Commentary: Tighter enforcement not enough to prevent workplace fatalities in Singapore

The migrant worker who died in a Tanjong Pagar structure collapse calls attention to a growing number of workplace fatalities in Singapore. NUS’ Goh Yang Miang weighs in on why greater awareness and more safety measures haven’t seemed to take effect.

SCDF officers at the site of the collapsed building structure at Bernam Street in Tanjong Pagar on Jun 15, 2023. (Photo: CNA/Syamil Sapari)

SINGAPORE: The death of migrant worker Vinoth Kumar in a structure collapse at a Tanjong Pagar worksite reignites concern about a growing list of workplace fatalities in Singapore.

Just three days before that incident, a worker died after being electrocuted while installing rooftop solar panels.

There were 46 workplace deaths in 2022, the highest number since 2016. This triggered the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) to implement a heightened safety period in September 2022, which tightened enforcement and introduced fresh measures.

Serious lapses would result in senior management being held accountable and temporary bans on employing new foreign workers.

The heightened safety period was initially planned for six months but was extended for three additional months, before ending on May 31.

MOM reported a significant decline in workplace fatality rate during the period, but the major injury rate worsened. New safety requirements were announced following the end of the heightened safety period, such as mandatory video surveillance systems for construction sites with a project value of S$5 million (US$3.7 million) or more from June 2024 onwards.

Unfortunately, workplace injuries and deaths have occurred since the end of the heightened safety period. The structural collapse at Tanjong Pagar attracted significant attention due to the scale of the accident and its impact on public safety.

Why haven’t greater awareness and new enforcement measures put an end to workplace accidents?

SHIFTING THE BURDEN

The recent fatalities are signs that the effects of the heightened safety period were short-lived. After all, tight enforcement is costly and unsustainable for the government and the industry.

Emphasis on enforcement can also lead to stakeholders shifting the burden of ensuring workers’ safety to the authorities, resulting in degradation of safety culture within the organisation.

It is crucial for companies to focus on the fundamental problems of workplace fatalities, including inadequate leadership commitment, a lack of double-loop learning where managers reflect on the deeper causes of an accident, and insufficient worker participation and consultation.

Many of the additional measures following the heightened safety period aim to resolve these issues by encouraging industry ownership of worker safety. But their effectiveness depends on how they are implemented.

Mandatory safety measures can quickly become tick-box exercises, where the industry implements the measures superficially without meeting the intent of the requirements.

SHARING THE BURDEN

Singapore has been promoting soft interventions such as encouraging the industry to self-regulate and report their workplace safety and health (WSH) performance, and recognising companies with good WSH standards.

While these soft interventions are largely driven by MOM and the WSH Council, there are other forces nudging companies in this direction.

With the growing concerns about climate change and business mismanagement, the corporate world appears to have accepted environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting as a norm.

Two of the fundamental principles of ESG reporting are transparency and stakeholder engagement. Organisations must report their safety management approach and their performance, so that stakeholders can make decisions regarding their investments, influencing the companies’ priorities.

In recent years, the Singapore Exchange has started requiring ESG or sustainability reporting. Publicly listed companies need to report WSH indicators such as the number of fatalities and recordable injuries.

ESG requirements could drive market behaviour, where publicly listed companies will focus more on workplace safety and exert their influence through the supply chain.

But this might all be in theory. I discussed the potential impact of SGX’s sustainability report on companies’ safety records with an ESG expert last year. The expert bluntly shared that WSH is a tiny area of concern within ESG, and there would not be much interest from the corporate world.

I also attended an ESG seminar and realised that the speakers and participants were focused on the environmental aspect and appeared oblivious to WSH issues. More needs to be done in this space.

BUILDING A STRONG SAFETY CULTURE

Engaging stakeholders through ESG reporting or other information sharing is not foolproof. Researchers have suggested that soft interventions should supplement hard regulations.

MOM and WSH Council have done much in that respect over the years, with the former stepping up companies’ accountability for workplace accidents, and the latter providing comprehensive guidelines and timely WSH alerts.

Nevertheless, to effectively engage more organisations in building a safety culture, there is a need for more sharing of information.

Since 2018, the WSH Act has empowered the Manpower Ministry to publish learning reports to share significant lessons learnt following workplace accidents or diseases. Unlike the accident alerts disseminated by the WSH Council, learning reports are more in-depth and are not admissible in court.

However, to date, there are only two learning reports published. More can be shared to ensure that companies can improve from the failures of others. In addition, findings from WSH prosecution cases that had been thoroughly debated in court should be captured and disseminated.

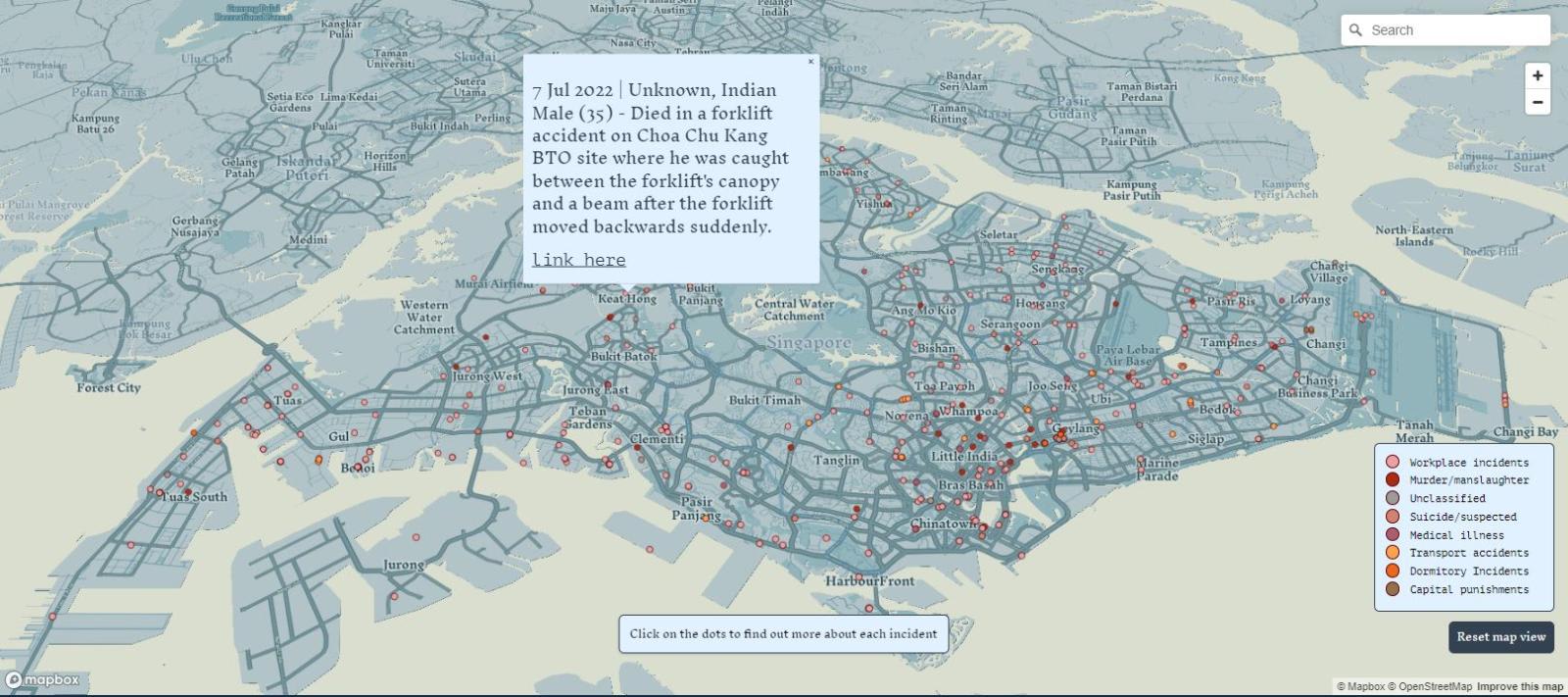

Furthermore, more WSH data should be shared with stakeholders. For example, an anonymous team of activists developed the Migrant Death Map (an interactive map capturing migrant worker deaths across Singapore) based on public sources. From an ecosystem point of view, more open access to WSH datasets and cases allows for deeper analysis, which can help facilitate the work of civil society groups.

Similarly, educational institutions could use this information to groom the next generation of managers to be more committed to WSH. Universities and technology start-ups can also use the data to innovate and develop possible solutions to WSH problems.

The heightened safety period was necessary to arrest the spate of fatalities in 2022. To improve and sustain a safety culture, a more comprehensive range of stakeholders has to be engaged and empowered through information sharing.

Dr Goh Yang Miang is Associate Professor with the Safety and Resilience Research Unit (SaRRU) at the Department of the Built Environment, National University of Singapore, where he is also the Director of the Centre for Project and Facilities Management.