reefs are sometimes called the canary in the coal mine, the implication being that they're more vulnerable than other ecosystems and sort of a harbinger of what could happen to more robust ecosystems in the future. I don't really buy that terminology. I think they're more like the poster child,” he said.

Hardisty of AIMS said intensive study of the Great Barrier Reef - as the world’s largest reef system and “probably the most resilient and one of the most biodiverse” - is crucial to then apply in other parts of the world too.

“If it's struggling, then, you know, other reefs around the world are going to be struggling too,” he said.

“So when you talk about Southeast Asia and the greater Pacific, a lot of our work is actually looking at how we translate what we learnt, and the technologies that we're developing, into those parts of the world.”

GETTING PEOPLE TO CARE

Visiting the Great Barrier Reef during the late summer and spring was to experience a wilder side to its beauty. Conditions were rough, sea swells challenging for tourist boats and strong winds reducing visibility for divers and snorkellers.

The Great Barrier Reef is still a magical place - green sea turtles bobbed on the sea surface, while underneath colourful giant clams sat alongside delicate anemones, home to families of clown fish.

But it was clear that it was not at its best, with the reef exhibiting a muted version of its former glory.

Yet, not everybody involved in the tourism industry seemed concerned about the conditions, short or long term.

“I’m a bit sceptical about all that,” a tourist boat operator, who declined to be named, told CNA when asked about the threat of climate change. “I’ve been coming out here for 20 years and it’s still as beautiful now as it was then.”

The science disagrees with this sentiment, and while across vast numbers of reefs there are areas less affected by rising temperatures, the system as a whole is struggling.

It prompted scientists from UNESCO to last year recommend that the reef be placed on a list of world heritage sites “in danger” due to climate impacts and slow progress on improving water quality.

Intensive lobbying efforts from the Australian government in response meant the recommendation was not enacted but another meeting in June is expected to take in more recent information and data from the latest bleaching event.

Meantime, tourist numbers to the Queensland coast have been decimated in recent years by a combination of seasonal flooding, the COVID-19 pandemic and this season’s weather conditions.

In Townsville, Paul Crocombe, the director of Adrenalin Snorkel and Dive, believes the reef’s prospects as an ecosystem and an attraction remain bright, but only if climate change action is taken more seriously.

Local communities across the state are dependent on that happening.

“When people come to the area, they not only come out to the reef and support the marine tourism industry. It's also the accommodation, restaurants, supermarkets and chemists. And so the income from tourism is really important to the area and it does reach quite a long way,” he said.

“If we want to keep a good healthy reef looking like this, we're going to have to be really serious about getting climate change under control and keeping the sea surface temperature down.

“It’s still going to be there in 50 years. It’ll last for sure. But it may be quite different if we don't look after the environment. You will see a change on the reef,” Crocombe said.

Getting grassroot involvement and awareness about the plight of the reef has been a mission for volunteers at Reef Check, an international organisation that has groups working in local chapters in strategic reef areas.

There is a need to monitor changes to fill important gaps in knowledge about how the reef is coping, according to Jenni Calcroft, a Great Barrier Reef Project Coordinator in Townsville.

Sending divers out to reef sites on a semi-regular basis to conduct surveys is helping with that goal.

“To get people to care and to lobby their government and to make changes to those really big policies, you need the people. And if the people don't understand what's going on, then that's never going to happen. You have to inspire people and give them something to believe and hope for,” Calcroft said.

“We rely on the ecosystem and coral reefs for so many different kinds of benefits. And it's also absolutely gorgeous. So if we don't start to make changes at a smaller scale, and then on a larger community scale, we're going to lose a lot of those benefits that coral reefs provide us.

“I think it's important to just acknowledge that, yes, there is a problem,” she said. “But it's not something that we can't do something about.”