IN FOCUS: Is Southeast Asia losing the battle against dengue?

Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia have unleashed special mosquitoes injected with bacteria along with a slew of community efforts to tackle dengue. But with cases still on the rise, just how effective are these measures?

.png?itok=ktophAxE)

Southeast Asian countries Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia have in recent years been plagued by a spike in dengue cases. (Illustration: CNA/Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE/KUALA LUMPUR/JAKARTA: When Benjamin Loh came down with a fever of 40 degrees Celsius last July, he thought he had caught COVID-19 again.

That wasn't the case, so the 36-year-old Singaporean went to a general practitioner, who suspected dengue and recommended a blood test.

Mr Loh, an entrepreneur and professional speaker, soon received a text message from the doctor, saying: "You better go to the hospital."

His platelet count was 20,000 per microlitre of blood. Normal levels range between 150,000 and 450,000 for platelets, which help blood clot and prevent excessive bleeding.

Getting cut would lead to a life-and-death situation, the GP warned.

Mr Loh ended up hospitalised with dengue for almost a week, an episode he described as a “curse from an ex-lover”. The father of one battled body aches, nausea and high fever; and struggled to even muster the energy to reply to emails.

“It was this whole potpourri, this whole medley of symptoms that really make you want to not do anything.”

Jakarta resident Patricia Tambunan had it worse: Her stay in hospital was more than seven days, and the virus made the 28-year-old so nauseous that she vomited every time she ate or drank.

Mr Loh and Ms Tambunan are among tens of thousands of people across Southeast Asia who've been infected with dengue recently, with hundreds dying.

Governments in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia specifically have implemented measures such as bacteria-carrying mosquitoes and community campaigns, to name a few. But are they working? CNA takes a closer look at the three countries’ battle against the virus.

WHY IS DENGUE SUCH A CONCERN?

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes dengue as a viral infection caused by the dengue virus (DENV), transmitted to humans through the bite of infected mosquitoes - specifically Aedes mosquitoes.

Dengue is found in tropical and sub-tropical climates worldwide, and mostly in urban and semi-urban areas.

There are four different serotypes of dengue virus (DENV1 to 4) circulating in the world. While many DENV infections are asymptomatic or produce only mild illness, the virus can occasionally cause more severe cases and even death.

In recent years, dengue has made its way to places that have never had it, including France, Italy and Chad. Late last year, two people in the Southern California region came down with dengue fever without travelling outside the United States, where the mosquito-borne illness is rare.

South American nation Brazil has been in the spotlight as well, after reporting more than a million cases and around 300 deaths in the first two months of the year. Several states have declared a state of emergency.

Southeast Asia, meanwhile, has long been a victim of dengue.

In February, with dengue cases steadily spiking over the weeks, Singapore’s National Environment Agency (NEA) urged "immediate action" to suppress Aedes mosquito numbers.

An overall upward trajectory can be traced back to 2018. Then, Singapore reported over 3,000 cases - an almost 20 per cent increase from 2017, when infections had fallen to a record 16-year low.

Cases continued to climb to nearly 16,000 in 2019, before skyrocketing to a record of over 35,000 and 32 deaths in 2020.

A significant drop to over 5,000 cases was recorded in 2021, with NEA saying at the time that this was likely due to temporary immunity from the large outbreak of the previous two years.

But the total number of cases shot up again to more than 32,000 in 2022. There were also 19 deaths reported.

Last year, based on quarterly data, there were 9,950 cases and six deaths in total.

Singapore's cumulative number of dengue cases for 2024 already stands at 4,817, for the week ending on Mar 23.

Neighbouring Malaysia logged over 123,000 dengue cases in 2023, an 86 per cent increase from about 66,000 cases the year before. The numbers in 2022 were, in turn, more than double the more than 26,000 cases reported in 2021.

There were a total of 100 dengue-related deaths last year, also nearly double the 56 in 2022.

As of Mar 16, Malaysia has seen 38,524 dengue cases and 24 deaths.

Over in Indonesia, there were nearly 18,000 cases in January alone - up from about 12,500 in Jan 2023.

The country has recorded more than 21,000 cases and at least 191 deaths as of early-March. In its most populous province of West Java, the Cianjur regency was placed on alert earlier this month, with local government officials warning of an emergency status if cases don't come down.

WHAT'S TO BLAME?

The dengue surge in the archipelago is due to several factors including the El Nino weather phenomenon, which results in hotter weather, experts said.

“Mosquitoes mature faster, lay eggs faster. The eggs hatch faster and the number of mosquito bites to humans also increases,” explained Dr Riris Andono Ahmad, a researcher at Gadjah Mada University’s Centre for Tropical Medicine.

The rainy season, coupled with El Nino, also leads to the formation of stagnant puddles. These become breeding grounds for Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae, said Dr Riris.

Warmer weather - up to a certain point - also shortens the incubation period of the dengue virus within the mosquito, explained Singapore-based professor Hsu Li Yang.

The vice dean of global health and programme leader of infectious diseases at the NUS Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health added that the role played by climate change has not been “well studied”.

In Malaysia, the rise in dengue cases is due to climate change, rapid urbanisation as well as improper waste management and water storage that give Aedes mosquitoes a chance to breed, said the country's health minister Dzulkefly Ahmad.

Increasing population density in built-up areas doesn’t help either, creating more breeding and biting opportunities for the Aedes aegypti.

Dr Borame Sue Lee Dickens from NUS’ Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health pointed out that Aedes aegypti can survive and adapt within urban cities.

“The mosquitoes can breed in as little as a teaspoon of water,” she said, thus making dengue “remarkably difficult” to control.

Another area of concern is immunity to the dengue virus.

Singapore, for one, made dengue fever a notifiable disease in 1977. This is when a disease is of public interest due to its contagiousness, severity or frequency and health providers are required by law to report to public health officials.

At the time, adults who had grown up in the 1950s and 1960s had already caught dengue in their childhood and were hence immune to the virus.

But the suppression of the mosquito population thereafter meant that later generations did not get infected with dengue.

“What happened over time is that more and more of our population is now remaining vulnerable to dengue well into adulthood,” said Professor Ooi Eng Eong with the Emerging Infectious Diseases Research programme at Duke-NUS Medical School.

If population immunity is low, more would need to be done to control the mosquitoes, he added.

”Unless you get to the level of possibly close to elimination or even elimination, we're not going to solve the dengue problem in Singapore.”

Prof Ooi also pointed to a link between socioeconomic variables and dengue incidence in Singapore.

For instance, there are those who can afford to spend more time in air-conditioned rooms which mosquitoes “do not like so much”, while others live in conditions more favourable for mosquitoes to bite and transmit the virus.

And those who cannot afford healthcare will choose to delay seeking medical attention, versus those who may seek help earlier and therefore start disease management earlier as well - though this is not unique to dengue, Prof Ooi stressed.

WHAT'S BEING DONE ABOUT IT?

With dengue endemic in Singapore for more than 50 years, vector control measures have long been in place to attempt to reduce infections.

Project Wolbachia - one of Singapore's key efforts - kicked off in 2016, with NEA releasing in parts of the country male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes carrying the Wolbachia bacteria.

When these males mate with female urban Aedes aegypti mosquitoes without Wolbachia, their resultant eggs do not hatch.

Over in Indonesia, six cities - Bontang, Kupang, Semarang, West Jakarta, Bandung and Denpasar - will also deploy Wolbachia mosquitoes, state news agency Antara reported this month.

Aside from such scientific methods, traditional prevention strategies remain key, said Indonesia’s Dr Riris.

These span emptying water containers, closing water storage areas, rearing fish to gobble up mosquito larvae, community clean-ups and using mosquito repellent.

In Indonesia, vector surveillance is done by individuals called jumantik officers, who are appointed by local governments, said health ministry spokesperson Siti Nadia Tarmizi. They make their rounds from house to house, typically on Fridays, to check for mosquito larvae and are paid about IDR550,000 (US$35) per month, according to news outlet Kompas.

These efforts must be carried out on a large scale to have an impact, noted Dr Riris.

Meanwhile, for Malaysia, apart from prevention, surveillance and community involvement, the government is also collaborating with a non-profit drug research and development organisation - to conduct clinical trials of several repurposed drug candidates for dengue.

These include drugs that have been used to treat Hepatitis C, among others. The aim is to bring “cost-effective and accessible treatment to fruition within the next five years”, said Dr Dzulkefly, the health minister.

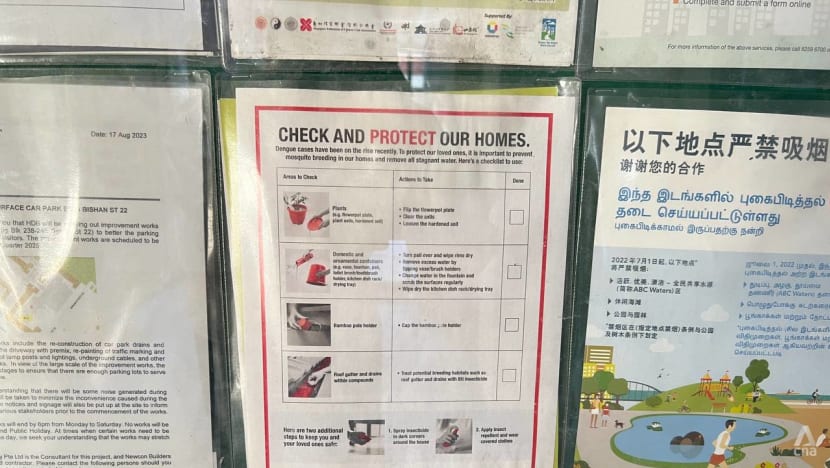

Singapore has in addition invested in various educational campaigns over the years, in a bid to raise public awareness of dengue.

It started with a “Keep Singapore Clean and Mosquito Free” movement in 1969 and has morphed into an annual National Dengue Prevention Campaign.

This rallies the community to try and stop dengue transmission from surging ahead of the traditional peak period from June to October, explained Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu, in a written reply to a parliamentary question in 2022.

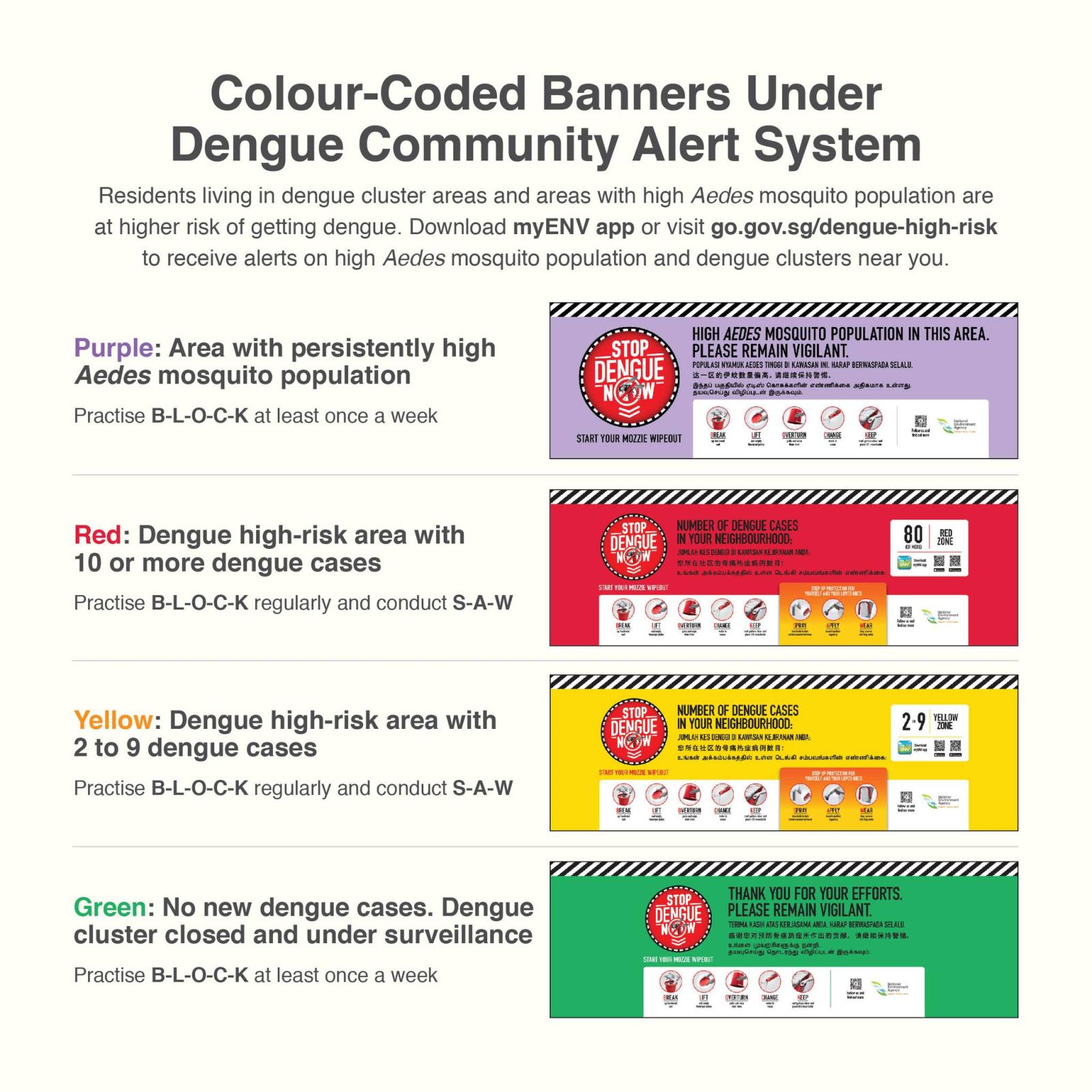

NEA also has a Dengue Community Alert System where colour-coded banners inform residents about the risk level in their locality. In 2022, the agency launched a new purple banner for areas with persistently high Aedes aegypti mosquito population.

Control and preventive measures aside, a vaccine for the dengue virus was also approved for use in Singapore in 2016.

Developed by French pharmaceutical company Sanofi Pasteur, the Dengvaxia vaccine - for individuals aged 12 to 45 years - is the only licensed dengue vaccine in the country.

It requires three doses to be administered over 12 months by injection, and is effective for up to four years after the third dose. Those outside of the approved age group but who want to be vaccinated will have to seek a doctor’s advice, the Health Sciences Authority (HSA) said back then.

The vaccine also has its limits; it is not recommended for those without prior dengue infection.

In 2012, Singapore also expanded its dengue virus surveillance into a cross-border system, setting up together with Malaysian health authorities and Indonesian academics the United In Tackling Epidemic Dengue network to also share information and knowledge.

"This network has been effective in aiding Singapore’s fight against dengue by providing situational awareness on dengue in neighbouring and regional countries," NEA told CNA.

Given Singapore’s status as a trade and travel hub, the cross-border sharing of data has been useful in identifying common virus lineages in the region and their association with outbreaks in respective countries, the agency added.

HOW EFFECTIVE ARE THESE MEASURES?

When asked in February about the effectiveness of Project Wolbachia, Ms Fu, the minister, said four sites had achieved more than 90 per cent reduction of the local Aedes aegypti mosquito population.

Data from 2019 to 2022 also indicated that residents living in areas with at least one year of Wolbachia releases were up to 77 per cent less likely to be infected with dengue, she added.

NEA is set to expand Project Wolbachia to five additional residential areas in the first quarter of this year. With this, 35 per cent of all households in Singapore will be covered.

Malaysia, meanwhile, has released Wolbachia mosquitoes in 32 localities across seven states since 2019. Dengue cases declined by 45 to 100 per cent in 19 of these localities.

The government in January said it plans to release Wolbachia mosquitoes in another 10 localities.

For Indonesia, however, lack of information and the spread of falsehoods have hampered the rollout of Wolbachia mosquitoes, such as in Bali late last year.

On social media, fake claims circulated about the mosquitoes transmitting Japanese encephalitis (a mosquito-borne virus that can cause severe illness) or “LGBT genes”; as well as them being part of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates' “depopulation plan”.

Such misinformation is not present in Singapore, where the challenge lies instead in keeping the dengue issue top of mind.

“Singaporeans are generally aware of the risk of dengue but it is difficult to constantly remember to check for mosquito breeding in the home,” said Dr Dickens.

Duke-NUS’ Prof Ooi said that for people in Singapore, knowledge “hasn’t always translated to action”.

“Sometimes the thinking is that ... public health authorities should be taking care of this problem."

Mr Loh, the Singaporean who had a brush with dengue, in fact caught the virus around the same time his residential area in Toa Payoh was identified as a cluster in late June 2023.

But he was “quite oblivious” to it being a hotspot, he told CNA. “You don't think that anything will hit you until it really hits you.”

Post-dengue, Mr Loh and his wife ensure their three-year-old son sports two different types of mosquito repellent stickers when going to the playground. Mr Loh himself has started using insect repellent before heading out.

He stops short of going to the extent of only dressing in long pants and long-sleeved shirts.

“It'll be crazy in this ‘sauna’ Singapore ... Having the middle ground of precaution, self-care and as well as not being too paranoid does help.”

WHAT COULD BE DONE BETTER?

NUS' Prof Hsu noted that Singapore's "clearly successful" initial execution of Project Wolbachia has been presented to the international academic community.

The initiative will need to be scaled up considerably before having an impact on national dengue rates, he said, adding that the programme is also designed such that recurrent releases of the mosquitoes are needed for long-term suppression of dengue.

“Even if these releases are just directed at dengue ‘hotspots’ - as might be a strategy for the future - this will be costly and long-term sustainability might be an issue, as there is no clear ‘exit strategy’ short of newer technology,” Prof Hsu added.

He pointed out that more effective and safer vaccines would be key.

Municipal and housing designs that minimise mosquito breeding will also be useful, Prof Hsu said, pointing to artificial intelligence (AI) as a tool to co-design such innovations.

In various parts of the world, AI is already gradually being tapped as a tool to fight dengue.

Humanitarian aid organisation UNICEF's innovation and climate teams are working with partners to create AI models to predict and prevent future outbreaks.

In Singapore, security firm Certis debuted AI technology in 2020 that may someday predict dengue hotspots before they emerge.

Prof Hsu pointed to Indonesia's Yogyakarta as a success story in dengue control. The city’s strategy involves replacing the native mosquito population with Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes that are inherently more resistant to the dengue virus.

A study subsequently showed a 77 per cent reduction in cases and 86 per cent reduction in hospitalisations in Wolbachia-treated areas compared with untreated ones.

Singapore, too, is arguably a good example of how to suppress dengue with extensive vector control campaigns and use of Wolbachia, said NUS’ Dr Dickens.

Experts noted that as a disease that occurs in cycles, "success" in dealing with dengue can change and evolve as countries register fewer cases for a period and then suddenly see surges with new serotypes reported.

"Each country ... is facing their own challenges in controlling dengue, that often extend outside of public health," said Dr Dickens.

Healthcare budgets face significant pressure when funding is needed for new housing, social welfare, building of new infrastructure among other national priorities.

"For countries that are experiencing civil unrest or carrying out disaster mitigation from events such as natural disasters, dengue control may not be an immediate priority, which can cause dengue burdens to rise," added Dr Dickens.

“So success is relative."