analysis East Asia

What does British PM Keir Starmer’s China trip say about Western hedging in a Trump era?

Leaders from Ireland, Canada, Finland - and now the United Kingdom - have visited China within a month as the US rattles the world order. Structural factors limit the scope for deeper cooperation, say analysts.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BEIJING: British Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s visit to China this week is the latest in a growing procession of Western leaders heading to Beijing - a diplomatic rhythm that has quickened as the United States under President Donald Trump rattles the world order.

For many of these capitals, the visits marked their first leader-level trips to China in close to a decade or more, mirroring how Starmer's visit is the first in eight years by a British PM.

The flurry of top-level visits by Ireland, Canada, Finland this month - and now the United Kingdom - reflects a recalibration rather than a reset in China’s relations with Western partners as countries hedge against Washington’s unpredictability, say analysts.

Yet even as dialogue channels open up and low-friction cooperation advances, deeper disputes over trade, security and geopolitics continue to cap the scope for a more fundamental reset, observers say.

“The ceiling for cooperation remains low because the constraints are structural,” Li Yaqi, a researcher at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore, told CNA.

“Expect improved atmospherics and dialogue, but not a wholesale reset in strategic trust.”

JOURNEY TO THE EAST

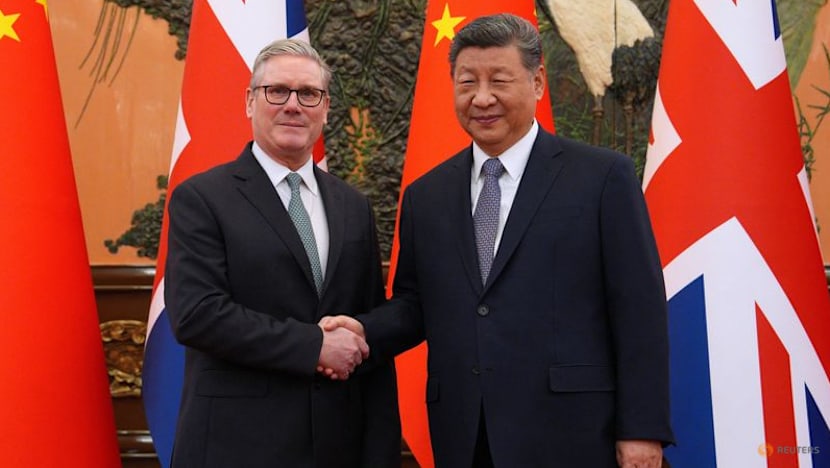

During Starmer's talks with President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People on Thursday (Jan 29), the Chinese leader said China and the UK should work towards a “long-term, stable comprehensive strategic partnership”, calling for deeper dialogue and cooperation at a time of global turbulence, reported Chinese state news agency Xinhua.

As permanent members of the United Nations Security Council and major economies, Xi said the two countries had a responsibility to safeguard stability and turn the “considerable potential” of bilateral cooperation into concrete results, in remarks carried by Xinhua.

The Chinese supremo pointed to expanding cooperation in areas including education, finance and services as well as joint research in artificial intelligence, biosciences and low-carbon technologies, while urging Britain to provide a “fair, just and non-discriminatory” environment for Chinese companies.

He also said Beijing was willing to consider granting unilateral visa-free access to British citizens.

Meanwhile, Starmer described his visit as aimed at forging a “more sophisticated relationship” with China - balancing commercial opportunities with clear-eyed security guardrails. The British PM is accompanied by more than 50 business leaders on the four-day trip that ends Saturday.

“China is a vital player on the global stage and it is vital that we build a more sophisticated relationship where we can identify opportunities to collaborate, but also allow a meaningful dialogue on areas where we disagree,” Starmer said.

Starmer’s trip is the latest in a series of recent top-level visits made by Western leaders to Beijing.

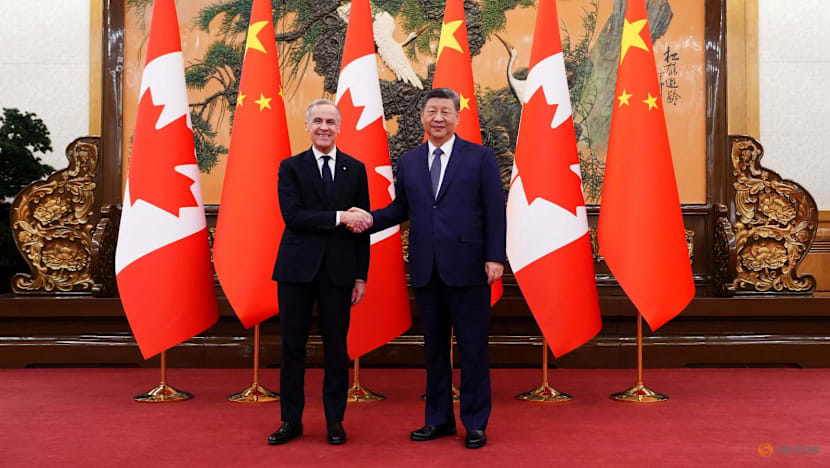

In just this month alone, Beijing has hosted Irish Taoiseach Micheal Martin, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo, with each visit ending a long gap in top-level engagement.

Martin’s visit was the first by an Irish taoiseach since 2012, while Carney’s visit was the first by a Canadian prime minister since 2017. Orpo was the first Finnish prime minister to travel to China since 2017.

In December, French President Emmanuel Macron made his first official visit to China since April 2023, while Spain’s King Felipe VI visited Beijing in November - the first visit by a Spanish monarch to China in 18 years.

And diplomatic traffic is set to continue, with German Chancellor Friedrich Merz reportedly planning his first visit to China later this month, which would mark the first trip by a German chancellor since Olaf Scholz travelled to Beijing in November 2024.

Engagement has been two-way as well. Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng travelled to Europe for the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, while Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Europe twice last year, in June and again in September, as Beijing stepped up outreach to European capitals and EU institutions.

HEDGING IN AN “AMERICA FIRST” ERA

The clustering of visits to China marks a clear uptick in leader-level diplomacy rather than routine exchanges, analysts said.

“What stands out is not just the visits themselves, but the tempo,” said Li from RSIS, noting that the diplomatic push is unfolding alongside persistent trade and technology frictions.

“This suggests leader-level engagement is meant to prevent further hardening of competition, rather than mark a return to routine warmth.”

Li added that European leaders are framing outreach to China as hedging and diversification, while Beijing is packaging cooperation as “stability plus deliverables” to make engagement politically sellable at home.

The result, he said, is a convergence driven less by strategic alignment than by shared incentives to hedge against growing uncertainty in US policy.

Since returning to office a year ago, Trump has revived tariff threats against allies, framed trade in openly transactional terms and rattled European capitals with renewed rhetoric about acquiring Greenland, a Danish autonomous territory.

Earlier this month, he threatened sweeping US tariffs on eight European countries opposed to his push for control over Greenland.

While the US president eventually walked back the threat days later, his comments triggered blunt responses from European leaders, who warned against coercion and questioned Washington’s reliability as a partner.

Friction spilt into public view at the World Economic Forum in Davos this month, where European officials pushed back against Trump’s economic nationalism and warned that renewed trade wars would hurt allies as much as rivals.

Canada, America’s northern neighbour, also struck a pointed note - with Prime Minister Carney winning a standing ovation for his frank assessment of a "rupture" in the US-led, rules-based global order.

Addressing political and financial elites at the forum, Carney said middle powers like Canada, which had prospered through the era of an "American hegemon", needed to realise that a new reality had set in, and that "compliance" would not shelter them from major power aggression.

From Beijing’s vantage point, the visits by leaders from the West are part of a calibrated strategy rather than a reflex to external pressure, analysts said.

From Beijing’s perspective, the outreach is about managing risk, not rekindling trust, Sun Chenghao, a fellow at Tsinghua University’s Center for International Security and Strategy (CISS), told CNA.

“This visit should first be seen as an opportunity to halt the slide and stabilise China-UK relations, rather than a simple reset,” he said, referring to Starmer’s China visit.

Sun, who is head of the US-EU (European Union) programme at CISS, said China is placing Starmer’s trip within “a broader European picture of more frequent and more pragmatic engagement”, testing whether key capitals have room to rebalance without choosing sides.

RECALIBRATION, NOT A RESET

Yet even as diplomatic traffic picks up, analysts have cautioned that the scope for a deeper reset in China-Europe relations remains tightly constrained, with trade frictions, Ukraine and security concerns continuing to set a low ceiling on what renewed engagement can achieve.

The current wave reflects a form of “managed re-engagement”, in which leader-level diplomacy is being used as a stabilisation tool rather than a signal of restored trust, said RSIS’ Li.

“Trade frictions over overcapacity and subsidies will resurface despite warmer optics, and Ukraine remains a persistent trust barrier.”

More fundamentally, Li said, security and technology concerns - including export controls and investment screening - now define the outer boundaries of engagement.

In the recent visits by the UK, Finland, Canada and Ireland, deliverables have largely clustered around low-friction cooperation rather than big strategic bargains.

Starmer’s trip has focused on reopening economic channels and practical law-enforcement coordination, including against people smuggling, alongside discussions on easier visa access.

Orpo’s visit yielded a clean-energy cooperation agreement, while Martin's trip centred on trade promotion and people-to-people links such as education and business engagement.

Carney’s trip secured agreements on a raft of areas from trade to tourism, although he has described them as limited in scope rather than a sweeping deal after coming under pressure from Trump over doing business with China.

Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis and senior fellow at Bruegel, pointed to EU tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles as a reminder that friction has become institutionalised rather than episodic.

China’s stance on Ukraine, alongside European concerns over espionage, human rights and economic coercion, she said, means the relationship is unlikely to move beyond re-engagement.

Sun from CISS expressed similar sentiments. He added that from Beijing’s perspective, the limits are well understood and that Chinese policymakers increasingly distinguish between manageable disputes and structural constraints.

China wants tangible economic outcomes and more predictable political relations to advance in parallel, Sun said.

On the economic side, he noted, priorities include stabilising trade and investment ties by reducing what Beijing sees as discriminatory scrutiny of Chinese firms and improving certainty around market access, particularly in areas such as new energy vehicles, the green transition and financial services.

At the political and strategic level, Sun said China hopes Europe can retain a degree of autonomy in its China policy, rather than being fully shaped by US narratives and tools, while preserving cooperation on global governance issues such as climate change, public health, development finance and AI governance.

Analysts pointed out that despite sustained engagement with Beijing, the EU has found it difficult to hold a unified China position, with internal divisions repeatedly surfacing when Brussels seeks collective action.

The bloc’s two main engagement tracks with Beijing last year underlined this dynamic.

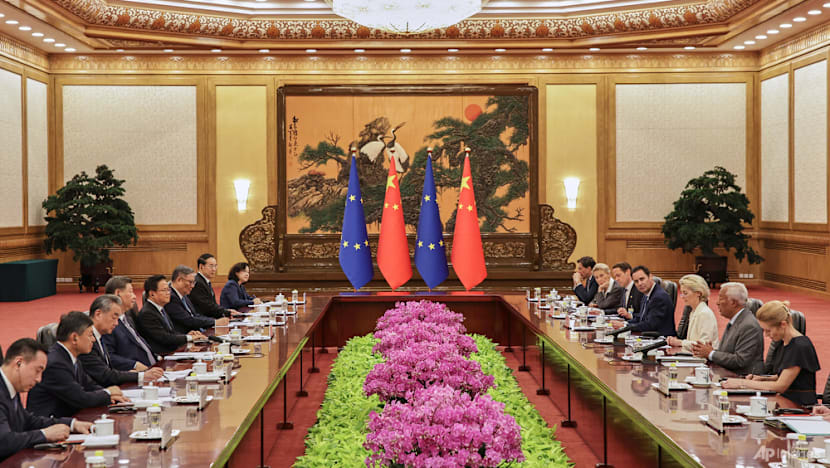

At the China-EU summit in July, European Council President Antonio Costa and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen met Xi and Premier Li Qiang in Beijing.

EU leaders warned that ties were at an “inflection point” over trade imbalances and China’s links with Russia, while deliverables were limited beyond climate language.

Just weeks earlier in Brussels, the China-EU High-level Strategic Dialogue produced no breakthroughs, instead reaffirming existing positions and setting parameters for managing disagreements ahead of the summit.

Both sides stressed the need to “manage differences”, maintain communication channels and avoid escalation, highlighting how far apart member states remain on China and how much EU-level engagement has shifted from advancing cooperation to containing friction.

EU unity has also been tested in sharper ways - including the ability to issue common statements at all.

In Jun 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement at the UN Human Rights Council criticising China’s human rights record, a move EU diplomats said undercut efforts to confront Beijing.

In 2021, Hungary blocked an EU statement criticising China over Hong Kong’s national security law, Reuters reported.

On the economic front, fractures have been visible even when the EU ultimately moves ahead.

In the vote that cleared the way for definitive EU duties on China-made electric vehicles, member states were split - with a large bloc abstaining and several voting against, underlining competing national interests in trade with China and differing exposure to potential retaliation.

Some governments have also leaned into closer engagement with Beijing, complicating Brussels’ efforts to keep a common front.

Hungary, which has courted Chinese investment in batteries and EVs, rolled out a notably warm welcome for Xi during his state visit to Budapest in May 2024 and upgraded bilateral ties, even as EU leaders elsewhere stressed “de-risking” and the need to protect European industry.

That backdrop helps explain why Starmer’s visit is being watched not only for what Britain signals, but for what it indicates to European capitals and Brussels about how far bilateral engagement with China can go without complicating wider European coordination, analysts said.

Possible outcomes from the trip, analysts said, are likely to be concentrated in areas that are politically easiest to sell at home.

“The most consequential outcomes will be those that institutionalise problem-solving channels and survive domestic political shifts,” said Li, pointing to “low-friction wins” such as revived trade and business dialogues and cooperation in non-sensitive areas like climate and health.

Herrero said the UK’s comparative advantage is also likely to shape the deliverables, with Britain pushing services exports such as education and finance, while Chinese firms look for green technology investment openings in the UK.

From a Chinese policy angle, Sun said the broader direction points to a “stable but not close” new normal, where disputes are contained and transactions continue, rather than a return to high-trust alignment.

INDIVIDUAL OVER COLLECTIVE ENGAGEMENT?

For Beijing, dealing with European capitals individually offers flexibility and leverage that are harder to secure through Brussels, said analysts.

Bilateral engagement allows China to tailor incentives, pace cooperation and send calibrated political signals, while sidestepping the EU’s consensus-driven constraints, they observed.

Herrero said bilateral deals make it easier for Beijing to “divide Europe”, encouraging competition among capitals and lowering the political and economic price of cooperation.

Working country by country, she said, also reduces EU-wide scrutiny, allowing China to secure more favourable terms than it might through bloc-level negotiations.

The appeal of the capital-by-capital track lies in how precisely it can be deployed, said Li from RSIS.

The EU, he noted, is procedurally slow and bound by consensus, while national governments offer room for bespoke economic packages and targeted political signalling.

China’s leverage is most concrete where individual member states can influence EU coalition dynamics, including votes on trade-defence measures or how technology and infrastructure restrictions are implemented, added Li.

The alternative is engagement with the EU as a bloc, through formal summits and institutionalised dialogues, noted observers.

China continues to engage the EU as a bloc where decision-making authority rests in Brussels, particularly on trade policy, regulation and sanctions, analysts said.

Last July’s China-EU summit in Beijing and the China-EU High-level Strategic Dialogue earlier in Brussels underscored that Brussels remains the primary interlocutor when binding rules, tariffs or sanctions are at stake, Li noted.

But analysts said those formats are often narrower, more contentious and slower-moving, reinforcing Beijing’s incentive to complement them with bilateral outreach.

Europe also stands out when compared with how China engages other regions.

In Africa, Central Asia and Latin America, Beijing more often uses region-wide or bloc-style frameworks as its primary diplomatic frame, such as the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, the China-Central Asia summit mechanism and the China-CELAC Forum.

While projects under these platforms are still largely implemented bilaterally, agenda-setting and optics are multilateral.

In Europe, by contrast, China actively toggles between Brussels and national capitals, and has experimented with sub-groupings such as the former 16+1 framework with Central and Eastern European states, analysts said.

The 16+1, later 17+1, was a China-led cooperation framework launched in 2012 to engage Central and Eastern European countries. It expanded in 2019 to include Greece, before several members later withdrew.

From Beijing’s policy perspective, the goal is not simply tactical advantage but longer-term manageability, said Sun from CISS.

“The ideal outcome is … for Europe to remain a key anchor capable of sustaining dialogue and transactions in a competitive environment.”