IN FOCUS: 35 years of people and purpose - this is Singapore's MRT story

It started with just five stations in 1987, and today has grown to six lines and counting. CNA speaks to pioneers at the heart of Singapore's MRT network on its 35th anniversary.

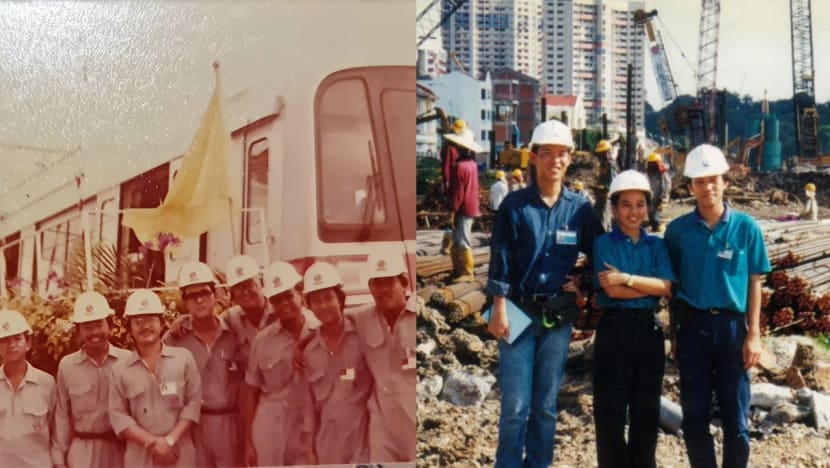

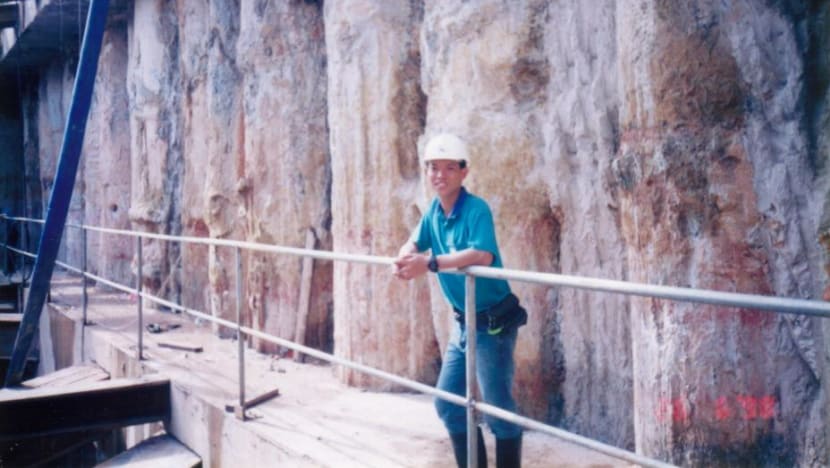

SMRT's Michael Yeo (first photo; third from right) during the first train arrival ceremony in 1986, and SBS Transit's Quek Chin Hock (second photo; first from left) as an intern with LTA in 1998. (Photo: Michael Yeo, Quek Chin Hock)

SINGAPORE: In a career spanning more than two decades, civil engineering graduate Quek Chin Hock particularly remembers the day he had to speak to a monk about the structural integrity of his temple.

The 50-year-old was then a student intern assisting Land Transport Authority (LTA) engineers to oversee construction work at Farrer Park station on the North-East Line of Singapore's mass rapid transit (MRT) network. He was tasked to visit the station’s surrounding residents and assure them that their homes would be fine.

One such home was an old temple, and its resident, a monk.

“I had to go in and meet with the old monk to explain that I needed to install technical instruments on his old temple and it’s for the good of his temple to let us monitor the structural integrity of the temple,” he told CNA.

“After talking, he finally understood our kind intent and he allowed us to install our instruments on his temple."

While Mr Quek was also involved in building the station, the engineer-by-training found that such “meaningful” interactions during his internship ended up shaping his career.

He joined SBS Transit after graduation and today heads customer experience and operations for the Downtown Line, where he frequently engages with people to understand their needs.

Mr Quek still finds the rail industry meaningful because it impacts so many people.

“It’s not like a small factory or a small company where your work only impacts a small group of people … compared to the rail industry. You will find that your entire life will be very meaningful because every day what you do, you are literally affecting thousands of people that need to travel on your train system,” he said.

And Mr Quek is not alone. Rail veterans took CNA on a walk down memory lane for the 35th anniversary of Singapore’s MRT network to reveal an industry driven by people and purpose from its inception.

LEAVING CAREERS, SWITCHING INDUSTRIES

Amid Singapore’s rapid social and economic growth in the early 1960s, the Government turned to the United Nations to devise a long-term framework for the country’s urban development. The study predicted that there would be a need for a rail system by 1992.

On Nov 7, 1987, the first five stations – Yio Chu Kang, Ang Mo Kio, Bishan, Braddell and Toa Payoh – opened on the North-South Line to strong public support.

By July 1990, two years ahead of schedule, more than 40 MRT stations, including sectors of the East-West Line, were operational.

With Singapore’s rail industry in its infancy, those who joined were not put off by the unfamiliar. In fact, many were even more keen to explore new ground.

As a student in Glasgow, Scotland, during the late 1970s, Mr Sim Wee Meng would take the train to visit his friends in London. The senior advisor (rail) at LTA remembers being “fascinated” that the London Underground metro system was able to “take in so many people, and doesn’t have traffic lights”.

One day, Mr Sim declared to his friend that if Singapore were to build something similar, he would quit his job and join the industry. When he responded to an advertisement in 1983 for rail engineers, he landed the job. This meant having to leave a flourishing career in consulting and take a pay cut.

“They said if I was a consultant that I’d also have the chance to work on the MRT. But I said, no, I want to be in the thick of action. They even flew in the big boss from New Zealand to convince me (to stay). I told him I already made up my mind, that it’s something I’ve been dreaming of and I really want to quit,” the 68-year-old said.

Mr Sim’s gamble paid off. His overseas experience as a consultant even helped him adapt to the different cultures of expatriates, from Hong Kong to the US, which Singapore had brought in to train the local engineers.

“Our bosses (who weren’t from Singapore) always reminded us that we were going to be the future, we were the pioneers, and if we don’t pick up things and learn, that is a missed opportunity," he added.

A similar love for the unknown compelled Mr Michael Yeo to leave his eight-year architecture career in the building sector.

Whether it was becoming a railway master in 1986, training others, taking on the role of chief controller, managing the entire operations control centre, working with engineers and contractors, or dabbling in smaller projects, Mr Yeo has since constantly seized the opportunities that came his way. But he considers projects his favourite job scope.

“Every time I go into a new project, I get the opportunity to learn. And every time when I do that, and the next project comes along, I add on. To me, it's really exciting. I get to improve myself. There is never a dull moment for me in SMRT,” the 65-year-old said.

“I just love learning new things, new technology coming in. I'm quite fascinated by how things progress.”

Mr Yeo’s urge to volunteer for new roles all the time eventually led him to be part of the driverless Circle Line that opened in 2009. Working on a new system meant he needed to change his mindset, which made him “very excited”.

And when the Thomson-East Coast Line came along, he took up the challenge again, becoming the head of the Thomson-East Coast Line project team at SMRT.

UNKNOWN TERRITORY, UNFAZED PIONEERS

Pioneer railway signallers with SMRT told CNA that they had no clue what signalling entailed when they went for their job interviews, but it didn’t faze them.

When she was still a polytechnic student, Ms Didi Tan’s interest in the rail industry was piqued by course mates who did an internship with the Mass Rapid Transit Corporation (MRTC) which was established in 1983. It was later renamed SMRT Corporation.

Even before graduating, she went for a job interview at the company, and became “very excited” when her interviewer explained the role of signalling to her. She was offered the job on the spot and began right after graduation.

“The interviewer told me signalling will be the system that controls the movement of a train from one station to another in a very safe manner. Your job will involve all the humans associated with it; the controlling side, the equipment side,” recalled the 58-year-old manager of SMRT’s resignalling project.

For the average commuter, think of railway signalling as the system that keeps you from being late. It ensures trains arrive on schedule, while keeping them a safe distance apart from each other, making sure they have enough braking distance to stop. It also routes trains down the correct tracks and platforms.

Ms Tan's colleague, engineering maintenance manager Ameer Abdul Rahim, likened signallers to "the heart in a body". The 59-year-old, who has also been in signalling for more than three decades, said that whenever any railway incident happens anywhere in the world, the first thing they check is "if your signal is correct".

Ms Tan and Mr Ameer have since realised signalling is “a very specialised field”. Even though people usually find the job “stressful” as they need to be detail-oriented and “100 per cent or even 105 per cent alert” all the time, they relish the challenge.

“For our project, such as where we make changes to the old system at night, we have to be very careful and watch what is being carried out. If we take out a wrong wire, it might cause the circuit not to work, then the train cannot run the next day,” said Ms Tan.

“You always have to watch what the contractor or workers are doing, then read the circuit and see whether the design is correct. … Some contractors fear people like us; you can see they are more prepared and do their homework first because we tend to be able to pick up (on things that are not right).”

BUILDING THE NORTH-EAST LINE FROM SCRATCH

Many who spoke to CNA expressed similar pride about working on the North-East Line, the world’s first fully automated underground driverless heavy rail rapid transit line, which opened in 2003.

When 63-year-old Chua Chong Kheng headed the North-East Line project around 1996, he found it “quite challenging” to devise a plan for an automated heavy metro line meant to carry thousands of people. Only “smaller” automated systems existed then, such as in airport rail links.

“First, we started developing what we call the operational master plan; how we expect the rail to operate. From there, it became the engineering master plan; what are the engineering requirements. Then we broke it down into the individual systems; what should be the design requirements you put into the specifications for the calling of tender,” said the deputy chief executive (infrastructure and development) at LTA.

“At the time, you always wonder whether things will actually pan out as what you plan, what you design.”

One challenge, for instance, was figuring out “how to take care of passengers” without a driver. The North-East Line thus became the first time cameras were implemented in the MRT.

“We needed a very strong operations control centre, which must have the capability to supervise, monitor and control the operations. That was the challenge … but in the end, it formed the basis for all our automated systems since then,” added Mr Chua.

Once the line was close to completion, the right people had to be hired to run it.

After an eight-year career in the electrical power industry, Mr Foo Jang Kae was offered the opportunity to set up the power and OCS (overhead catenary system) department of the North-East Line with SBS Transit in 2001.

The 55-year-old engineer, who has since headed the engineering division of the North-East Line, Downtown Line and Sengkang-Punggol LRT, found the prospect of being a “pioneer” in a “startup” very attractive.

“It’s like being given a Lego set. You have the chance to put the pieces together. It’s very much like you're given a blank sheet of drawing paper. That was the enticement, the attraction to it,” he recalled with a smile.

Now the head of engineering and performance for the rail division at SBS Transit, Mr Foo recounted one of the initial main challenges: Finding the right resources and people. These staff needed to be trained since they hailed from various disciplines outside the rail industry.

Moreover, the training for staff working in the operations control centre would take longer, since these folks were “very critical”, he added. “We had to select them very carefully; they go through psychometric tests to ensure they’re able to work under pressure.”

One such employee was Mr Anthony Mok, who started his rail career as the chief controller in the North-East Line’s operations control centre more than 20 years ago after leaving the computer manufacturing industry.

Like Mr Foo, Mr Mok too had to “handle these unknowns”, such as by documenting knowledge gained and passing it down to other controllers in the operations control centre.

“As a trainer, during that time, besides receiving some local training knowledge and skill sets from the supplier, I also had the opportunity to go to other rail systems in the world, like Hong Kong’s MTRC, to gain the knowledge and also ground experience from them,” said the 57-year-old who heads the North-East Line and Sengkang-Punggol LRT at SBS Transit today.

“And from the knowledge gained, we developed our own training plan, so that our staff can reach the competency level required to operate the trains as well as the station operations.”

Operating a line also meant learning how to deal with inevitable disruptions.

Senior advisor (rail systems and assets) at LTA Wong Wai Keong said his team was “triggered” to "change their mindset" when the overhead power supply system in the tunnel at Outram Park station snapped. He was with SBS Transit, the operator of the North-East Line, when the line opened.

“It was a very stressful moment because you know that when the system goes down, there are thousands of people out there waiting. The objective is to bring it back as soon as you can,” the 65-year-old said about the 2012 incident.

“From the operator’s perspective, the focus is not to find out immediately what caused it. We had to change the mindset of our engineers. The most important thing is we know what happened; how can we bring it back as close to normalcy as soon as possible?”

Following the incident, all the engineering teams at SBS Transit sat down and identified all possible failures in each system, helping them to recover partially or fully "in a much shorter time" for subsequent incidents, added Mr Wong.

NOT JUST ABOUT ENGINEERING

Today, the MRT network comprises six lines: North-South Line, East-West Line, North-East Line, Circle Line, Downtown Line and Thomson-East Coast Line. Construction for the Jurong Region Line and Cross Island Line are ongoing.

But as Singapore’s rail network grew, managing it soon presented more than just engineering challenges.

The main challenge was how to structure the rail industry in a way that achieves both cost efficiency and high quality, because it is “very hard to have both at the same time to a high degree”, noted Associate Professor Walter Theseira from the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

When operators started cutting costs to make profit, the Government took on “some risk for system finances and started to provide more financial support to operators for training, manpower, and maintenance”. But finding the right balance is a challenge, he said.

On the ground, “stakeholder management” is a constant challenge. This includes trying to explain engineering “jargon” to the public.

Highlighting the complexity of civil engineering, LTA’s Mr Chua explained that dealing with “very complicated” ground conditions, and working very close to properties, developments, and roads means “you just can’t relax”.

“Underground construction is very complex. It’s made worse, because underground, you have very variable geological conditions. It can be very fine sand to very soft clay … to very hard rock. And sometimes we get all this in one tunnel,” he said.

Working underneath the roads means two things, added Mr Chua.

“First, you have to get the services out of the way. That’s why our projects become expensive. Just the amount of services we need to move aside – the Singtel cables, the power grid cables, everybody’s cables I need to move aside, and all of them have their customers and stakeholders to take care of. It takes a lot of time and costs to do that,” he explained.

“Second, I don’t want to disrupt the roads on top. As I build, I want my roads to continue functioning. So what I do is I move the road, so I can build here, and when I finish this, I move it back. We do it in stages; what we call road diversions. If you have the space to move the road, it’s fine; if you don’t have the space, what we do is lane by lane.”

During construction, complaints about noise from residents living in the area are expected. But it’s about compromise; if residents want a station’s entrance right outside their house, construction must take place near their homes too, Mr Chua said.

“Sometimes, (your job is) not just about engineering, but being in a position where you have to educate, you have to explain and help to manage some of these stakeholders,” he added.

“The key for engineers is that after you’re good on paper, you’re good at technical skills, the next thing is how can you communicate, how can you explain. That’s a skill which is not easy. Somehow engineers tend to go back to technical jargon which people don’t understand.”

LTA’s Mr Sim admitted that as he rose to become a group director, his work became “less and less technical” and “more and more (about) explaining to the Members of Parliament, to the residents, to our corporate communications department” about the work.

“Most of the time when you are sleeping, our people are working, whether it’s underground doing tunnelling work or making sure that launching the viaduct is very safe. ... A lot of them have their family routine being disrupted. But why do they like this? Because they’re very passionate people,” he said.

COMMUNICATIONS BROUGHT TO THE FOREFRONT

Public communication becomes even more important in the wake of a major incident. For Mr Chua, the Nicoll Highway collapse in April 2004 didn’t just emphasise the importance of safety, but also the need to understand and communicate what went wrong.

The accident happened when a tunnel being constructed for use by MRT trains collapsed, resulting in a deep cave-in that spread across six lanes of Nicoll Highway. It killed four people and injured three.

“That was a very telling time, because it’s the first time we had such a major accident … and it was quite painful … how the thing panned out in court. As a result of that accident, a lot of new processes were introduced. It made the whole construction design for civil works more complex. … It was a low point but it gave us an opportunity to recover. And we did,” he said.

The early to mid 2010s further reinforced the need for good communication from rail operators when public frustration about train breakdowns turned SMRT's checkered few years into a crisis communication case study.

Two major train breakdowns had happened in December 2011, resulting in a Committee of Inquiry being set up.

The first happened during the evening rush hour on Dec 15 – about 127,000 commuters were affected by a disruption lasting five hours. On Dec 17, another disruption began in the morning and lasted seven hours; it affected about 94,000 commuters.

Following the spate of train breakdowns, the then CEO of SMRT, Saw Phaik Hwa, resigned in January 2012.

The debate about whether SMRT or the Government was responsible for the rail system not performing "as expected" emerged around then and continued during the tenure of former SMRT CEO Desmond Kuek, who succeeded Saw Phaik Hwa in October 2012, noted Assoc Prof Theseira.

“From the Government's point of view, having privatised rail operators means that the rail operator has primary responsibility for maintaining the system and assuring reliability. But from the operators' point of view, the Government, as regulator, also bore responsibility for putting into place a fare structure that made it difficult for the operator to have the resources to get the job done," he said.

In fact, navigating public sentiment proved so significant during this period that SMRT’s former vice-president of corporate communications Patrick Nathan’s resignation in 2018 made headlines. But he believes that “media reporting was fair”.

“Obviously (the reporting) cannot (help) but be negative because it's a disruption. But we continued to engage the media to tell them what we're doing about it; the renewal, the upgrade programmes,” the 61-year-old said.

For instance, SMRT invited the media behind the scenes of key projects, such as observing what happens when a section of the track goes through resleepering works during “silent hours”.

Mr Nathan stressed that more time was spent communicating about such renewal and upgrade programmes that would “restore the reliability of the system”.

This was important because “crisis communications don’t solve crises”, but simply inform and explain the crisis to the public. In reality, putting effort and resources into operations, maintenance, and engineering prevents crises from occurring, he said.

“The sacrifices of our commuters, the people we serve, helped tremendously as it gave our people the much-needed time to implement these programmes which would lead to longer term improvements to the system,” he said.

In early 2018, Mr Nathan started to see improved reliability and performance, allowing commuters to finally “enjoy the dividends”.

IMPROVED SYSTEM, BUT “FAULT FREE” SYSTEM IMPOSSIBLE

Things are noticeably different today. Train reliability hit a new high of 2.48 million train-km between delays in the first quarter of 2022, compared to 1.7 million train-km in the same period last year.

The mean kilometre between failures is used as a measure of reliability by train operators around the world.

According to figures from LTA, there was just one breakdown that exceeded 30 minutes across the MRT and LRT network during the first quarter of 2022 – a train fault on the North-East Line on Jan 23.

But while reports of breakdowns nowadays are “very few and far between” and the engineering teams do their best to prevent failures, the occasional disruption is unavoidable, noted SBS Transit’s Mr Foo.

“Sometimes failures can be due to very simple things, like something being stuck on the tracks at the train doors. It can be a pen or hairpin; it prevents the door from closing. It can be as simple as that. When the door doesn’t close, the train cannot move,” he said.

“Unfortunately there are some reporters who like to talk about poor design and poor quality. I must defend this because you can put in your 100 per cent, but you will never, never be able to make a system fault free,” added LTA’s Mr Chua.

Nonetheless, once a disruption occurs, engineers race to recover service within the golden window – five minutes.

“Five minutes has always been the measure. Five minutes is not something you can actually feel; commuters won’t be late. Because our average train frequency is about 120- to 180-second intervals. So if you miss the train, you wait on the platform, it’s about five minutes,” Mr Foo explained.

“Anything beyond 15 minutes, that’s where people start to feel it. And half an hour is a no-no.”

Ultimately, this current phase of MRT development is about making public transport “superior to private transport", so people choose to take public transport "not because it's the only affordable option for them, but because it's better than buying a car or taking a taxi", noted Assoc Prof Theseira.

PRIORITISE CUSTOMER SERVICE, MENTORSHIP FOR YOUNG ENGINEERS

To that end, customer experience must be a priority for operators, during service disruption and when everything is running fine, noted Mr Mok, who also heads customer experience and operations for the North-East Line and Sengkang-Punggol LRT.

“For customer experience and operations in the MRT, we have two key components. First is smooth and timely travel of the train service,” he added.

“On top of that, we also need to enhance their stay inside the rail network. We need to take care of a different age group of commuters. For example, we change our running speed of the escalator to a slower speed for the elderly … and (make) our stations dementia Go-To points.”

A single train load can take up to 1,700 commuters, so if a train is not handled properly, one can expect 10 per cent of these commuters to have “a very bad experience” travelling on the MRT, resulting in a “very big repercussion”, added Mr Mok.

After serving commuters for 35 years, senior station manager at SMRT Tamilarasi Balasubrammany has just one tip: Put yourself into their shoes. Usually, it works.

“Whatever you do, customer service comes first. Passengers must feel like they’re at home. What’s the difference from other countries? Singapore transportation is very friendly, very safe,” the 55-year-old said.

“As station staff, we’re trying our best, despite whatever personal problems we have on our mind. I always tell myself, whatever it is, when you put on your uniform, put those things aside. Perform.”

Like safety, customer service is of "paramount importance to a transport company", added Ms Tamilarasi.

“I love to help customers. After a few years doing that, I came to know that when you help passengers, they recognise my efforts. Sometimes they even come down with flowers and handmade things. Even kids’ parents come down, telling me their kids were unable to travel without a ticket and thanking me for helping them. They come and give us a card."

Within the industry itself, mentorship for younger rail engineers plays a huge role in improving the MRT network. Some told CNA they take great joy in learning and passing on knowledge to younger colleagues.

“Not just the projects side (which I enjoy), but also the operations. You get to evaluate the system, change the design to make sure it’s safe, then teach it to people. To me, that is very satisfying; personally, it is a better compensation,” said SMRT’s Mr Yeo.

Building trust with others in the industry is equally crucial, as being able to trust the people you work with keeps the entire system safe, he added.

When she gets to work with younger staff, SMRT signaller Ms Tan treats them the way she was treated by her own seniors when she first joined the industry: By sharing her stories.

“I’ve travelled overseas for work, so I share the interesting stories that happened overseas. I love to make (new engineers) realise that railway signalling is a very interesting job. If you can get that interest, it can bring you to a lot of places and let you learn a lot of things. ... Sharing is very important in this industry," she said.

In a recent speech by LTA’s Mr Chua at the graduation ceremony for engineers from the Singapore Institute of Technology, he shared that building MRT lines are not solely for the current generation but for many to come.

“You’re leaving behind a legacy. It’s more than just measured in terms of personal success. It’s about your contribution to the well-being of the country, contribution to the environment, to the population as a whole for the long term," he said.

"I think not many jobs can give you that kind of opportunity."