Who is Jerald Low, Singapore’s own ‘Tinder swindler’?

The man who confused victims, police and lawyers alike.

- He pulled in more than 10 victims over four years. Their losses amounted to more than S$150,000.

- He lied to police to delay his case and even made his then boyfriend take the rap for him.

- Victims said they were swept along by his show of wealth; his lawyer calls it ‘one of the most complicated cases’ investigators have seen.

SINGAPORE: Jerald Low is a scammer. But unlike typical fraudsters, he does not care if you know his real name or face. In fact, that is the point of his modus operandi.

“He’s somebody who’s sitting in front of you, speaking, breathing,” said deputy public prosecutor Leong Wing Tuck. “(In) a lot of online scams, you don’t know who’s actually behind it. But Jerald’s different.

“He’s a confidence trickster.”

He got more than 10 victims to trust him, one of whom lost about S$100,000 as a result. He has been anything from an ex-classmate eager to reconnect, an ambitious boss, even a promising match from a dating app.

EXPLORE CNA’S SCAMS MICROSITE: Scammers exposed: Investigating Asia-based scams targetting victims around the world

The law took four years to catch up with him. But when he was charged, he was so convincing he was able to get someone to take the rap for him and sent the police on a wild goose chase.

Who really is this person? What makes him tick? And even if he bared his soul on the CNA series, Catching A Scammer, would you believe him?

HEIR TO A FORTUNE

It all started in 2018, when a property agent from ERA Realty Network received a call from a friend who had a prospective buyer to introduce.

A Singaporean with a “very rich” Korean father, and a fat inheritance coming in, wanted to build a collection of trophy properties and had a budget of S$20 million per house.

His name was Jerald Low. He was 24 and looked nothing like a billionaire. But that was not what raised suspicion.

As ERA’s key executive officer Eugene Lim said, in his 30 years of experience in property, even the richest man would negotiate. Low, however, did not bat an eyelid. After each viewing, he immediately paid a down payment, whether it was S$55,000 or S$858,800.

In three days, his purchases amounted to more than S$140 million, in places from Bishan to prime districts like Orchard Road and Grange Road.

This was “extremely” out of the ordinary, and not only because of his age. “Based on the address listed on his NRIC, he was actually residing in a HDB flat,” said Lim.

A background check on him came up clean. He was not on the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s watch list, nor that of the United Nations Security Council. His father’s name, which he gave, also checked out — indeed a wealthy Korean.

But all the cheques Low issued turned out to be duds. When pressed, he claimed there was a delay in receiving his inheritance. “(It) dragged on for a while … so that was the end of the transactions,” said Lim.

But the properties were not what Low was after.

He wanted the selfies he had taken in those fancy penthouses and the legal papers showing he had made down payments and was ready to buy them — ammunition to fool other people in the next stage of his scam.

A BUSINESS PARTNER

In September 2018, Low reached out to a secondary school classmate, Terrence Chew, via Facebook. Chew remembered him as a “very quiet person”. “One thing’s for sure, he didn’t cause any trouble in school,” said the 28-year-old.

Low sent Chew a private message, showing interest in his job selling lifestyle products in a multi-level marketing firm. “I see that you’re doing well, and I was wanting to ask, can I join you?” read one of Low’s texts.

They met up, and it seemed to Chew that Low was keen on learning as much as he could. “He was attentive and seemed like he really wanted to do this as a sideline,” said Chew.

Over the next few days, Low gave his friend every reason to believe in him. First, he told Chew that his parents and relatives were keen to join the network — and the more people joined, the more Chew would earn.

“He told me … (there were) from two people to four people, slowly up to, I think, over 15 people who said they wanted to join him,” said Chew.

This is where the selfies came in.

Listen: Who is the real Jerald Low?

Over meals, Low shared photos of himself with posh cars and in the various properties he claimed to have bought. He said he had millions in his bank account and struck Chew as being a “capable” person.

“I was thinking … he’s someone who’s very important to me right now,” said Chew.

So when Low came to him a week later with a business proposition — a bubble tea business called Fitness Tea — it did not take much for him to say yes. Chew was also a fitness instructor back then.

Fitness Tea was registered with the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority in no time, under both their names.

The first thing Low did was to sign contracts for six mobile lines, bundled with the latest phone models — using Chew’s identity card number.

“He said that he’d use the company’s account to pay these phone bills,” said Chew. “I was too naive, so I believed him.”

Low kept the phones for them to be “configured to the company line”.

But then he wrote cheques for down payments on six offices for the business. That was when Chew started becoming suspicious. “We were setting up a bubble tea company,” he said. “Why’d you want so many offices to run one small shop?”

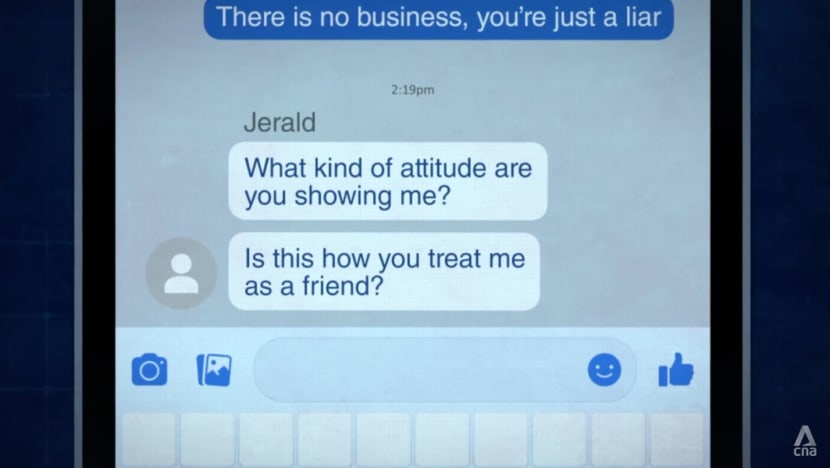

To stave off the questions, Low offered him a salary of S$10,000 a month. But the cheque never came. He confronted Low, who laid a guilt trip on him about being suspicious.

Low eventually took Chew’s name off the business and dropped off the radar.

Chew proceeded to terminate all the mobile lines, to stop chalking up any losses on phone bills. But the early termination fees alone cost him around S$10,000.

He reported Low to the police.

A BOSS AND A FIANCE

Low was ready with “pre-planned initiatives” before he defrauded his victims, said Ho Cher Hin, the officer in charge of the commercial crime squad in the Central Police Division.

“You can see that from the way he started off by registering the company … signing up for mobile lines, (placing) an advertisement (of a job vacancy), printing name cards,” said Ho. “People would think that this person is really someone.”

In October 2018, a month after Fitness Tea was formed, Low hired its first employee, “Jenna”, who also recommended her brother for a job. Their father, a Mr Lim, shared their story with CNA.

“(My daughter) showed me his name card … We found that his registration address — everything — was in order, and there was nothing wrong,” he said.

The letter of appointment that his son showed him also seemed “appropriate”, with the number of days of leave and transport allowance indicated clearly.

But the first suspicious signs appeared during Jenna’s first few days: She was asked to sign up for mobile lines for the company. She was told reimbursement for any purchase she made would be at the end of the month.

Despite her father’s concerns, she did not leave the company as Low had informed her that she was being promoted from administrator to manager, said Mr Lim.

She also told her parents she was going to marry Low, who already had the legal papers showing that he had put a down payment on a housing unit.

“He promised my daughter he’d make her a wealthy lady,” Mr Lim recalled. “They’d have a good life, have maids serving (them) … and (she’d have) no need to work — (she) could enjoy (her) life.”

Mr Lim managed to stop her in time, but she got depressed and, shortly afterwards, was treated at the Institute of Mental Health for a relapse of bipolar disorder.

Low absconded with the phones from the mobile line contracts, and she incurred bills amounting to S$6,405.57. He also obtained pictures of her brother’s identity card and driving licence and used them to rent vehicles.

Then he moved onto his next victim.

WEB OF LIES CONTINUES

Low met “Sam” through a dating app.

Each time they met, he turned up in a different posh vehicle to give the impression that he was very well-to-do, said Ho. These cars were rented using Mr Lim’s son’s licence — Low himself did not have one.

He even drove Sam to a condominium unit that he said was one of his property investments. He also logged into a bank account and showed Sam the S$1 million he said was his inheritance.

Low had discovered that Sam was keen to supplement his income, according to Ashley Karen Chong, a senior investigation officer in the Tanglin Police Division. So after setting the stage, Low struck.

He told Sam he wanted to buy more properties but, to do so, had to let some of his existing ones go. He offered Sam a “special price”.

“(Sam) agreed on the spot and transferred … S$4,200 as a deposit,” said Chong. “He didn’t go and find out whether the condo belonged to Jerald. It was based on trust.”

Low also convinced Sam that the investments Sam was making were unprofitable and persuaded him to transfer his funds to a Singapore Exchange (SGX) account Low shared with his mother. But as the “account” was private, only Low could see it.

Again, Sam trusted Low — to the point of borrowing money from banks and legal moneylenders to invest more. Low promised to pay the lenders back, but via Sam’s bank account, since the loans were made in Sam’s name.

Because of that, Sam handed over his debit card and bank token.

In a statement to CNA, the SGX Group clarified that “an ‘SGX account’ doesn’t exist at all”.

“Singapore Exchange offers Central Depository (CDP) accounts to investors,” said a spokesperson. “The CDP account is a depository account for shares and other equities and certain government bonds.

“To buy or sell any of your holdings, you have to go through a brokerage or a bank, depending on the type of asset. It’s important to note that SGX and CDP won’t ask anyone for deposits for any investment.”

In December 2018, the moneylenders turned up at Sam’s home. He also discovered that his bank balance had been wiped out. Confronting Low, who was on holiday in London, brought nothing but accusations that Sam was “spoiling his trip”.

By the time Sam filed a police report in January 2019, his losses amounted to S$100,000, including money he had loaned to Low for his business, Fitness Tea. He had also been persuaded to sign up for mobile lines.

ALLEGATIONS OF ABUSE

In February 2019, police charged Low after investigations into the earlier cheating cases concluded.

Chew, for one, felt that the investigation process was “very slow”. There were other victims who filed police reports, however, and with financial investigations, “a lot of evidence has to be individually assessed”, said Ho.

As much as we want justice to be served as soon as possible … it’s about being fair. It could be possible (that) if you don’t look at the evidence in totality, (you) charge the wrong person.”

At that time, the prosecution did not object to bail, and Low’s mother put up the S$15,000 bail for him. But while he was out on bail, he committed only more scams.

Fresh police reports came in — different versions of the same story — and triggered further investigations.

It was “by far one of the most complicated cases that we’ve dealt with”, said Gino Hardial Singh, Low’s lawyer under the Criminal Legal Aid Scheme.

The police took more than a year, until September 2020, to charge Low with more offences.

Then the unthinkable happened: Low himself filed a police report, claiming that his partner had physically and verbally abused him and had forced him into crime.

He turned up for police interviews crying in a way that was “hard to doubt”, said Ho. “He had this eye contact with us that looked so convincing.”

This partner, when interviewed, corroborated Low’s claims. The investigation process had to restart as police poured nine months of work into re-interviewing subjects and reviewing evidence, said Ho.

In that time, Low reported his partner to the police twice more in a bid to appear more convincing and to delay the court proceedings.

The reports all turned out to be false. His partner had repeatedly lied to the police to support Low’s claims.

Low confessed in June last year. In total, police brought 52 charges against him, involving more than 10 victims whose losses amounted to S$150,000 over four years.

On March 16, he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 67 months in jail. It was the end of a long saga. “It was a relief to see closure,” said Ho.

WATCH: Catching Singapore’s very own ‘Tinder swindler’ (46:03)

THE REAL JERALD LOW?

But what motivated Low? Why is he the way he is? His back story, which he shared from inside Changi Prison, included a “horrible” childhood and being “looked down (on) since young”.

“My parents are divorced,” said the 28-year-old, whose mother and grandmother brought him up. “(At) school, friends laughed at me (for having) no father.”

He said that in 2018, he wanted to get rich quickly because his family could not pay his ailing grandmother’s hospital bills. His mum, too, was diagnosed with cancer.

“I just wanted to get the money and then pay off whatever debts I had,” he said.

So he turned to Google. “One of the websites (I found) had a particular technique of teaching you how to scam,” he said. “This only works with your close friends and relatives.”

Without many friends, he tried to appear rich to attract those who were not close to him.

The idea — which he said he read about in the papers — was to get people to sign up for mobile lines and sell the phones for profit.

“I know it’s their hard-earned money,” he said. “But at that point … I didn’t think (it) through.”

He said he regretted his decisions, especially because of the hurt he had caused his mother. She had attended his court hearing and visited him in prison every month. She died three months after he began serving his sentence, and he felt like he “lost everything”.

To the victims he hurt, he said he was “truly sorry”.

“Whatever I’ve done … can never be undone,” he acknowledged. “I do hope that I’ll just prove to all the victims and all those persons around me … I’m a changed person.”

Watch this episode of Catching A Scammer here.