'Enormous machine spreading disinformation' casts shadow over Philippine presidential contest

Political campaigners are using sophisticated and organised methods to mislead the public, getting them to buy into messages crafted by advertising experts, influencers and trolls.

Campaign posters of various candidates in the Philippine national and local elections in Manila. (Photo: CNA/Pichayada Promchertchoo)

MANILA: On Apr 10, Filipino social media personality Jam Magno tweeted that a rally of presidential candidate Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr in Tacloban the day before was attended by 300,000 people.

However, local news outlets reported that the crowd at Leyte Sports Development Center, where the event took place amid heavy rain, was estimated at about 150,000 - half of what the Internet personality claimed. In fact, the estimated maximum capacity of the event venue based on mapchecking.com is less than 85,000.

Subsequently, local fact-checking initiative tsek.ph labelled the tweet as a false claim.

The claim by Magno, who has 75,000 Twitter followers and is an avid supporter of Bongbong, is just one example of information that is seeking to mislead Filipinos in the run-up to the presidential election on May 9.

Through technologies and the expanding Internet access, campaigners are using sophisticated and organised methods over time to influence the public, getting them to buy into messages crafted by advertising and PR experts, influencers and trolls.

These campaigns have cast a shadow over the electoral process. For those involved in fact-checking, their work is often an uphill task.

DIGITAL DISINFORMATION “A REAL INDUSTRY”: EXPERT

Disinformation refers to how disseminated content is deliberately designed to mislead people.

According to communication expert Jason Vincent Cabanes, digital disinformation has developed into “a real industry” in the Philippines. It offers jobs to content producers, whose roles vary within a hierarchy.

These people are tasked with seeing through information campaigns in exchange for money, new gadgets and a lavish lifestyle. Their activities can last for years but often heighten during the election period.

“We’re seeing the impact of digital disinformation campaigns that don't just happen during election periods. It's a sustained kind of campaign over many years to try to burnish the reputation of a particular politician or make people more open to particular policies,” said Cabanes, a professor and researcher at the communication department of De La Salle University in Manila.

He has been studying digital disinformation in the Philippines since 2016, shortly after Rodrigo Duterte was elected president. False information was found to have penetrated popular social media platforms such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter.

Increasingly, however, campaigners are using private group chats on messaging apps such as Messenger, WhatsApp and Viber to spread disinformation.

“Although you still see a lot of disinformation on your walls or the news feeds of your accounts, a lot of it is also happening in the small groups. It’s harder for academics to take a look at, harder for regulators to spot. And that creates a whole host of other problems,” said Cabanes.

“VENEER OF DECENCY”

Such campaigns usually have a sleek and professional sheen to them. Team members - particularly those who have to interact with people outside the organisation - are known by titles such as “digital political campaigner'' and “digital political consultant”, who work with “digital influencers”.

“They actually use the language of advertising and PR for these things and of course, the language of the long-standing industry of political campaigning too,” Cabanes told CNA.

“They hide in the veneer of decency of those kinds of industries.”

The communication expert told CNA that he met with a local campaigner during the course of his research. The latter was considered “the chief architect of network disinformation”.

The role is at the top of the network hierarchy. It involves mapping out media strategies and relaying campaign messages to others in the team.

According to Cabanes, these architects mostly operate on Twitter, where they create several accounts and avatars to communicate the messages they want to circulate. The messages then cascade to Facebook and YouTube.

“These are people who have come from the advertising and PR industries - former executives in big companies,” he said. “And because of their expertise, they're now hyper-extending the techniques of Ad and PR and of branding to the realm of politics.”

Below the architects are digital influencers - creatives who translate the strategies into actual misleading content, making them more understandable and relatable.

Those who create content that attracts the most likes, shares or retweets are rewarded with a bonus. Sometimes, Cabanes said, it comes in the form of a new MacBook, an iPad or the newest iPhone.

Right at the bottom of the pyramid are community-level account operators, who amplify the messages. Many of these community-level operators are young college students who need money for tuition or family support.

“These are the ones whom we meet on our social media feeds - those we fight with,” the expert said. “They're mostly copy-and-paste, code-and-go trolls.”

A “DAVID AND GOLIATH FIGHT” AGAINST DISINFORMATION

There are 65.7 million registered voters for the upcoming national and local elections in the Philippines. These include the presidential election, in which 10 candidates are contesting.

The frontrunners are former senator Bongbong and incumbent Vice President Maria Leonor “Leni” Robredo. Their running mates are Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte and Senator Francis Pangilinan respectively.

Bongbong is the son of the late president Ferdinand E Marcos, whose authoritarian regime was marred by corruption and human rights abuse. He and Leni also competed in the vice presidential race back in 2016, when the latter emerged the winner.

This time, however, pre-electoral surveys showed Bongbong in the lead. Based on the latest poll by Philippines-based opinion polling body Pulse Asia Research Inc, 56 per cent of 2,400 respondents would choose him as their new president while 23 per cent would vote for Leni.

“You have positive disinformation - disinformation that makes a candidate look good - and negative disinformation, which makes a candidate look bad,” explained Rachel E Khan from tsek.ph, a fact-checking initiative for the May 9 elections.

Tsek.ph is an independent collaboration between academia, media and civil society to fight disinformation and offer verified information to the public. The platform focuses on campaign promises, election-related statements and social media posts.

In February, it released a preliminary analysis of fact-checking carried out in relation to the May 9 polls. It found that misleading information mainly revolved around Bongbong and the vice president.

“Data shows Robredo reeling from preponderantly negative messages and Marcos Jr enjoying overwhelming positive ones. Of the false or misleading narratives involving Robredo, 94 per cent were aimed against her, while all the narratives that mentioned her running mate, Senator Francis Pangilinan, were likewise negative,” tsek.ph reported on Feb 25.

“On the other hand, nine in 10 of narratives about Marcos Jr and his running mate, Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte, favoured them.”

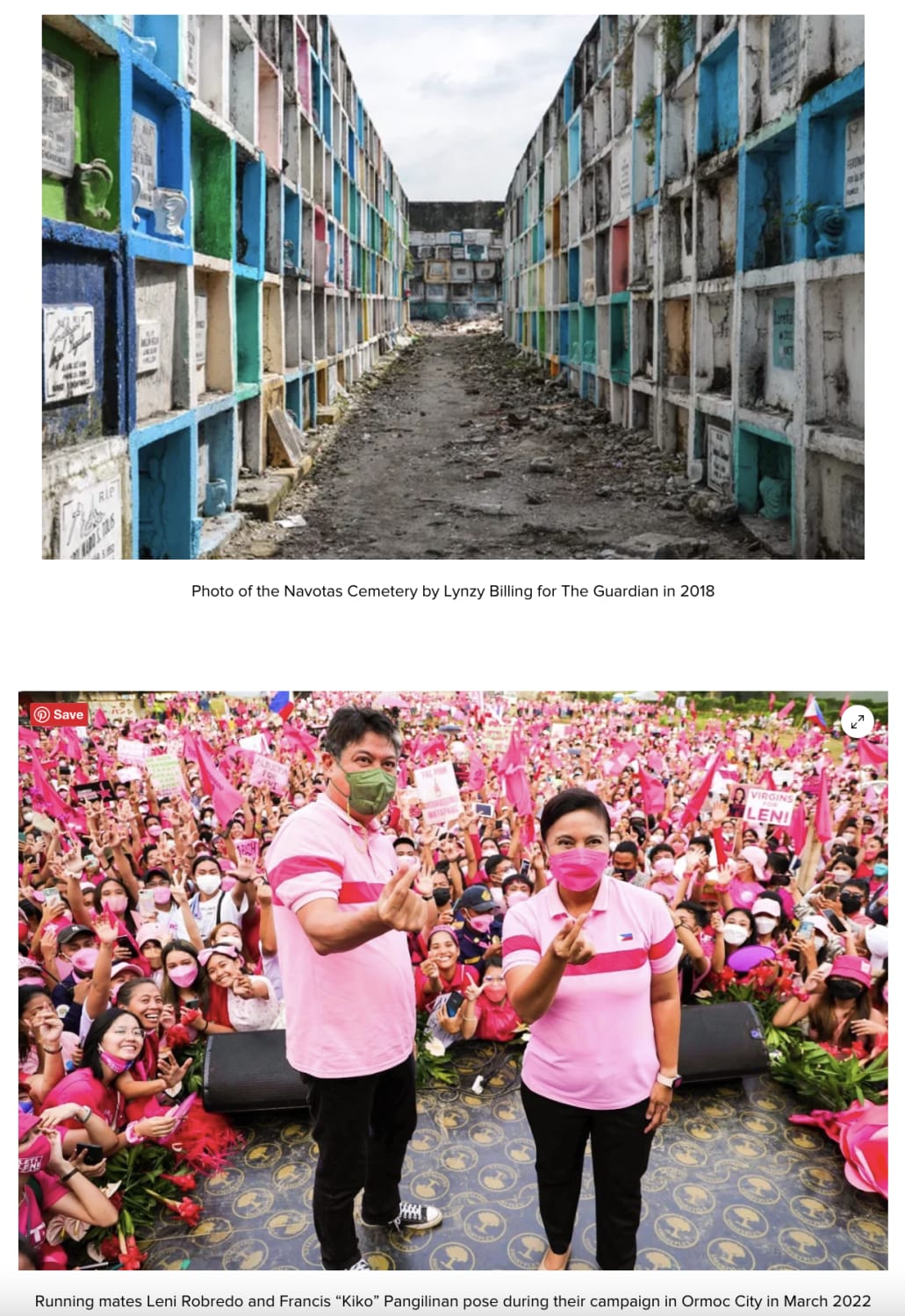

Last month, a photograph showing Robredo and Pangilinan posing with their campaign sign inside a cemetery was circulated on social media. Bongbong’s supporters mocked the pair for their intellect.

However, tsek.ph’s partner FactRakers - a fact-checking initiative by the Journalism Department at the University of the Philippines-Diliman, later proved that the image was doctored.

A reverse image search shows the original photograph of the pair was taken at their campaign in Ormoc City on Mar 29. As for the photograph of the cemetery, FactRakers reported it was taken by photographer Lynzy Billing on Mar 23, 2018 and published in an article in The Guardian.

To counter such disinformation, tsek.ph provides a search engine on its website to help Internet users verify information about the elections and candidates. Its homepage also shows a number of frequently recurring topics plagued by disinformation. These include, for example, ill-gotten wealth, martial law, Ferdinand Marcos Jr and Leni Robredo.

“Just one click and, you know, all the disinformation about it comes out,” said Khan.

According to her, digital disinformation in the Philippines has tripled in the past three years. For fact-checkers - whose task is to detect and correct false information before disseminating it back online - Khan described their work as a “David and Goliath fight”.

“We're just a little entity and there's this big, enormous machine spreading disinformation. But we feel that at least, we are educating people and getting them to have that fact-checking state of mind,” she added.

Apart from fact-checking, tsek.ph also operates tip lines to allow citizens to report potential false news they have come across on digital platforms.

WIKIPEDIA AND EDITED HISTORY DURING THE ELECTION

In the run-up to the elections next Monday, the Philippine digital sphere has a lot of content about different candidates as well as parts of history that are linked to some of them.

On Wikipedia, a popular open-source online encyclopaedia, articles about the Marcos family have seen a number of edits that are not always factual.

James Joshua Lim, a Wikipedia editor and co-founder of the Wiki Society of the Philippines (WikiSocPH), told CNA that edits to Marcos-related articles have spiked during the 2022 elections.

He has been a Wikipedian since April 2005 and spent the past 17 years promoting the platform for democratic creation and distribution of knowledge, including making sure that Philippines-related content is free from misinformation, which is incorrect information presented as a fact.

“There are spikes between elections. If you think about it, it’s like a suspension bridge. It reached its first crescendo around 2016 with the election of Rodrigo Duterte and the talk about Ferdinand Marcos being buried at Libingan ng mga Bayani,” he said, referring to the Heroes’ Cemetery.

“There was a spike in 2019, which was the midterm election when Imee Marcos - Bongbong’s sister - ran and won a seat in the Philippine Senate. Then now, we’re seeing it again in 2022,” he added.

The presidency of Bongbong’s father began democratically in 1965 before he decided to place the entire country under martial law in September 1972 “to save the Republic and reform our society”.

His order resulted in at least 11,103 victims of human rights violations under his regime, according to the local Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission.

Related:

According to Lim, articles about the late president have recorded multiple edits to remove “unsavoury” information about his regime, including terms such as “kleptocrat” and parts about the controversial martial law era.

“On the one hand, you have the wholesale removal of information from articles. On the other hand, you have people rewriting the content to make it sound like ‘Oh, it's not that bad’,” Lim observed.

“We have a responsibility to make sure that what we're serving is truthful and accurate. That's why we keep monitoring these articles.”

To fight disinformation, various projects have been created to fill a gap in the educational system, which many believe has failed to educate Filipinos about their recent history.

A particular chapter that has come under disinformation is the martial law era under the late president Marcos’ rule.

“It's very important to know the past so that we’ll know why we’re in this current situation, why we have these kinds of problems in our democracy, our economy and our political institutions. Because without knowing where we came from, we won't be able to know what we ought to do,” said Miguel Paolo Rivera, director of the Martial Law Museum.

It is a digital museum that exhibits resources related to martial law for the general public. It also offers a comprehensive online learning resource for educators to teach the values of democracy, human rights and freedom to Filipino students.

“A lot of young Filipinos are not very aware of what happened during the martial law regime. Not only are they not aware of what happened but they've also been fed a lot of misinformation about what happened then and its effects on the Philippines now,” the director explained.

With just a few days of campaigning left before the May 9 presidential election, he hopes the museum would be able to serve as “an approachable and reliable academic source for the general public” amid disinformation that has deceived and misled Filipinos.

“Now we're playing sort of a catch-up game. But I think we're getting there.”

Additional reporting by Aiah Fernandez.