Fake it till you make it? Inside China’s ‘pretend to work’ trend as youth face surging unemployment

It may sound playful, but experts say China’s “pretend to work” trend masks a sobering reality: a generation taught to strive now struggles to find its place.

At Pretend To Work Unlimited Company in Hangzhou, applicants who pass an informal screening are welcomed with a mock interview “success” sign. (Photo: CNA/Bong Xin Ying)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SHANGHAI/HANGZHOU: Every weekday morning, Xiao Ding, 30, begins her day like most other young working professionals in Beijing.

She gets dressed, gathers her things and then heads out to a public library, where she sets up her laptop and spends the day “working”.

Except she’s unemployed.

“I haven’t told my family that I quit my job,” she said. “Until I find where my future lies, I don’t want to pass on my anxiety to them.”

The routine, according to her, is not about deception but discipline. After nearly eight years in tech marketing, she quit her job in 2023 and has now been unemployed for 22 months.

“I choose to pretend to work for two reasons: One, to keep a regular daily schedule. Two, to give myself the pressure of ‘going to work’,” Xiao shared with CNA.

But the search has been punishing. Even after sending out more than a thousand resumes, she has only landed four interviews - all of which were unsuccessful.

“I chalk it up to the (current) hiring climate being poor,” Xiao said.

During the lowest point of her job search, she spent entire days in bed doomscrolling on her phone.

“My whole body hurt from it,” she said. “That was when I really understood what ‘living in a daze’ meant. I felt I had no value to society at all.”

And she isn’t alone.

In China, fresh graduates and young adults unable to find jobs are coping by playing pretend - heading to libraries and cafes to maintain a semblance of a working environment amid harsh realities.

China’s youth unemployment rate rose to its highest level in 11 months in July. The urban jobless rate for the 16-24 age group, excluding students, rose to 17.8 per cent, as a record number of graduates entered the job market.

Playful on the surface, the “pretend to work” trend masks a sobering reality. For a generation taught to strive but now struggling to find its place, experts say it is a coping mechanism laced with irony and humour.

“Much like the idiom of 'lying flat', the act of pretending to work carries a tone of self-mockery and playful resignation,” said Zhan Yang, an associate professor of cultural anthropology at Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU).

“It reflects not only disillusionment but also a creative, even ironic, engagement with societal expectations.”

It is especially tough in China where one’s self-worth “remains deeply entangled with a culture that values work and productivity”, added Zhan.

“Pretending to work” is a way for youth to “maintain routines, identities, and social belonging in the absence of meaningful labour”.

“PRETEND TO WORK” COMPANY

Some take “pretend to work” further, renting desks in mock offices that recreate the rhythms of work - minus the employer.

Equipped with computers, desks, meeting rooms and internet access, these spaces are gaining popularity in major Chinese cities like Shanghai, Shenzhen and Chengdu.

In a sunlit office located on the outskirts of Hangzhou, a dozen young people sit quietly at their desks.

Some type intensely, others scroll through dashboards on monitors. A few murmur into headsets as they pick up calls.

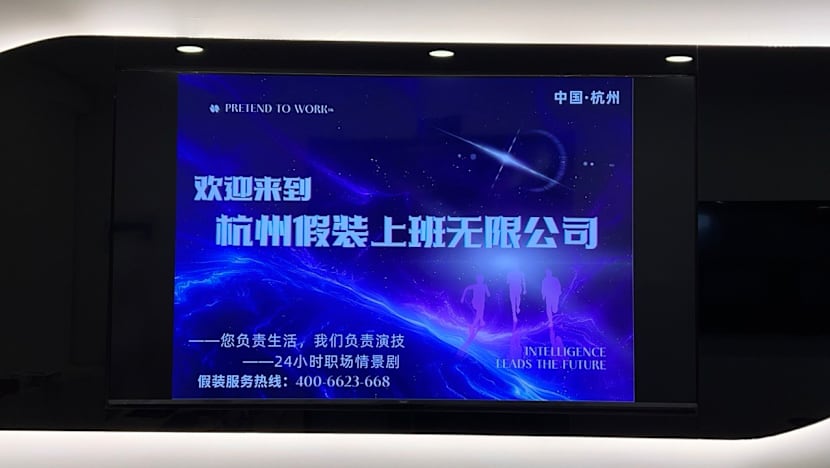

A printer hums in the corner. At the entrance, a wall-mounted sign in a playful font reads: “You handle life, we handle the acting - a 24-hour office roleplay.”

This is the premise of "Pretend to Work Unlimited Company", a mock office that has gone viral on Chinese social media.

With fees as low as 30 yuan (about US$4) a day, it offers “employees” a way to simulate the office experience: rent a desk, clock in at 9am, maybe even wear a “company badge”.

The operation is run by Chen Yingjian, a local entrepreneur who hopes to provide a functional safe space for young people as they navigate their job search.

The idea was conceptualised in July, almost by accident - when a friend’s unemployed son had asked if he could simulate a job interview in his office.

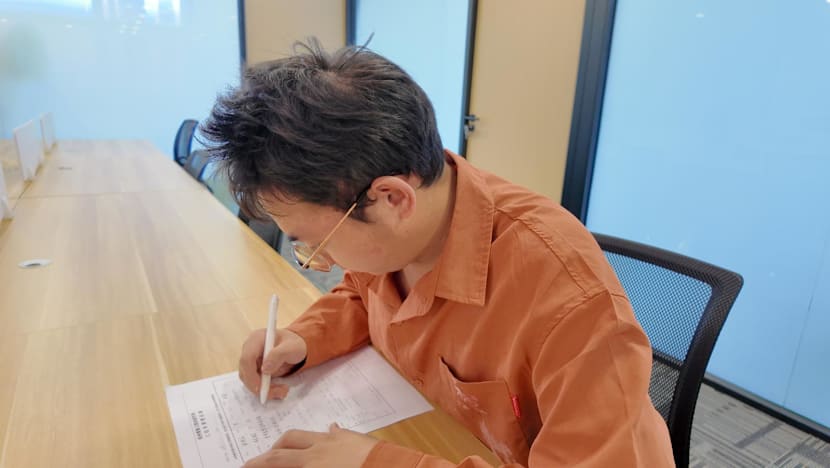

In less than a month, Chen has received thousands of inquiries. He screens applicants personally - welcoming those with concrete plans and rejecting others he believes are not serious about being there.

In this space, there are a few rules: no sleeping, no gaming and no noise.

The vibe is focused.

In addition to job searching, many are also there to work on startup ideas, prepare for exams and call clients. Some often stay on well into the night.

“We provide emotional value - helping (youngsters) regain confidence (and) not feel lost,” Chen said.

“Pretending means imitation,” he added. “And imitation means effort. If someone is willing to pretend, it shows they want to do something, that they’re motivated.”

“Those who really want to ‘lie flat’ won’t come here. Why would they? A bed at home is more comfortable.”

Settings like this can be helpful, said PolyU’s Zhan, noting that it is important for young jobseekers not to feel alone in the current tough climate.

“The recognition that one is “not alone” in facing unemployment or delayed adulthood becomes critical for sustaining a viable sense of self,” she said.

One regular is 19-year-old Yuan, who arrives at the space at 9am almost every day to work on his budding pet business, selling kittens and puppies on social media apps like Douyin.

“My routine here is definitely better than at home,” he told CNA. “At home I would get lazy.”

“It’s like studying,” he adds. “If everyone around you is studying and you’re on your phone, you would feel out of place.”

“Here you’ll see others working and will also feel like finding something to do. It’s to be influenced by immersion,” Yuan said.

Yue, a 21-year-old final-year business student from Yunnan, has spent his summer working part-time at the Pretend to Work office.

The experience opened his eyes to what his peers have been going through, he said, and is preparing him for what he too could soon face after graduation.

Yue sees the mock office not just as a place to be productive, but as a buffer from pressure and misunderstanding at home.

“(For instance), if I stayed home all day just shooting or editing videos, my family might not see that as real work. They would rather I go out, have a fixed workplace, or become a state-owned enterprise employee,” he said.

“It makes them feel secure. That’s the older generation’s thinking.”

“But today, things develop so fast that not many people can land those kinds of jobs,” he added.

For many young adults, a job is more than just a source of income, said Zhou Yun, an assistant Sociology professor from the University of Michigan. A meaningful job shapes one’s identity, affirms social belonging and offers a clear path towards adulthood.

“Employment is one of the key milestones in the transition to adulthood,” she said. “Beyond money, it holds a multitude of meanings - the promise of independence, a sense of fulfilment, a clear place in the social structure, or aspirations about a better future.”

“This system of meanings also reflects broader, societal level norms about adulthood - what counts as ‘productive,’ what kind of life is regarded as ‘ideal’, what goals and pursuits are seen as ‘worthy’.”

But not everyone in the office is in their 20s. Some are in their 30s and 40s - in need of a stable and affordable office setting.

After two years of working from home, Li Jianye, a 35-year-old Hangzhou-based entrepreneur, said she reached a point where her home environment was no longer conducive.

She began to look at spaces like self-study rooms. “But those are mainly for students and you are expected to keep very quiet,” she said.

“I might have to hold meetings with clients, so I need a meeting room. I (also) might need to get on calls with clients, so I need that kind of setup. Sometimes I also need to print documents. Basically, I need a fully equipped office-type workspace to support my work.”

She had seen videos about the company and ads on short-video platforms. While the marketing was playful, the working atmosphere was focused and serious, she said.

And it helped her stay accountable. “Here, I have a rational plan for what I do each time, which makes work very efficient. When I see others striving around me, slacking off (just) wouldn’t feel right,” she said.

Sun Lei, 42, is another mid-career consultant who joined the space recently. Like Li, she also needed a quiet place to “really get work done”.

“At home, it’s impossible to concentrate,” she told CNA. “Having kids, with parents around too, my focus is always broken. I really want an environment like this, where I can settle down and work,” she added.

She had previously rented a small one-room office but found it isolating and too relaxed.

“I ended up tending flowers, drinking tea and watching dramas,” she said. “My efficiency dropped.”

Productivity is also infectious, she said, recalling once sitting next to a very focused co-space worker.

“(There was) someone next to me working very seriously (and) made me feel embarrassed about watching dramas, so I didn’t,” she said.

The sharing of ideas was another nice surprise, Sun said. She has learnt about business models like AI products and cross-border e-commerce. “That was valuable,” she said. “That broke some of my old perceptions.”

BEYOND “LYING FLAT”

On the surface, “pretend to work” sounds like a meme, or perhaps a symptom of a generation disengaging from hustle culture.

But the phenomenon of pretending to work is different from “lying flat” - a concept that has taken off among young generations of Chinese adults in recent years, who are choosing less stress and pressures over career success and material wealth.

“Both are strategies through which young people seek to construct a meaningful life in the absence of stable employment,” said Zhan.

“These tactics represent different ways of navigating uncertainty, forming new identities, and adapting to shifting social and economic realities.”

Xu Jing, an anthropologist at the University of Washington, said that the young people in China “are still quite striving”.

“Their views on work are shaped by the educational culture. From a very young age, they were told to work hard.”

For decades, PolyU’s Zhan notes, young people in China have been urged to work hard and compete, with the promise of prosperity and social recognition.

But with fewer guarantees of that future, some now cling to its structure as a form of psychological continuity.

“In the Chinese context, ‘pretend work’ may be read as a way of waiting for inclusion, for a real job, or for a dignified future,” Zhan said.

“This phenomenon reflects the helplessness of youth when they become unemployed,” said Cai Shenshen, a lecturer in Chinese Studies at Monash University, citing the broader impact of economic woes, an oversupply of university graduates, and limited social welfare protections.

Observers note a lesser-discussed aspect of the trend: these office spaces offer low-cost infrastructure for China’s rising class of freelancers, sole proprietors, and remote professionals.

Xu says such spaces suit emerging professional identities like livestreamers and freelancers.

Such venues provide “a very pragmatic solution for people who are trying these new kinds of professional pathways,” said Xu.

“People are not just wasting time,” Xu said. “They are actually quite self-disciplined … they can feel better about having some agency in their own lives.”

Pretending to work has helped Xiao Ding maintain a sense of normalcy.

“It makes me believe that once I do get a job, I’ll quickly adapt to the pace and won’t be fired during probation,” she said. “That belief gives me more confidence in the future.”

When asked about the "pretend to work" trend growing in popularity, she said: “I don’t think it says something about the character of our generation. It only shows that this era offers fewer job opportunities.”

“Facing a bad economy, young people make all kinds of choices,” she added.

“Some shed the scholar’s robe and become waiters, delivery riders, ride-hailing drivers - some keep studying. Some try to make a living as influencers (while others) cut expenses and accept low-desire lifestyles.”

“And of course, many still keep grinding to find jobs.”