analysis Asia

Johor quakes a reminder that severe tremors can impact Malaysia, Singapore

The two mild earthquakes that struck northern Johor on Sunday (Aug 24) occurred in the Mersing Fault Zone, which has previously triggered bigger quakes exceeding 5.0 in magnitude and could do so in the future, say experts.

Photos shared on social media showed debris from the ceiling falling and cracks on the walls of a home after a 4.1-magnitude earthquake hit Segamat in Johor, Malaysia on Aug 24, 2025. (Photos: Facebook/Komuniti Segamat)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JOHOR BAHRU: The two mild earthquakes over the weekend in Johor serve as a reminder that Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and the surrounding region are not immune to the natural disaster that could trigger severe tremors and inflict damage to people and property, say geological experts.

They add that there is precedent of earthquakes occurring in the area, citing examples of how a pair of earthquakes - which measured above 5 on the Richter scale - occurred in 1922 in Johor that were widely felt. There was also a tremor in 1948 felt near southern Singapore that inflicted damage to property.

These experts also suggested that authorities adopt monitoring measures to better understand seismic activities in the region and have in place warning systems to communicate timely and potentially life-saving information to the masses.

“(Sunday’s) earthquake is a reminder - the Johor region already experienced even larger earthquakes (back) in 1922 - that at least some of the faults in the Malay Peninsula are active, even if earthquakes in the (area) are rare,” Aron Meltzner, an earthquake geology expert from Nanyang Technological University’s (NTU) Earth Observatory of Singapore, told CNA.

On Sunday (Aug 24), a pair of earthquakes struck northern Johor, triggering tremors in several Malaysian states including Negeri Sembilan, Melaka and Pahang. Netizens documented damage from the earthquakes, including falling debris from the ceiling and cracks on the wall.

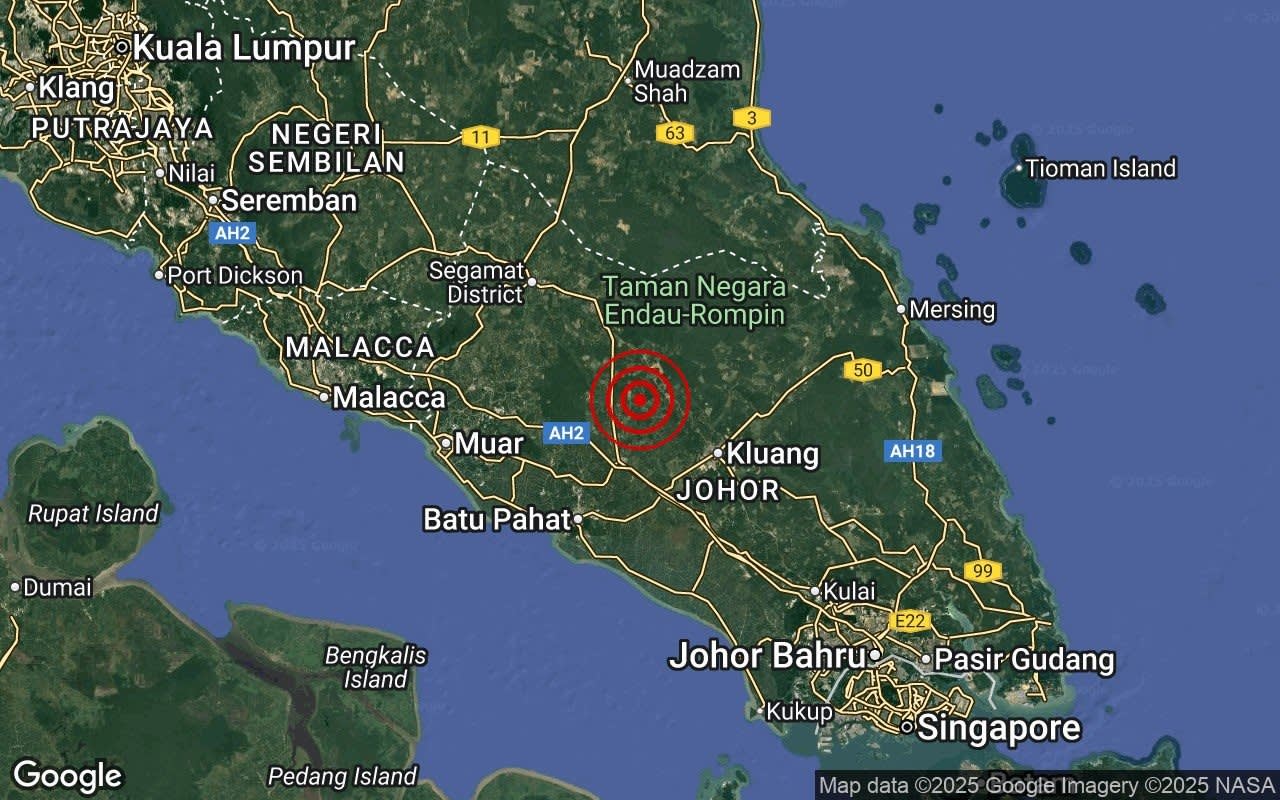

An initial 4.1-magnitude quake occurred at about 6.15am, 5km west of the town of Segamat at a depth of 10km, while a second, milder quake of 2.8-magnitude occurred at 9am, 28km northwest of Kluang town.

According to a statement from the Malaysian Meteorological Department (MetMalaysia), both earthquakes had epicentres near the Mersing Fault Zone, a major fault belt in the peninsula. There were no reported loss of life or injuries as a result of the earthquakes.

RISK OF LARGER EARTHQUAKES SMALL BUT ‘NOT ZERO’

MetMalaysia’s director-general Mohd Hisham Mohd Anip told CNA that while earthquakes do occur in the region, they are likely to be minor ones and the impact on life and property is expected to be small.

He said that the Mersing Fault Zone, an area concentrated with crustal plate boundaries, is not as active as fault lines in Sabah for instance.

“Based on existing records of seismic activity in Peninsular Malaysia, earthquake magnitudes are weak and do not (usually) exceed magnitude 5. Therefore, tremors from this zone are not expected to have a major impact,” said Hisham.

Yet, geologists whom CNA spoke to said that the incidents on Sunday are clear indications that the faults are still active, and that earthquakes of magnitude up to 6 could occur in the future in the region.

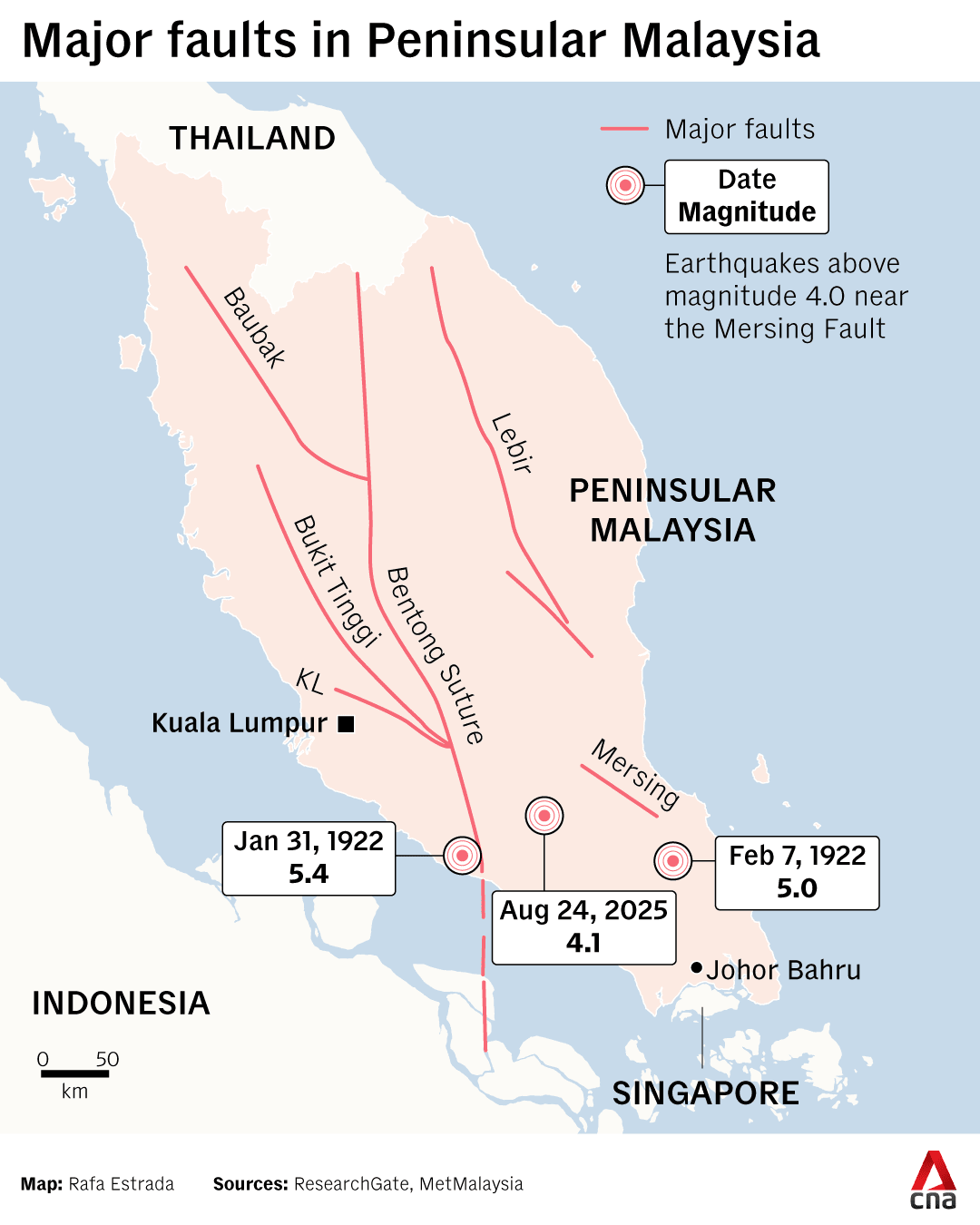

The Mersing Fault Zone is one of the major fault belts in the peninsula, along with others like Bukit Tinggi, Kuala Lumpur, Lebir, Bok Bak, Bentong, and Lepar.

Experts said the quakes show that such seismic activity does occur in the Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore region as a result of intraplate tectonic motion.

Intraplate tectonic motion refers to tectonic processes - such as faulting and folding - within the tectonic plate rather than its boundaries.

They added that this is even as the area is far removed from the Pacific Ring of Fire where interboundary plate movements trigger more serious earthquake activity. The nearest earthquake zone to the area is in Sumatra, around 400km from Singapore.

Azlan Adnan, a fellow with the Academy of Sciences Malaysia (ASM) told CNA that the location of the epicentre of the two earthquakes on Sunday reinforces the point that the fault is “indeed active”.

“The alignment of the incident is also consistent with regional fault patterns (roughly northwest–southeast), suggesting the possible reactivation of an old fault,” said the earthquake engineering expert.

He added that records of earthquakes due to major faults in the peninsula indicate that tremors with magnitudes of up to 5 have occurred periodically, and even magnitude six in rare cases.

“Considering the Mersing Fault (Zone), which could be at least 20km long, if it ruptures in full, a magnitude of up to magnitude 6.5 could occur. This means that the possibility of a larger earthquake does exist,” added Azlan.

Geologist Wei Shengji of NTU’s Asian School of Environment told CNA that there is precedent of significant earthquakes occurring - citing two tremors in 1922 with epicentres in Johor state. The tremors were recorded at magnitude 5.0 and 5.4, with the former near the Mersing Fault Zone while the latter near the Bentong Suture.

“There is a chance that larger earthquakes could take place in the future, as bigger events (such as those in 1922) did occur in the past. The 1922 events were widely felt in Singapore,” he added.

Meltzner, meanwhile, said that there was an earthquake in December 1948 near southern Singapore and that the tremors were felt widely in Geylang, Bukit Timah, Sentosa island and reportedly damaged a house in Chinatown.

“Because the shaking in 1948 was similar to what people felt (on Sunday), the 1948 earthquake was probably also about magnitude 4, but much closer to Singapore, demonstrating that earthquakes happen in Singapore, too, even if they are rare,” said Meltzner.

Environmentalist Renard Siew, who is the climate change adviser to the Centre for Governance and Political Studies (Cent-GPS), a Malaysia-based behavioural and social science research firm, added that climate change could in the future exacerbate the frequency of earthquakes, albeit indirectly.

Citing studies done in India and Taiwan, he said that higher rainfall due to climate change have led interactions to the soil and ground earth, and this triggers more seismic activities in certain areas.

“Climate change doesn’t cause earthquakes directly but it can definitely amplify conditions for seismic risk,” said Siew.

MORE MONITORING KEY TO UNDERSTANDING SEISMIC ACTIVITIES

Geologists added that authorities in this region should consider allocating more resources to understanding earthquake activities in this region to mitigate their risks to public safety.

ASM’s Azlan posited that the current situation in the Mersing-Segamat corridor was “serious” and that authorities should consider installing more seismometers and a strong-motion accelerograph network in the southern part of the peninsula to record actual site tremors.

An accelerograph network is a system of connected accelerographs - which are instruments that measure the intensity of strong ground motion during an earthquake - deployed across a region to collect data.

Azlan added that it was also important for the lines of communication to the public to be integrated with MetMalaysia updates and that more audits be done for buildings and critical infrastructure to ensure they comply with the building code.

Meltzner of NTU added that increased monitoring of seismic activities - both in Malaysia and Singapore - would help scientists better understand the hazards in the Malay Peninsula.

However, he warned that a truly effective warning system must be customised to fit the requirements of the region, and warned that a reliable system could take years to develop.

“In California, this took more than two decades to develop, and it’s still not perfect,” said Meltzner.

Experts also expressed concerns over how earthquakes could impact rail network systems in the region, especially with Malaysia beefing up its railway infrastructure through projects like the East Coast Rail Link and other high-speed rail initiatives.

Azlan outlined how the public transport systems like Malaysia’s Electric Train Service, which currently runs between Kluang in central Johor to Padang Besar near the Thai border, must be inspected after earthquake incidents near its tracks.

NTU’s Wei highlighted that strong shaking and ground deformation generated by earthquakes “has always been a threat to infrastructure” including rails.

Azlan warned that the impact of the earthquake on soil could disturb track geometry. Moreover he added that components like bridge bearings, expansion joints and electrical equipment may be disrupted.

“Operators must have ‘post-event’ standard operating procedures (SOPs), including visual inspections/automatic geometry measurements, maximum acceleration thresholds for speed restrictions, and instrumentation on long bridges,” said Azlan. who is also deputy president of the Malaysian Structural Steel Association.

“Considering that the (ETS) line is nearing completion … installing accelerographs on the main structures of this corridor would be a low-cost, high-impact step that supports both seismic design development and future operations,” he added.