How one Indonesian village turned from hunters into guardians of a rare blue-eyed marsupial

Once viewed as a crop-raiding pest and heavily hunted, the blue-eyed cuscus - a marsupial - is now seen as an ecotourism magnet for one community on the volcanic island of Ternate.

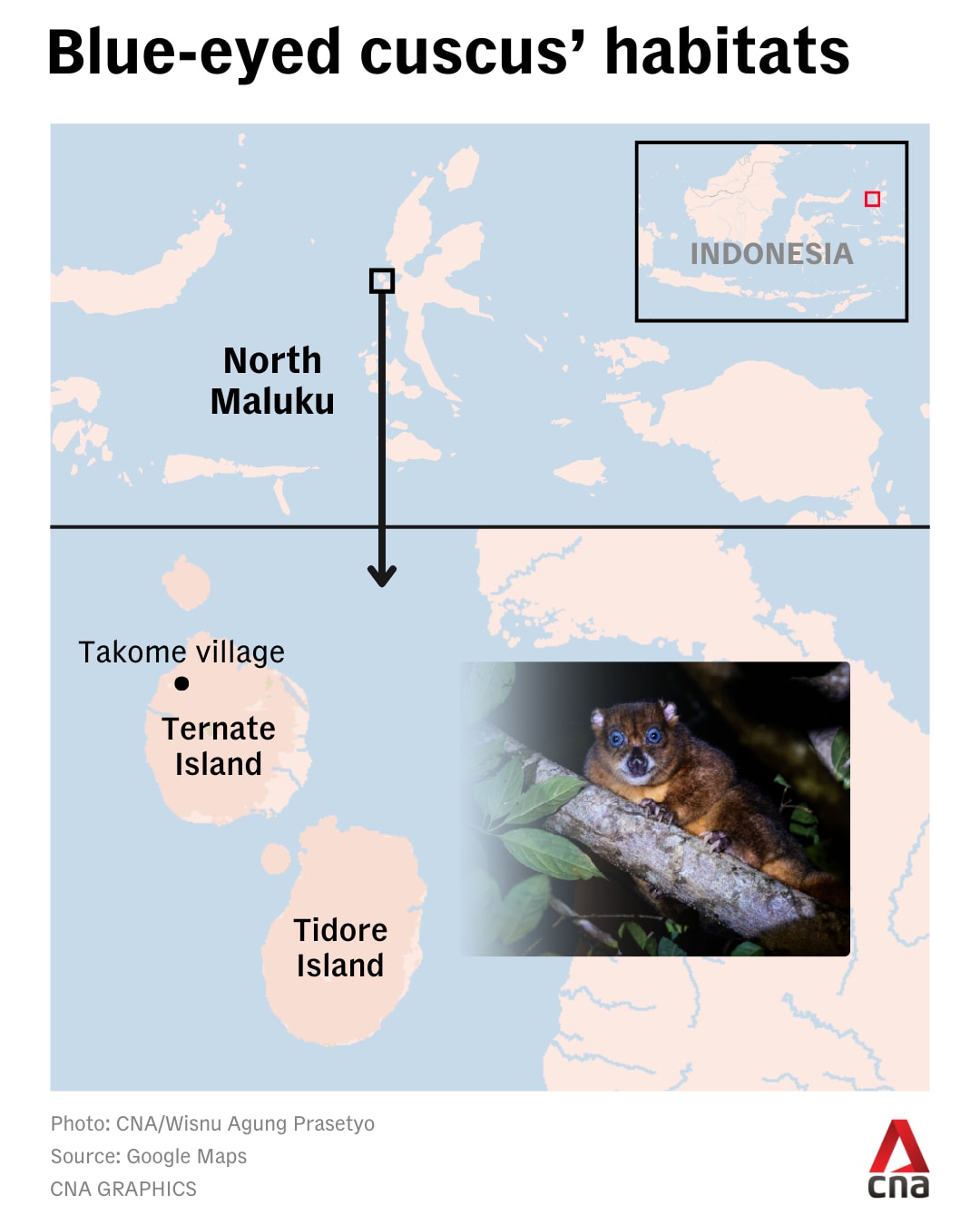

The blue-eyed cuscus is a nocturnal marsupial that is endemic to just two small volcanic Islands in Indonesia's North Maluku province. (Photo: CNA/Wisnu Agung Prasetyo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

TERNATE, North Maluku: Night had just settled as six Takome village youth group volunteers left their camping ground, armed with headlamps, notebooks and phones.

Beams of light swept across footpaths carved out by local farmers as they trekked up a small hill on the north side of Ternate, a volcanic island about one tenth the size of Singapore in the northeastern corner of Indonesia, searching for signs of life.

Within 500m of setting off, the group had already spotted brightly coloured Sahul sunbirds and palm-sized Moluccan dwarf kingfishers resting on the twigs and branches of nutmeg and clove trees. They documented every protected animal they could find.

But it was about 20 minutes in, when they hit the true target of their search. One of the youths shouted: “Kuso! Kuso! Kuso!” - the local name for the blue-eyed cuscus - as he focused his lamp on the rustling leaves high in the forest canopy and all headlamps quickly panned toward a plum tree where the nocturnal marsupial had just been feeding.

The entire group spent the next few minutes marvelling at the cat-sized, golden brown creature as it stared back at them almost motionlessly with its haunting blue eyes.

The blue-eyed cuscus is found only on two small volcanic islands: Ternate and neighbouring Tidore. It is listed as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), threatened by volcanic eruptions, habitat loss and hunting. And it could become even more vulnerable.

“An increase in hunting pressure is most likely to justify a move to a higher threat category in the near future,” the organisation wrote in its latest assessment of the species in 2019.

Officials and experts warn that without intervention, the blue-eyed cuscus could follow the fate of its relatives — the black-spotted cuscus and the Talaud bear cuscus — both now listed as critically endangered due to poaching and habitat loss.

In Takome, the community — even those now fighting to protect the animal — was once part of the problem.

“In fact, many of us who are now involved as (conservation) volunteers were once part of it too. We did the same things (hunting and killing cuscus) as everyone else,” said Takome resident Yuhdi Safi, who now leads nature conservation efforts in his village.

The slight, soft-spoken 29-year-old said residents used to view cuscus as pests that damaged crops such as durians, nutmegs and Java plums.

“They had no idea that the blue-eyed cuscus is a protected species endemic to Ternate and Tidore,” he said.

That perception is gradually changing. Today, Yuhdi said the youths in his village have retired their slingshots and air rifles, and those who once hunted cuscus now patrol the forest, watching for poachers and outsiders entering their land.

THE LAST BASTIONS OF THE BLUE-EYED CUSCUS

Locals and officials say Takome could well be one of the last bastions of the blue-eyed cuscus.

The area is rich in food for the marsupials, which feed on fruits, leaves and small insects. Habitat loss is minimal as Takome lies directly in the path of lava and mudflows from the active Mount Gamalama and thus sits on the least developed and least populated side of the island.

One of the 1,700m volcano's last major eruptions was in 2015, forcing the evacuation of thousands, including residents of Takome.

But the natural disaster was a minor threat to the marsupial, compared to human danger. Takome resident Junaidi Abas said hunting cuscus was once a favourite pastime among local children and youths.

“After school, we would head straight into the forest to hunt for cuscus. As children, we used slingshots, and when we got older, we hunted with air rifles,” the 34-year-old said.

Cuscus were easy targets. They are slow-moving and become even less active once they are full. When a light is shone on them, they often become disoriented and freeze.

People from outside Takome also frequented the forests around the village, hunting for sport or to satisfy a taste for exotic meat. Hunting, Junaidi said, occurred almost every day, sometimes attracting as many 10 hunters at a given time.

“(Cuscus) hunting by villagers and outsiders was extremely widespread. In a single night, they could take five to six sacks of cuscus,” Junaidi said, adding that each sack could hold between 10 and 12 adult animals.

Because cuscus are marsupials that carry their young in pouches, hunting often resulted in the deaths of dependent young as well.

Things began to change in 2019, when several youths in Takome came up with the idea of opening a camping ground in Pulo Tareba, an abandoned farmland at the edge of a steep 30m cliff overlooking a circular lake.

With funding from the village, the youths sourced timber from felled trees and built gazebos, viewing platforms and a two-storey wooden building which doubles as a cafe and a living quarters for volunteers manning the camping ground.

These wooden facilities took just weeks to build and soon, the Pulo Tareba conservation and camping ground was open to the public.

The camping ground proved to be a hit, not only with the locals of Ternate eager to watch the sun set over the water below, but also with far-flung birdwatchers, researchers and scientists drawn by Takome’s rich biodiversity.

“These activists and scientists told us that the cuscus in Takome is special and can be found only in Ternate and Tidore,” Yuhdi said. Over time, villagers began to realise they could earn more by guiding researchers to see the blue-eyed cuscus than by hunting it.

“Our village also happens to have fairly strong tourism potential. That became one of the reasons we used to tell people not to do things like hunting cuscus. Because the more people hunt the less likely outside tourists are to come.”

Both hunters and researchers charge the same amount for guide services which can vary between 20,000 rupiah (US$1.19) to 100,000 rupiah a night. But with tourists and researchers, they can also sell food, rent tents and charge entrance fees.

“And working with tourists and researchers is more sustainable because we are protecting the very species people come to see,” Yuhdi said.

Still, changing perceptions — from seeing the blue-eyed cuscus as a pest to recognising it as a species in need of protection — has not been easy, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic when researchers and tourists stopped coming.

“Thankfully we managed to get people in our village to stop hunting. In fact, nowadays if they find an injured cuscus they would bring it to us so we can treat it and care for it,” Yuhdi said.

CUSCUS UNDER CONTINUED THREAT

But the threat is far from over.

Despite growing awareness within Takome, the forest around the village remains a magnet for hunters from outside the community, drawn by the abundance of blue-eyed cuscus that still survive there. Word has spread that the species is easy to find, and under cover of darkness, outsiders continue to enter the area to hunt, often during full-moon nights when visibility is best.

Takome resident Junaidi said in 2023, the community took the initiative to patrol the forest regularly. Since patrolling began, the community has so far foiled three cases of poaching, including one in December where 15 adult cuscus and four younglings were seized from four hunters.

“We noticed that there were flashlights on the other side of the (water). They were making their way deeper into the forest and we sent a few of our guys to investigate. And sure enough when we got close to them we heard gunshots,” Junaidi said of the December case.

Residents then alerted local police and officials from the North Maluku Natural Resource Conservation Agency. Working together, they intercepted the four hunters as they emerged from the forest and headed toward nearby residential areas.

Ahmad Doyada, a senior forest ranger with the agency, said that with just four personnel responsible for the 76-sq-km island, authorities rely heavily on the Takome community as their eyes and ears on the ground.

“We have limited personnel, and the area is quite far from our base, so we ask for help from the community. If anyone is hunting, we ask them to inform us,” Ahmad said.

Doyada said his office has begun installing warning signs stating that hunting the protected species is illegal and punishable by up to five years in prison, a fine of up to 100 million rupiah, or both.

“The hunters often claim they didn’t know the blue-eyed cuscus is a protected species,” he said. With the signs in place, Doyada hoped there would be no more excuses for leniency.

The BKSDA official said the North Maluku province is also drafting a provincial regulation which will strengthen the protection and conservation efforts of the blue-eyed cuscus.

The drafting process is still ongoing. After the draft is ready it must be deliberated by the local legislature before it is passed into law. The deliberation process can take months or even years to complete.

TAKOME TAKES MATTERS INTO ITS OWN HANDS

Doyada said there has been no official study of the blue-eyed cuscus population, adding that the lack of knowledge complicates conservation efforts.

Without baseline data on how many animals remain or whether numbers are rising or falling, authorities have little way of measuring the true impact of hunting or habitat loss.

The absence of population estimates also makes it harder to justify stronger protections, secure funding or design long-term management plans tailored to the species’ needs.

With little formal research, the community in Takome has taken matters into its own hands. Villagers conduct regular forest expeditions, documenting sightings, behaviour and locations of blue-eyed cuscus and other wildlife.

Takome resident Yuhdi hopes that these records can offer valuable insights to researchers — pointing to key habitats and seasonal patterns which may help scientists identify trends and build a clearer picture of a species that remains largely understudied.

“We often have discussions with visiting researchers about what they need and how the community can help,” he said.

In exchange, conservation groups and scientists conduct workshops to train local volunteers in basic wildlife monitoring, species identification and data recording, equipping them with the skills needed to document animals accurately and safely in the forest.

These groups also helped make the camping ground more sustainable, providing practical tools such as motion-sensor lamps and solar panels, as well as sharing know-how on waste management — from plastic bottle collection systems to composting — reducing the site’s environmental footprint.

Since the camping ground emerged from a pandemic-induced hiatus in 2022, the Takome village youth group has earned praise and recognition from organisations in Ternate and beyond.

Some companies have since provided donations, allowing the site to expand.

“We’ve recently added cabins so guests who don’t want to spend the night in tents have somewhere comfortable to stay,” Yuhdi said. He added that he also hopes to build birdwatching platforms and camouflaged hides, so visitors can observe wildlife without disturbing it.

The site is now busier than ever, drawing tourists, nature enthusiasts and scientists from across Indonesia and around the world. During the school holiday season, the Pulo Tareba camping ground can welcome as many as 200 tourists a day.

Community involvement has grown as well, with more villagers pitching in — helping with construction, day-to-day operations and conservation patrols. Even those with full-time jobs often lend a hand after returning home in the evenings.

But for the volunteers, the biggest reward has been seeing the cuscus return.

“When we first started, we could spend an entire night without encountering a single cuscus. These days, it can take less than a 15-minute walk before the first encounter,” Yuhdi said.

“I hope it’s a sign that all the hard work we’ve put into protecting the cuscus is finally paying off.”