IN FOCUS: Awash with billions in Big Tech money, but Southeast Asia’s cloud and AI boom faces limits

Billions of dollars in AI and cloud infrastructure investments have poured into Southeast Asia. Now, the region has to plug its digital skills gap, tackle the industry’s carbon footprint and come up with a rulebook.

STT Bangkok 1 - a large-scale data centre belonging to STT GDC - operating in a suburb of the Thai capital. (Photo: STT GDC)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BANGKOK: It takes the press of a button for the secret room to be revealed. A solid wall slides open, revealing the innards of a data centre through an expansive glass pane.

Rows and rows of black cages, humming with sound and lights blinking inside, stretch into the distance. These are the network racks of the new industries driving a digital transformation.

This is a high-security zone, carefully temperature-controlled and monitored by a team around the clock. Even staff members need permission from their clients to enter the data floor.

The hyperscalers are all here – the cloud providers, big data, digital services, game makers and artificial intelligence (AI) pioneers; operators that need vast computing resources, automation and efficiency.

From the outside, this facility – dubbed STT Bangkok 1 – stands out in the neighbourhood. With its futuristic cladding and high security perimeter, it is conspicuous among residential apartments and small factories.

It is part of the suite of data options installed by Singaporean outfit ST Telemedia Global Data Centres (STT GDC), a fast-growing operation that owns and operates around 95 data centres in 11 countries.

Firms from around the world are pouring billions of dollars into buildings like this in Southeast Asia, forming part of a new digital infrastructure landscape across the region.

The tech rush is here.

“Southeast Asia is one of the hottest markets. We're seeing massive investments come in and it doesn't look like it's stopping,” said Lionel Yeo, chief executive officer of STT GDC Southeast Asia.

Multiple factors are driving the growth of data centres.

On the back of rapid AI development and the need for cloud computing, the demand for data centres is growing by up to 20 per cent annually to 2028 across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region, according to Maybank Investment Bank.

AI requires far more computing power than traditional tasks. Generative AI systems – which include large language models like ChatGPT – can use up to 33 times more energy than regular processes without AI.

Globally, the demand for AI services is surging – computational needs are doubling every 100 days, according to 2023 data by Chinese researchers.

Based on the Microsoft and LinkedIn Work Trend Index, 88 per cent of knowledge workers in Southeast Asia already use generative AI.

At the same time, the region is witnessing deep demographic shifts that are coinciding with a regional charge towards digitalisation.

In recent years, some 125,000 new internet users have been coming online daily in the region, and individual demands for monthly data in South and Southeast Asia are forecast to increase more than threefold by 2025 compared to 2019, according to Deloitte.

The rise of the middle class, and the growth of populations eager to embrace technology are major factors in the data drive, said Vu Minh Khuong, an associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) at the National University of Singapore who focuses on economic development and policy analysis.

The value of Southeast Asia’s digital economy is predicted to triple to US$1 trillion by 2030, a figure that could then double with the right policies, according to research by Boston Consulting Group.

Digital infrastructure to support the growth of e-commerce platforms, online services, video streaming and social networks will be necessary, Yeo said.

There is no shortage of providers looking to edge their way into the region, going by the flurry of announcements by the world’s most influential tech companies this year.

That is raising new types of challenges for all involved, from those regulating AI, to the education sector preparing digital-ready workforces and the corporations themselves under pressure to clean up their carbon footprints.

THE MONEY IS FLOWING

A certain level of jostling is underway between these international giants in a landscape that is about to see a consolidated level of demand for digital services and infrastructure, analysts said.

“A lot of opportunities are there in Southeast Asia for the big digital companies, especially from the digitalisation transformation perspective,” said Juan Kanggrawan, a Jakarta-based digital expert with experience in the public and private sector.

“It’s not only the US or European companies but also Chinese companies and those from the Middle East, Japan and so on that want to push further into Southeast Asia,” he said.

The broader regional market is still underserved by available data capacity, according to Maybank analysis, which found the region 55 to 70 per cent underpenetrated in data centre supply compared to the likes of China, South Korea and Japan, which are more developed markets.

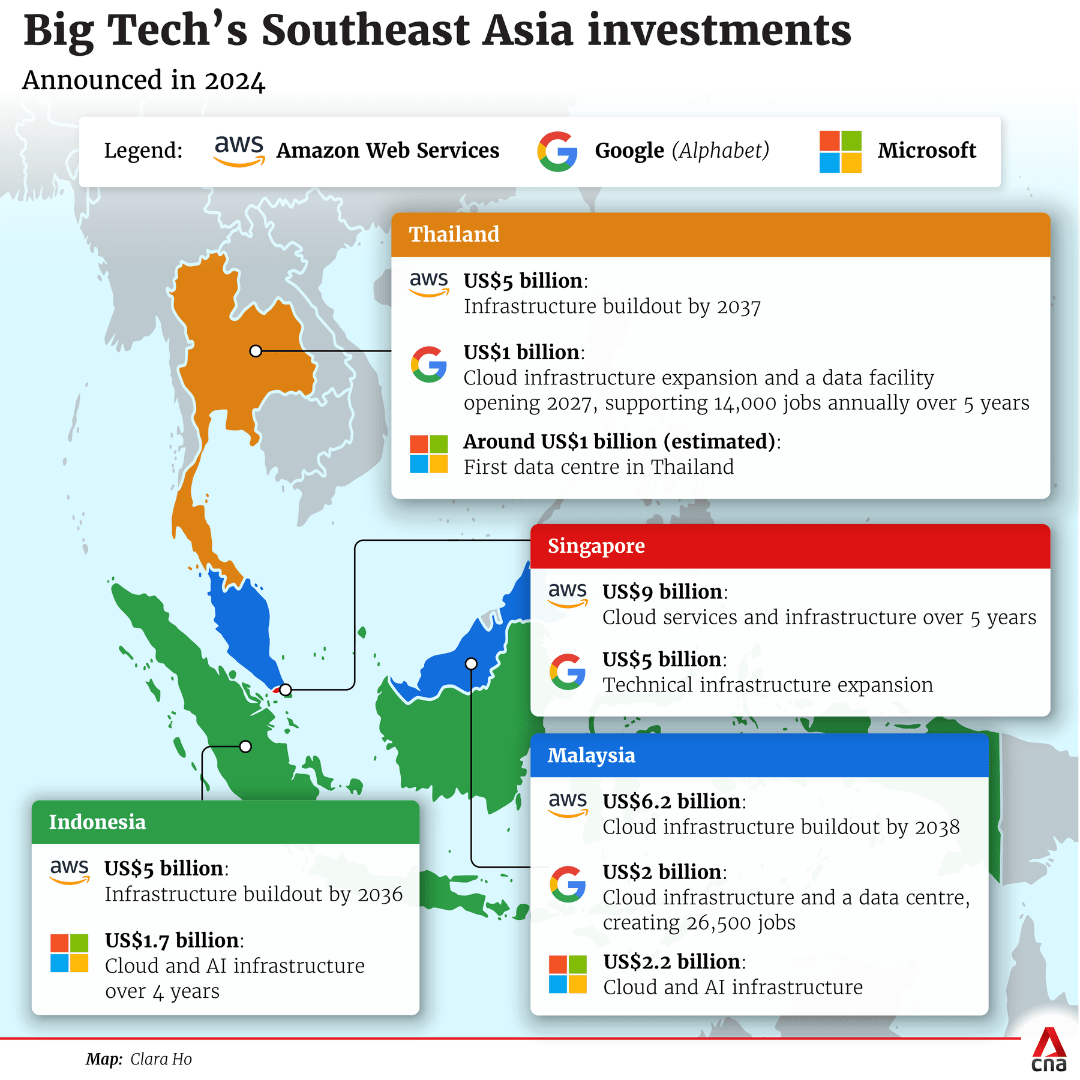

Amid that shortfall, Google, under parent company Alphabet, has pledged billions of dollars of investment across the region in 2024, focused on boosting its data and cloud infrastructure and training millions of people to use AI.

New projects in Malaysia and Thailand headlined the company’s commitments to the region in 2024, as well as a boost in infrastructure and services planned for Singapore.

The company globally has faced headwinds from its rivals, trailing both Microsoft and Amazon Web Services (AWS) in terms of market share for cloud projects, but it has continued to attract a high share of AI customers.

Sapna Chadha, vice-president of the Southeast Asia and South Asia Frontier at Google Asia Pacific, told CNA that the business case for more investment in Southeast Asia was strong, with the “burgeoning of an AI-ready economy” that could help provide solutions in healthcare, education and on climate change.

“All this investment is coming because of the demand. We sometimes hear, is there too much investment happening, is there hype around this? And I would say absolutely not,” she said.

Meanwhile, Microsoft announced multi-billion dollar investments in 2024 including in Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as a target of AI-skilling opportunities for 2.5 million people in the ASEAN region by 2025.

Southeast Asia’s dynamic digital economy is creating a “virtuous cycle of innovation and venture capital inflows”, said Andrea Della Mattea, Microsoft ASEAN’s president.

AWS has made some of the biggest spending promises in recent months, focusing on the long-term buildout of its cloud infrastructure and AI services worth US$11 billion in Thailand and Malaysia alone.

It is working with thousands of customers within the region, including GovTech Singapore, Indonesia’s Ministry of Education and Culture, Petronas, Globe Telecom and Grab to transform their digital services, explained Jeff Johnson, AWS’ ASEAN managing director.

“This includes migrating to the cloud and leveraging new and emerging technologies, such as generative AI,” he said.

Other companies include technology giant Nvidia, which announced in recent months that it would begin investing in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia, and China’s GDS, which raised US$1 billion in investments to expand its regional data offerings in October.

"AN ATTRACTIVE DESTINATION FOR INVESTMENT"

While digitalisation is happening globally, analysts agree that Southeast Asia is positioning itself well to take advantage of a dynamic and lucrative investment environment.

As a single market, the region is home to 660 million people, twice the population of the United States, with a growth rate that outpaces the global average.

“The region is also home to a young and tech-savvy population with 61 per cent of the region’s population under 35 years of age. This all contributes to Southeast Asia being an attractive destination for investments,” said Ming Tan, executive director of the Tech for Good Institute, an independent think tank based in Singapore.

Geopolitics is also a factor, as technology companies look to diversify their investments and seek out regions with friendly policies and stable economies. Southeast Asia increasingly fits the bill, said Khuong from LKYSPP.

“Definitely, investment in ASEAN actually enhances the global competitiveness of tech firms globally,” he said.

“Here you see the emergence of new leadership. Everyone seems to be embracing the digital revolution for growth and so it’s definitely an enabling environment. Incentives, the importance of the markets and geopolitics on entry have become very powerful stimulators of investment uptake for firms in this region,” he added.

Chadha said the “friendliness of Southeast Asia governments is a big advantage” for Google’s investments and business activities.

“Governments and their approach towards this has been to welcome investment and to be open to all sides, which actually gives us an advantage,” she said.

Different governments are offering various sweeteners to draw tech money.

For example, Thailand is offering corporate tax reductions and promoting its fast internet, while Vietnam is offering financial incentives in the research and development space, along with land rental exemptions and preferential credit.

Singapore is framing itself as a start-up incubator hub, attracting top talent to the country’s tech ecosystem and tax reductions that encourage innovation.

Malaysia also has its own raft of grants and incentives while Indonesia has focused on talent development in technology sectors.

Jakarta has been open to working with various technology partners, including those from China, out of pragmatism rather than geopolitics, Kanggrawan said.

“In the public sector in Indonesia, we are getting more open towards China-backed companies, for example. It's very natural. It's just a very fair business and a strategic decision,” he said.

More broadly, ASEAN is aiming for better cooperation among its member states through the Digital Economy Framework Agreement (DEFA), which is currently being negotiated.

DEFA will focus on trade facilitation, e-commerce, digital payments and identity, cybersecurity, data protection, talent mobility and regulatory frameworks, with the overall aim of doubling the projected value of the region’s digital economy by the end of the decade.

The result could be “emboldening business, investor and citizen confidence in the region’s economic prowess”, AWS’ Johnson said.

But he said certain “policy principles” should be considered to maximise its effectiveness, including discouraging data localisation.

While the region is trying to build the right rulebook, artificial intelligence is rapidly being deployed in fields such as education, e-commerce, government services and healthcare.

AI IN THE REAL WORLD

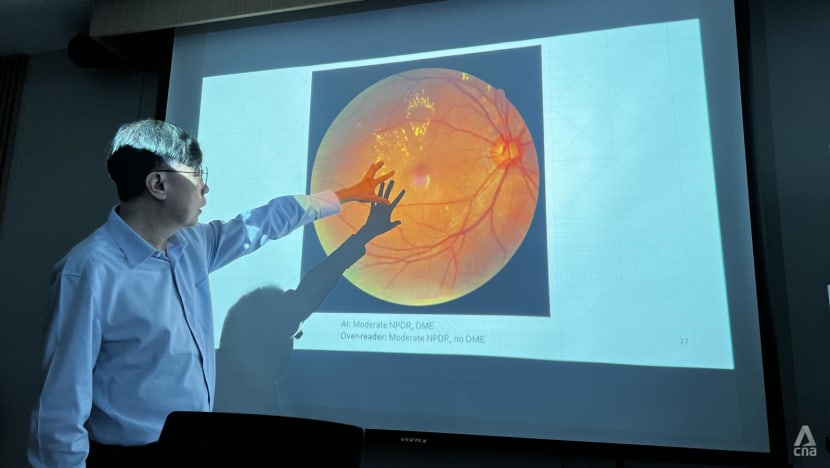

Inside the sprawling wings of Rajavithi Hospital in central Bangkok, Paisan Ruamviboonsuk stands in front of a large projected image of a bright golden sphere.

The ophthalmologist looks like he is inspecting the sun, but he is demonstrating the ways AI is being used to prevent blindness in diabetic patients.

Specialist camera equipment captures an image of the patient's eye, which is then processed by a software programme. Since 2017, the process has then been augmented by machine learning.

In what is called an Automated Retinal Disease Assessment on a web-based platform, AI is able to take the original images and detect and diagnose within seconds whether a patient has diabetic retinopathy, where high blood sugar levels cause damage to blood vessels in the retina, causing them to swell or leak, distorting vision.

Thailand lacks eye specialists and has fewer than 200 of them, according to Paisan. Given that nearly one in 10 Thai adults are estimated to have diabetes and 20 to 30 per cent of those are projected to suffer from vision issues, the potential for technology to expand outreach is promising.

Studies have shown that AI’s accuracy is far greater than non-specialists trained throughout medical clinics in Thailand to diagnose the disease.

Paisan has been collaborating with Google engineers to help pilot and expand this AI solution throughout the country. Some 45 hospitals in Thailand are now deploying it, and he said it complements the work of healthcare professionals.

“We want AI to serve, not take over. We’re still doing our jobs. And patients, they still want to see us, not AI,” he said.

But there are fears around the influence of a constantly evolving technology that, for now, has few guardrails attached to it.

“There is always a serious risk of becoming overly dependent on this kind of technology because this over-reliance will lead to a lack of essential skills,” said Jean Linis-Dinco, a digital rights advisor for the Manushya Foundation, an Asia-focused non-governmental organisation focused on human rights, social justice and peace.

“If healthcare workers, for instance, rely too heavily on AI for diagnostics, there will be a sense of not only not developing the critical skills that are fundamental to their training, but the question is what happens when the AI encounters a scenario where it hasn't been trained.

“Human oversight is not only crucial, but is fundamental in making sure the proliferation or the use of such technology is not just responsible, but also human rights-backed,” she said.

PUTTING A COLLAR ON RUNAWAY TECHNOLOGY

Governments throughout the region are grappling with how to do two seemingly contrarian things at the same time – limiting the influence of AI while also promoting its growth.

“The new challenge for humanity is how to regulate AI, how to adopt AI. So it is something even bigger than the disruption of the internet, arguably,” Kanggrawan said.

“The so-called good news is the situation is not only occurring in Southeast Asia.”

ASEAN launched this year its Guide to AI Governance and Ethics, a non-binding set of guidelines focusing on transparency, fairness, security, reliability, human-centricity, privacy and accountability.

Countries too are at various stages of introducing laws or guidelines that focus on AI and data use. Data sovereignty – rules around how and where local data is stored and who it is controlled by – is also a pressing issue.

Singapore, for example, has developed its Model AI Governance Framework to promote the ethical use of the technology.

Vietnam is drafting a digital technology industry law, while Malaysia launched its National Artificial Intelligence Office last month, which will oversee and set new relevant policies. It also introduced a national cloud policy in October.

Thailand is expected to soon ratify a National AI Committee and Indonesia is also working on an AI governance bill.

Kanggrawan said a certain dilemma still exists for both governments and companies - these policies are needed right now but structural understanding of the evolving technologies remains low.

“When you want to regulate something, you should know about it, right?”

“You are the policy makers, legislative, national, provincial level, better you catch up your knowledge before you make the regulations. Don't only rely on second-hand sources, tech companies, vendors, lobbyists or whatever,” he said.

“It's a model whereby we need to have certain humility. This is going to be very complex.”

In Indonesia, the process could take two or three more years, he said.

Khuong argues that technology companies should be integrated closely in the process given their outsize influence over the issues at hand.

“Regulatory systems are the most critical priority for the governments to address first before talking about initiatives or incentives. And definitely, they should have the tech firms in their mind when designing policies or regulations,” he said.

Linis-Dinco counters that the “scariest ongoing issue” is the risk of surveillance being baked into technologies that are being increasingly relied upon across all sectors of society and the interplay between technology companies and governments.

“Big Tech is definitely more powerful now than many governments, having engineered a lot of this pervasive dependency on their technologies to the point that it's from the time we wake up to the moment we sleep. They're always there,” she said.

“And the concern is not just the erosion of privacy, and that is a crucial part, but it's more on how we are assembling an unprecedented apparatus of surveillance and control that leverages corporate innovation and state authority to the extent that they reach into the lives of ordinary citizens.”

Tech firms told CNA that regulating AI was necessary and they would work closely with governments to achieve strong and fair outcomes.

“AI is too important not to regulate and to not regulate well. Our approach has to be bold and responsible and we want to hold ourselves to that accountability,” Google’s Chadha said.

“We also believe that AI regulation will need to be based on a global policy alignment and mutual recognition of safety frameworks, similar to other domains such as aviation,” said Microsoft’s Della Mattea.

Even if governance catches up, another headwind looms - finding enough workers for the industry.

BROAD TALENT GAPS

Although major technology companies have plans to train millions of people across the region, there is consensus about a looming digital talent gap.

“It is still very difficult, challenging to find a really, really great tech talent. The gap is always there,” Kanggrawan said.

This remains the case even as the industry shed tens of thousands of jobs amid the so-called “tech winter”, a sector downturn of mass job losses and hiring freezes in the past two years.

Khuong said that countries with ageing populations like Thailand and Singapore will have an even “more severe” problem finding manpower.

He said education reforms were necessary regionally and tech firms should be incentivised to help.

“I see the gap everywhere, because the technologies actually progress so rapidly, so everyone has to play the catching up game here to train their people.”

In Thailand, Benja Bencharongkul is running a technology application company called Brainergy, which is parented by Benchachinda Group, a telecommunications group that runs its own data centre and cloud services.

He said the country is facing a major shortage of talented workers, a situation exacerbated for now by the entry into the market of tech giants offering career opportunities and high wages. Local players are left struggling to compete.

“When Google or Microsoft come in, I just see a huge demand increase with, at least in the short term, the same pool of supply (of talent),” he said.

"We are hunting in this same small pool and what we see in the last three years is the 100 per cent or 200 per cent increase in the cost of talent with no significant increase in skill.”

He is concerned that Thailand, which has continued to prioritise economic diversity, will not be able to keep up with its neighbours like Vietnam, which has developed a powerful technology industry.

“In the old Asian mindset, when you ask people what they want to be, a majority might say they want to be a doctor, for example, right? Not in Vietnam anymore. They want to be in tech,” he said.

As digitalisation makes its mark on many aspects of society and business, technology leaders like Benja are worried about countries, especially his, trying to be all things at once.

“We only have 70 million people and we’re producing less and less people for the workforce,” he said, referring to Thailand’s declining birthrate. “So, to please every sector is going to be a lot more demanding.

Governments may have tough decisions to make now and in the years to come. Trying to compete on AI development with global superpowers may prove a fruitless exercise, Kanggrawan said.

Looking for market fit or niche areas to leverage technology could bring more benefits to citizens, he argued.

“And if we can leverage that, even in Southeast Asia, companies or service providers can be global players, but we must be realistic,” he said.

Technology and training programmes have, however, created opportunities for some people with disabilities.

Jidapa Nitiwirakun, 21, was just a toddler when she was diagnosed with muscular dystrophy, a disease that has caused her to lose muscle strength year on year.

As she grew up, she started thinking about jobs that would be suitable for her.

In 2022 and 2023, she participated in Microsoft’s Skills for Jobs programme, which boosted her digital know-how and set her on a path to use AI and coding in her job with trading company Toyota Tsusho.

“I have limitations in living my life, in terms of mobility or going outside very often,” said Jidapa. “But, working with computers can be done at home.”

SUSTAINABILITY CHALLENGES "NOT FOR THE FAINT-HEARTED"

Amid the rush to build more digital capabilities, companies and governments still face a dilemma around their carbon footprint.

Sustainability and environmental impacts are under more scrutiny as economies slowly decarbonise in response to the challenge of climate change.

Yet, the proliferation of data centres is pushing the needle in the wrong direction. Energy use within these centres is sky high.

“Data centres and data transmission networks are estimated to each account for 1 to 1.5 per cent of the global energy consumption,” Tan of Tech for Good Institute said.

“Widespread adoption of AI will push this consumption much higher, as evidenced by the recent disclosures by several of the largest tech companies,” she said.

Microsoft, an investor in ChatGPT maker OpenAI, has seen its carbon emissions rise by 30 per cent since 2020 due to its investments in global data centres.

Likewise, Google saw a 50 per cent increase in 2023 emissions compared to 2019, a situation largely attributed to data infrastructure and needs.

Creating a single AI image can be the equivalent of running a refrigerator for 30 minutes.

The amount of energy to train one generative AI model can be equivalent to powering 130 homes in the US for a year, while training a sophisticated model like Chat GPT-4 was estimated to have used about 50 times that amount of electricity.

In Southeast Asia, where renewable energy access remains patchy, a steep challenge exists for companies with both high power demands and sustainability targets.

According to Maybank’s analysis, greater access to clean energy will further drive growth in the data sector. Investors will be drawn to more sustainable operations and green financing could lead to more economic growth in the sector, the bank found.

ASEAN data centres are improving their efficiencies but still lag behind other regions, it found.

For Google, using AI to find efficiencies within its data centre infrastructure is a key strategy to achieving its global net-zero by 2030 goal.

“There have always been concerns around sustainability, and so I think efficiency is critical,” Chadha said.

“We acknowledge that there are significant energy demands of it and we want to make sure that overall, AI can help address climate change,” she said.

Microsoft said it is looking to cut its supply chain emissions by more than half by 2030, amid a wider goal of to “become a carbon negative, water positive, zero waste company that protects ecosystems - all by 2030”.

AWS said it will “continue to invest in renewable energy in the region and globally to meet our net-zero by 2040 goal”.

STT GDC’s Yeo said there is a need for technology companies to be greener and more efficient in their operations, “which effectively is using less energy for the same set of works”.

The firm is trialling new technologies like carbon capture and greener building materials to reduce its carbon footprint.

“This is one of the most fundamental conflicts we have today; how can we better support the growth of AI, which helps to transform industries and societies, but at the same time minimise the impact to our environment,” Yeo said.

“How do you design data centres to become more efficient? How do you operate in markets that allow you to gain access to renewables? This is not a game for the faint-hearted,” he added.

At present, half of the region’s electricity still comes from coal. Renewable energy capacity will need to more than triple by 2035 in order for countries to meet key decarbonisation pathways, according to Ember, an energy think tank.

That too will require a major boost in investment - a fivefold increase regionally to US$190 billion by 2035, the International Energy Agency reported this year.

The power dilemma is playing out in real time as construction continues on a new STT GDC data centre in Bangkok alongside the existing facility, nestled among apartment units.

Most of Thailand’s energy mix remains dominated by fossil fuels. But Yeo says he sees change happening, broadly, around making the intensive activities needed by this digital revolution less impactful on the planet.

“Although it's a very challenging effort,” he said, “Southeast Asia is starting to see a bit of light beyond the tunnel”.

Additional reporting by Paweena Ninbut