Commentary: The US may win some trade battles in Southeast Asia but lose the war

Southeast Asian countries have little choice but to continue engaging US officials now, but the US risks driving them into the arms of others in the long run, says Kevin Chen from the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies.

US President Donald Trump walks after disembarking Marine One as he arrives at the White House in Washington, DC, US on Jul 6, 2025. (Photo: Reuters/Ken Cedeno)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Three suspense-filled months after his self-declared Liberation Day, US President Donald Trump announced a new series of tariffs that may baffle Southeast Asian governments.

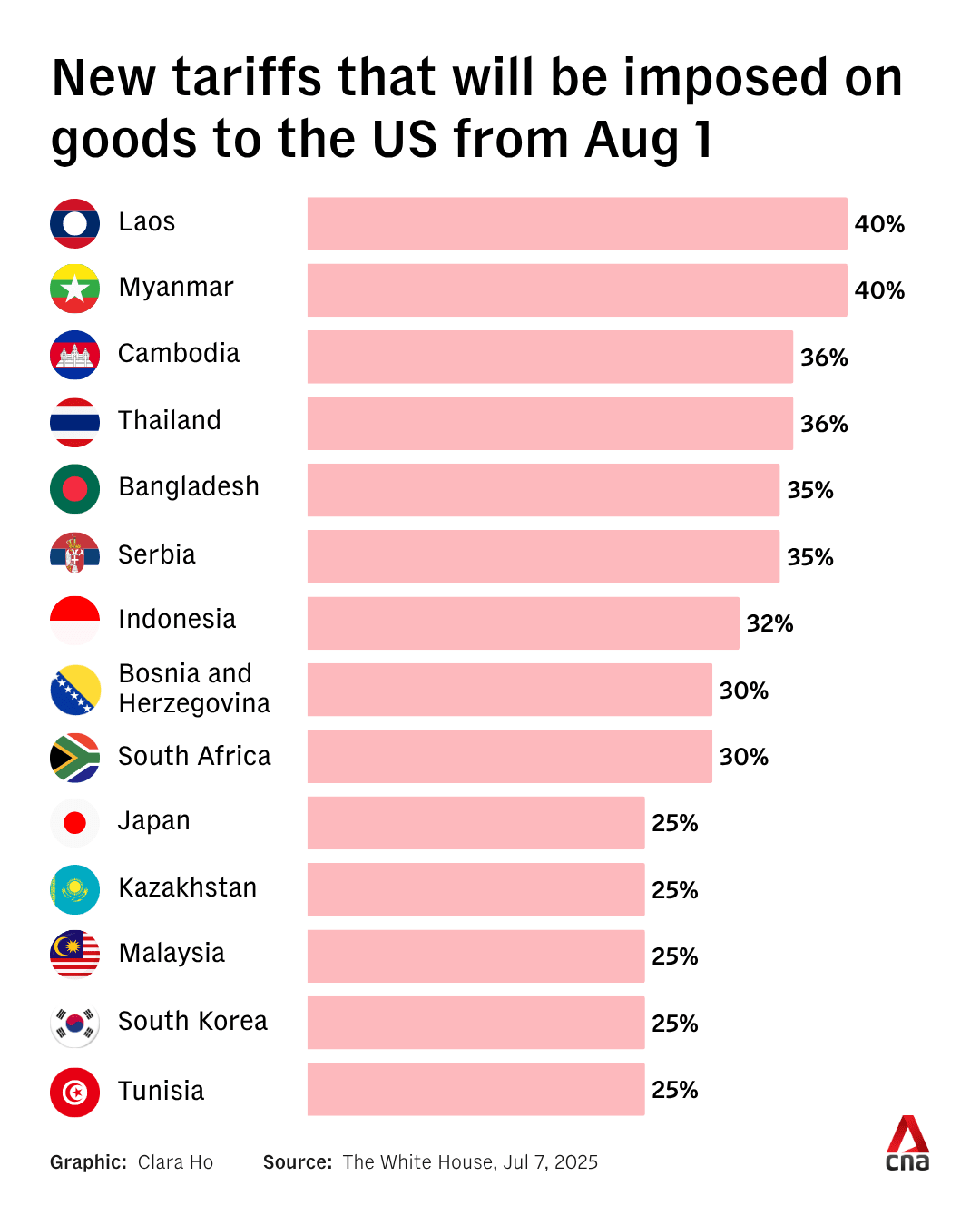

On Monday (Jul 7), Mr Trump repeated grievances about “unsustainable trade deficits” in letters to 14 countries, of which six were in Southeast Asia. In what appears to be a shot across the bow instead of an escalation, the latest rates roughly coincided with those announced in April.

Officials from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand recently expressed hope that they were close to trade deals with Washington. Yet their tariff rates are set to be unchanged, with Malaysia’s even increasing by a percentage point to 25 per cent.

It raises concerns that their proposals are not enough for Mr Trump, and what better negotiating terms they can offer before the extended deadline of Aug 1.

Cambodia was an outlier in this first batch, with its tariff rate going down from 49 per cent to 36 per cent. Cambodian media recently reported that the countries had agreed on a draft joint statement about a trade agreement framework, though Washington has not supported this with an official announcement.

To date, Vietnam remains the only Southeast Asian country with which the US announced a trade deal, cutting its tariff rate from 40 per cent to 20 per cent on paper with details yet unclear.

It is easy to obsess over the specific numbers in the letters, but more important are the implications behind them. As Washington’s goal posts appear to shift, regional governments will be forced to play along – for now.

TARIFFS AS NEGOTIATING TOOLS

Mr Trump should be given some credit for recognising the utility of tariffs as being “good for negotiation”, as he remarked in a July 2024 interview with Bloomberg Businessweek.

Presciently, he said that “[countries] would do anything” to get him to stop or lower his tariffs, if they are unwilling to lose the lucrative US market.

After all, the US is the biggest export destination for economies such as Vietnam and Thailand. High tariff rates would hurt the competitiveness of their exports, with economists in Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand warning that tariffs could shave off up to one percentage point off economic growth estimates for 2025.

As such, Southeast Asian governments have been proactive in engaging Washington to secure lower tariff rates. Some made last-minute attempts to increase their offers to Washington.

Indonesia announced a US$34 billion pact to increase imports of fuel and raise Indonesian investments in the US. Thailand initially proposed to balance its trade with the US over a decade, then upped the ante to seven to eight years in a Hail Mary proposal last week.

It is still unclear whether all these efforts were for naught.

SHIFTING GOAL POSTS

Yet, a more poignant observation concerns the increasingly political nature of Mr Trump’s goals.

Mr Trump has outlined at least three economic purposes for the levies: to raise government revenue, to balance the US trade deficit and to attract manufacturing investments. Southeast Asia governments have responded accordingly, their proposals often involving lower trade barriers, balancing their trade surplus with the US and investing in US energy, agriculture and manufacturing.

However, the goals have shifted in subtle, but important ways, influenced by deepening US-China competition. Tariffs are no longer just a trade tool, but include demands to join the US in confronting Chinese practices and influence.

One such practice is illegal trans-shipping, which was at the heart of Mr Trump’s first trade war with China in 2018. At the time, Chinese manufacturers began to leverage Southeast Asian countries to hide the origins of their finished products for export to the US, a trend that was noticed even during the Biden administration.

Demands to crack down on trans-shipping feature prominently in the US-Vietnam deal. Yet, even as countries such as Malaysia and Thailand pledged to more strictly enforce rules of origin, it remains to be seen whether Washington will be satisfied with their promises or if it will consider goods with any link to China a transgression.

DEFINITION OF “ANTI-AMERICAN” POLICIES

Mr Trump also set off alarm bells in regional capitals with his announcement of an additional 10 per cent tariff on any country “aligned” with the BRICS group of developing countries. This could not just impact Indonesia, which joined the grouping as a full member in January, but also Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam, which are partner countries.

While one US official suggested that the tariff will only be imposed against “anti-American” policies, that is unlikely to reassure skittish observers. If anything, it will raise serious questions about the definition of “anti-American”.

Southeast Asian governments have operated on the assumption that Mr Trump is a dealmaker, and that he can be convinced by economic incentives to back down. However, the truth appears to be much more complicated.

It is one thing for countries to negotiate a trade deal, which typically takes years. Involving politics and security issues, however, complicates an already technical conversation.

Even if countries heed Mr Trump’s call to “build or manufacture product” in the US in exchange for zero tariffs, there is no guarantee that he will not impose more tariffs as part of an effort to confront China.

WINNING BATTLES, BUT LOSING THE WAR

For the moment, countries have little choice but to continue engaging with US trade officials to secure a better deal. But Washington’s tough demands and zero-sum trade approach will push countries away in the long term, diversifying their trade links to avoid over-reliance on the US market.

In the past three months alone, ASEAN countries expanded their trade links with the Gulf Cooperation Council, while agreeing to the third version of their free trade agreement with China. Work is also underway to improve intra-regional trade, which has remained stagnant at roughly 23 per cent since 2000.

The US may win several battles in its quest for concessions via tariffs.

However, it may lose the broader war by driving other countries away, not necessarily into China’s arms, but into a position that is less vulnerable to leverage from Washington.

Kevin Chen is an Associate Research Fellow with the US Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.