Save money, be cool: Indonesian project shows how ‘cool’ roofs can help Asia beat the heat

It is a special product but easy to use and more climate-friendly than air-con. An Indonesian architecture lecturer tells the programme Money Mind how she hopes to expand the reach of this heat-reducing roof coating.

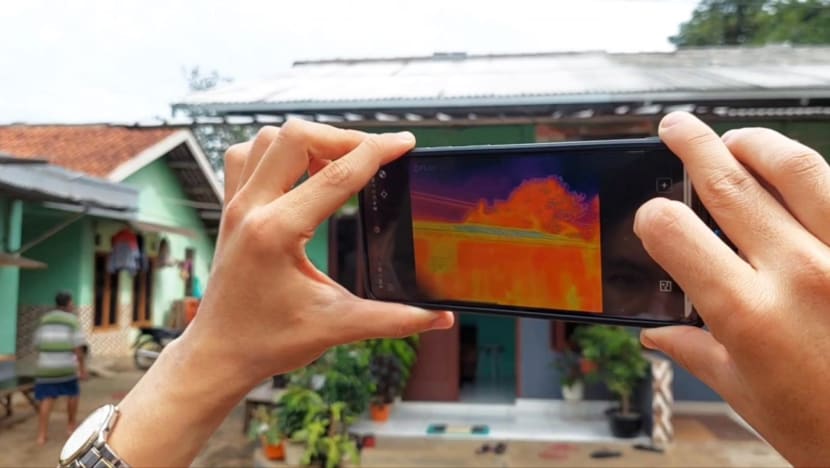

No air-conditioning? That may not be a problem with a “cool” roof. (Photo: BeCool Indonesia)

BANDUNG, Indonesia: In Asia, a region that could see more heatwaves like the one last month, there is a low-cost, sustainable way to make temperatures more bearable for people in cities.

“Cool” roofs have a special coating applied to reflect sunlight and reduce the amount of heat absorbed by a building. The result is lower indoor temperatures.

In Southeast Asia’s largest country, a project championed by architecture lecturer Beta Paramita could show a way to scale this climate-friendly solution in a heating world.

It is mainly commercial and office buildings that can afford air-conditioning in Indonesia, while schools mostly do not have air-con and neither do 80 per cent of homes, said Beta, the project manager of Cool Roofs Indonesia.

Related stories:

Last year, Cool Roofs Indonesia won the Million Cool Roofs Challenge — a global competition that aims to scale the use of cool roofs in developing countries suffering from heat stress — and received a US$750,000 (S$1 million) grant.

This was after the project won a US$125,000 grant as one of 10 finalists in the 2019 challenge, with other finalists from countries such as Bangladesh, the Philippines and South Africa.

Initially, the project covered more residences, said Beta. But they tend to be small and have higher levels of activity at night than in the day when people are out. So the team began targeting educational and religious institutions.

“From 7am until 2pm or 4pm, the kids, especially elementary school students, (are) inside the building,” Beta said. If the weather is too hot, the pupils cannot concentrate and perform worse in cognitive tests in the afternoon than in the morning, she added.

Indoor heat is also a problem that affects a higher proportion of women in Indonesia, as some are at home taking care of the children and cooking, she said.

A DROP FROM 40 TO 29 DEGREES

Tangerang, an industrial hub near Jakarta and home to the Soekarno-Hatta International Airport, was the first city to join the pilot project and offered 15,000 square metres of roof space, said Beta, an assistant professor in Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia’s (UPI)’s architecture department.

Other cities the project has reached include Jambi, Palembang, Semarang and Pontianak. “We try to spread this product to the hot cities,” said Beta, who is based in Bandung in West Java.

Besides climate change, there is another reason for heat build-up in urbanised areas. Known as the urban heat-island effect, it is caused by hot exhaust from air-conditioners and vehicles, buildings storing heat in the day and releasing it at night and other reasons.

Since winning the challenge, Cool Roofs Indonesia has deployed its technology on the roofs of more than 40 public and community buildings, with more in the pipeline. It has seen some dramatic results so far.

In one industrial building covering 5,000 sq m, the indoor temperature dropped from 40 degrees Celsius to around 29 degrees Celsius.

In other places like schools, the temperature drop could be smaller. The difference could be due to building type, materials and design, said Beta and another member of Cool Roofs Indonesia, Ravi Srinivasan of the University of Florida.

“The surface is almost three to four degrees lower. … Room temperature (could be) just one (to) one and a half (degrees lower), but it’s (still) significantly better,” said Palembang-based Sandra Eka Febrina, an architecture lecturer at Universitas Indo Global Mandiri.

She got involved in Cool Roofs Indonesia last year and mentored students to introduce cool roofs to the community.

Even in Bandung, which is more than 700 m above sea level and relatively cooler than some other Indonesian cities, cool roofs have made a difference.

At the office of Aaksen Responsible Aarchitecture, managing partner Azzahra Dartaman said the coating reduced the indoor temperature from around 32 degrees Celsius to 25 to 27 degrees Celsius.

“The benefit is that we don’t use the air-conditioner,” she told the programme Money Mind.

WATCH: Low-tech, low-cost solutions to keeping cool in Indonesia (6:04)

While Aaksen did not calculate the drop in its electricity bill, she said there are also savings from running the fans less often: During “midday” hours only, instead of “almost all the time” previously.

THE AMERICAN LINK

Cool Roofs Indonesia’s water-based product is simple to apply, said Beta. It consists of a primer, or undercoat, that dries in 30 minutes and a coating that reflects 84 per cent of solar energy and radiates 90 per cent of absorbed heat.

After it is weathered, the levels drop to 77 per cent and 88 per cent respectively.

The product is a version of a similar paint patented in the United States by the University of Florida and two companies called Milenium Solutions USA and WinBuild Inc, said Srinivasan, who met Beta in 2018 when he was in Bandung giving a speech on net-zero energy buildings.

They kept in touch, and his past experience working on a US Department of Energy project on cool paints in South Africa was useful when they worked on proposals for the Million Cool Roofs Challenge.

Although not a competition requirement, the primer and coating have been manufactured locally since 2019 — at a factory set up at Beta’s university. “My director (at UPI) gave me the land; I never thought it’d be a factory,” she said.

The decision to manufacture locally was a collective one, said Srinivasan, the director of the UrbSys Lab at the University of Florida’s M E Rinker Sr School of Construction Management.

“Manufacturing in the US is expensive, and then … you’d have to ship it to Indonesia.”

Besides reducing costs, the second reason was to provide employment in Indonesia.

Beta recalled asking Milenium Solutions if it wanted an industry partner in Indonesia to make the primer and coating but was told the firm preferred collaborating with a university for the research potential.

The facility at UPI can churn out 4,000 kilogrammes of primer and coating daily. Two more facilities will be set up this year with university partners in Banjarmasin, South Kalimantan, and Lampung, Sumatra, she said.

The project will set aside 10 per cent of production for corporate social responsibility purposes, which would cover about 14,400 sq m annually, she shared. The product is free for public buildings like schools, orphanages and religious institutions, she said.

For commercial customers, the product, marketed under the BeCool brand, is still cheaper than other brands on the market, she added. “We just want the product (to be widely adopted) in Indonesia and … at an affordable price.”

A set of 20 kg of primer and 20 kg of coating costs 2.73 million rupiah (S$247), which can cover 120 to 160 sq m in area, depending on the absorbency of the roof material.

A low-cost housing unit in Indonesia — at an average of 36 sq m — with a clay roof would need 13 kg of primer and coating each, estimated Beta.

With the US$750,000 prize money to be disbursed in five tranches over three years, the plan is also to set up a national laboratory to study the properties of building materials, such as how much heat they reflect and absorb, she said.

AIR CIRCULATION, BUILDING DESIGN ALSO MATTER

Since the Money Mind video appeared on YouTube, more people have visited BeCool’s website and contacted the manufacturer, which is a company registered under UPI, she said.

Purchases in Indonesia are usually made via WhatsApp, and the company also receives requests to distribute the product overseas and is looking into it.

Although the BeCool coating has been well received, Beta has had some less positive feedback from journalists who said indoor temperatures have not dropped as much as desired.

She cautioned that cool roofs may not be a surefire way to significantly reduce indoor temperatures as other factors are also at play, such as the building’s design, orientation and quality of air circulation.

“Every house has got different problems,” she said. “Some buildings aren’t well designed.”

She recalled visiting an architect’s office whose indoor temperature dropped “just” 2 degrees Celsius despite a drop of 15 degrees Celsius on the outside surface. The problem was a lack of air circulation, Beta said.

I said to put exhaust fans in the west and east areas. After that, everything was solved. They (didn’t) need (to install) air-con.”

Beta, who has researched the urban heat-island effect, said that although the project is a platform for education and the main objective of cool roofs is to mitigate global warming, it is easier to get the economic benefits across to people.

“When you use cool roof coating, you’ll be reducing the use of fans,” she might explain. Or “setting your air-con not at 18 but at 25 degrees Celsius will mean reducing your electricity bill”.

Other countries that have tried cool paint include Singapore. In 2021, the Housing and Development Board and Tampines Town Council announced a large-scale pilot project involving about 130 blocks, with the aim of reducing the ambient temperature by up to 2 degrees Celsius.

The project, including its review, is expected to be completed by next year.

Both developed and developing countries as well as high- and low-income communities can adopt cool roofs, said Srinivasan. But the technology would benefit lower-income groups more.

“In the US, there are certain portions of communities spending about 20 to 30 per cent of their income on paying electricity bills,” he cited as an example. With this technology, they could save on air-con or fans and allocate the money for food.

Watch this segment of Money Mind here. New episodes every Saturday at 10.30pm.

Read this story in Bahasa Indonesia here.

Read this story in Bahasa Melayu here.