CNA Explains: Typhoons and hurricanes – what’s the difference and how are they named?

Why do we name typhoons and hurricanes, and could climate change put Singapore in the path of one of these weather events? CNA finds out.

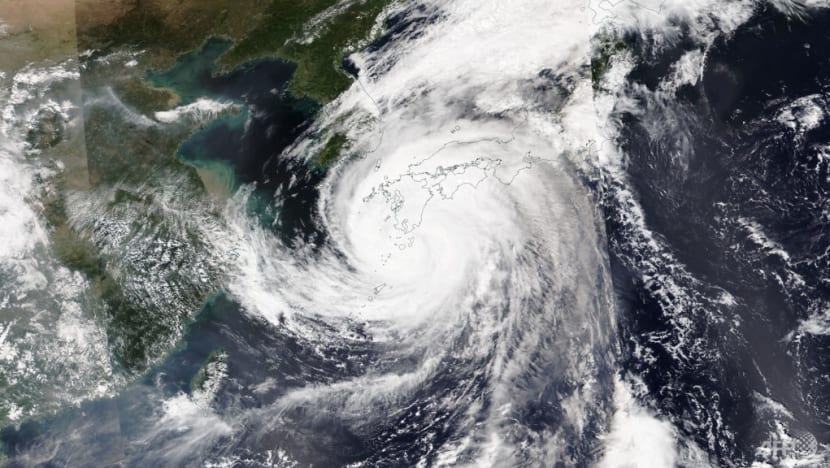

This NASA Worldview satellite image collected on Sep 18, 2022, shows Typhoon Nanmadol over southern Japan. (Image: AFP/NASA)

SINGAPORE: In recent weeks, the planet has been lashed by a series of typhoons and hurricanes.

Since the end of August, the Atlantic Ocean has seen hurricanes Danielle, Earl and Fiona, with Hurricane Ian now bearing down on Florida.

At the same time, countries along the Pacific Ocean were battered by typhoons Hinnamnor, Muifa and Nanmadol before Noru made landfall.

But what is the difference between a typhoon and a hurricane? How do they get their names? And could climate change put Singapore in the path of one of these weather events?

Here is what you need to know:

TYPHOON OR HURRICANE - WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE?

According to the National Ocean Service of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), typhoons and hurricanes are the same thing – tropical cyclones.

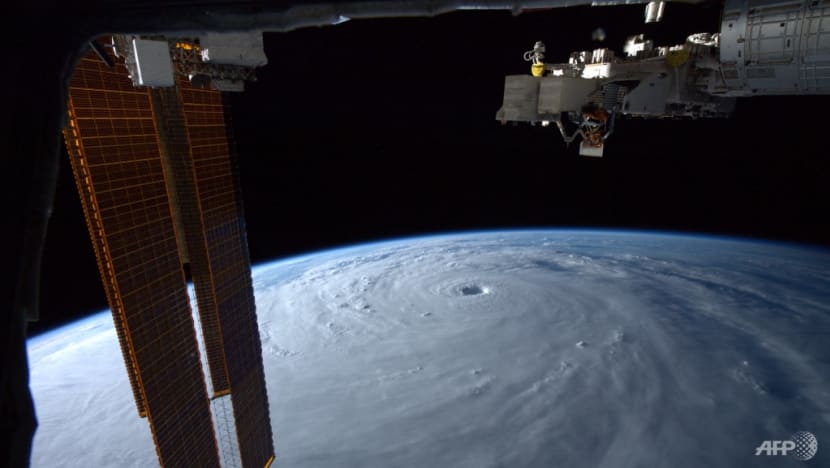

"A tropical cyclone is a generic term used by meteorologists to describe a rotating, organised system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or subtropical waters and has closed, low-level circulation," NOAA said on its website.

The only difference between them is where they occur.

"In the North Atlantic, central North Pacific and eastern North Pacific, the term hurricane is used. The same type of disturbance in the Northwest Pacific is called a typhoon," NOAA said.

"Meanwhile, in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean, the generic term tropical cyclone is used, regardless of the strength of the wind associated with the weather system."

Tropical cyclones start out as tropical depressions, and should they intensify to have maximum sustained winds of at least 34 knots (about 63kmh), they become known as tropical storms.

If they intensify further with maximum sustained winds of at least 64 knots (about 119kmh), they are classified as typhoons or hurricanes.

Tropical cyclones in the northern hemisphere rotate in a counterclockwise direction, while those in the southern hemisphere spiral in a clockwise direction.

Related:

HOW AND WHY DO WE NAME THEM?

To put it simply, tropical cyclones are named to avoid confusion and streamline communications, said NOAA.

The US began giving hurricanes short and distinctive names in 1953, initially only using female names. By the late 1970s, this had expanded to include male names.

Hurricanes and typhoons are named according to a procedure established by the United Nations' World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

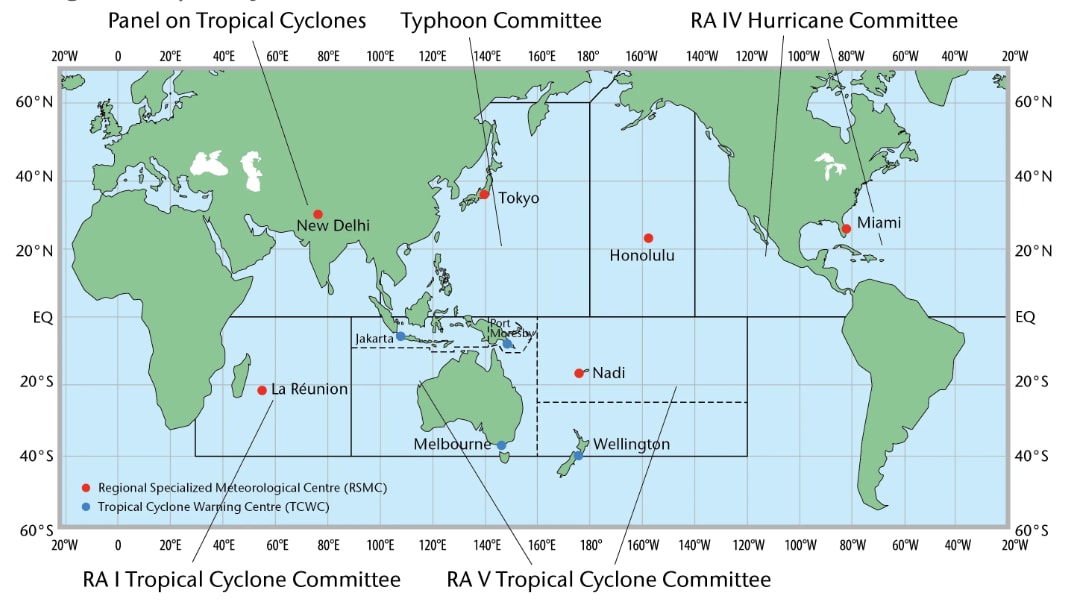

There are five regional bodies that are responsible for establishing lists of names for tropical cyclones in designated areas.

They are the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP)/WMO Typhoon Committee, the WMO/ESCAP Panel on Tropical Cyclones, the Regional Association I Tropical Cyclone Committee, the Regional Association IV Hurricane Committee and the Regional Association V Tropical Cyclone Committee.

The WMO Regional Association I Tropical Cyclone Committee is responsible for the south-west Indian Ocean while the WMO Regional Association V Tropical Cyclone Committee covers the south-east Indian Ocean and the South Pacific.

The WMO Regional Association IV Hurricane Committee covers North America, Central America and the Caribbean, and provides names for tropical cyclones in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the North Atlantic and parts of the Pacific.

For the Atlantic and eastern North Pacific, there are six lists of names that are used in rotation on an annual basis. This means that names used in 2022 will be reused in 2028.

The lists run in alphabetical order – excluding Q, U, X, Y and Z in the Atlantic and Q and U in the Pacific – with male and female names alternated.

This year's progression in the Atlantic so far has been Alex, Bonnie, Colin, Danielle, Earl, Fiona, Gaston, Hermine and Ian. Up next on the list are Julia, Karl and Lisa.

Supplemental names are available should a list be exhausted.

The Regional Specialized Meteorological Center (RSMC) Tokyo - Typhoon Center assigns names in the western North Pacific and South China Sea based on a list of names adopted by the ESCAP/WMO Typhoon Committee.

This committee, which counts Singapore among its members, was established in 1968.

Finally, the Regional Specialized Meteorological Center in New Delhi names tropical cyclones in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal based on names adopted by the ESCAP/WMO Panel on Tropical Cyclones.

Names adopted by the Typhoon Committee and the Panel on Tropical Cyclones are submitted by member countries and territories. The use of these names follows the alphabetical order of their submitters' names.

Laos provided the name for Hinnamnor, Macao for Muifa, Malaysia for Merbok, Micronesia for Nanmadol, the Philippines for Talas and South Korea for Noru.

Up next on the name list are Kulap (provided by Thailand), Roke (provided by the US) and Sonca (provided by Vietnam).

The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration also gives its own names for tropical cyclones within a specific area of responsibility around the country.

When a tropical cyclone is particularly deadly or costly, its name can be retired from use. This was the case for Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017 and Typhoon Mangkhut in 2018.

Hurricanes that cross from the Atlantic into the Pacific – as Bonnie did in July – retain their names. The same goes for tropical cyclones that travel from the South China Sea to the Bay of Bengal over Thailand, and those that shift from the south-east Indian Ocean to the south-west Indian Ocean.

Related:

WHAT ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE?

Conversations about tropical cyclones inevitably lead to the subject of climate change and its impact on these weather events. Are they becoming more intense as the planet warms?

Professor of Urban Climatology at the National University of Singapore's Department of Geography Matthias Roth thinks so.

"Current understanding is that human-induced climate change is likely increasing the intensity of tropical cyclones – tropical storms, hurricanes and typhoons – because of warming of the surface ocean," he told CNA.

"In addition, increased atmospheric moisture associated with global warming is also likely to increase rainfall rates in tropical cyclones."

Earth Observatory of Singapore director and Nanyang Technological University Asian School of the Environment professor Benjamin Horton agrees.

"Climate change is making typhoons and hurricanes wetter, windier and altogether more intense," he told CNA.

"There is also evidence that it is causing typhoons and hurricanes to travel more slowly, meaning they can produce more rainfall in one place."

Prof Horton said that the ocean has absorbed about 90 per cent of the climate warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions. Much of this heat, as Prof Roth also highlighted, is contained near the water's surface.

"This additional heat can fuel a typhoon and hurricane's intensity and power stronger winds," he said.

Prof Horton explained how the amount of rainfall delivered by typhoons and hurricanes has been boosted by climate change.

"Because a warmer atmosphere can also hold more moisture, water vapour builds up until clouds break, sending down heavy rain," he added.

"The Earth's climate has warmed approximately 1 degree Celsius, which means the atmosphere can hold 7 per cent more moisture."

Prof Horton noted that NOAA scientists believe typhoon and hurricane wind speeds could increase by up to 10 per cent should warming hit 2 degrees Celsius.

NOAA has also predicted that the proportion of typhoons and hurricanes that reach the most intense Category 4 or 5 levels could rise by about 10 per cent this century, he said.

In addition to this, rising sea levels mean that storm surges get higher during typhoons and hurricanes, Prof Horton said. This allows water to travel further inland, which worsens flooding.

Related:

COULD SINGAPORE END UP IN THE PATH OF A TROPICAL CYCLONE?

With waters warming, the areas affected by tropical cyclones are growing larger. The time frame when these events occur is also expanding.

"Because warmer water helps fuel typhoons and hurricanes, climate change is enlarging the zone where typhoons can form. There is a migration of tropical cyclones out of the tropics and toward subtropics and middle latitudes," said Prof Horton.

"The typical 'season' for typhoons and hurricanes is shifting, as climate warming creates conditions conducive to storms in more months of the year."

Singapore will, however, probably be spared from the brunt of this, said Prof Roth.

"It is very unlikely that Singapore will be affected by such weather events, due to a lack of Coriolis effect near the equator which prevents the formation of tropical cyclones," he said.

Still, the Earth Observatory of Singapore is studying how climate change might influence tropical cyclones that have the potential to affect the country, said Prof Horton.

"Tropical Storms that develop over the Indian Ocean or western Pacific Ocean can influence the winds over the (surrounding) regions of Singapore," he said.

"Depending on positions of the tropical storms as they track over large bodies of water of the South China Sea and the western Pacific Ocean, the tropical storms can induce and affect the weather in Singapore."

Singapore has actually been impacted by a tropical cyclone before – Vamei in December 2001 – although Prof Roth shared that there is some debate about its intensity and whether it should be classified as a typhoon or tropical storm.

Prof Horton described how unusual this event was.

"It's a lesson in Meteorology 101: Hurricanes can't form near the equator. However, the storm called Typhoon Vamei violated that edict in December 2001, arising just 150km north of the equator in the South China Sea, near Singapore," he said.

"Analysis of the strange atmospheric behaviour that spawned the typhoon shows that such a storm may occur just once every few centuries. But this may change as the climate warms."