IN FOCUS: Danger zones - how workplace safety lapses are costing lives

While the COVID-19 pandemic has hit some industries in Singapore hard, there are systemic issues behind the recent spate of workplace accidents. Workers and safety consultants share their experiences on the ground working in higher-risk industries such as construction.

(Illustration: Rafa Estrada)

SINGAPORE: About a year ago, Bangladeshi worker Mohsin was climbing down scaffolding at a renovation site when he fell about 3m.

He was hospitalised for seven days with injuries to his back and hand as well as fractures in his leg. He could not walk for two months, said the worker, who only gave his first name.

It was raining that day and workers were hurrying to get off the scaffolding, he recalled.

“Suddenly rain coming … supervisor say: ‘Raining already, you (come) down, fast, fast, fast, fast’,” Mohsin said. “He is always pushing workers, you know, always he pushing.”

As he quickly climbed down, Mohsin slipped and fell. It took him about nine months to fully recover, then he went home for a break before returning to Singapore to work.

Such situations, where supervisors and workers act under time pressure, have been cited as one of the causes of workplace accidents, which have been on the rise in Singapore.

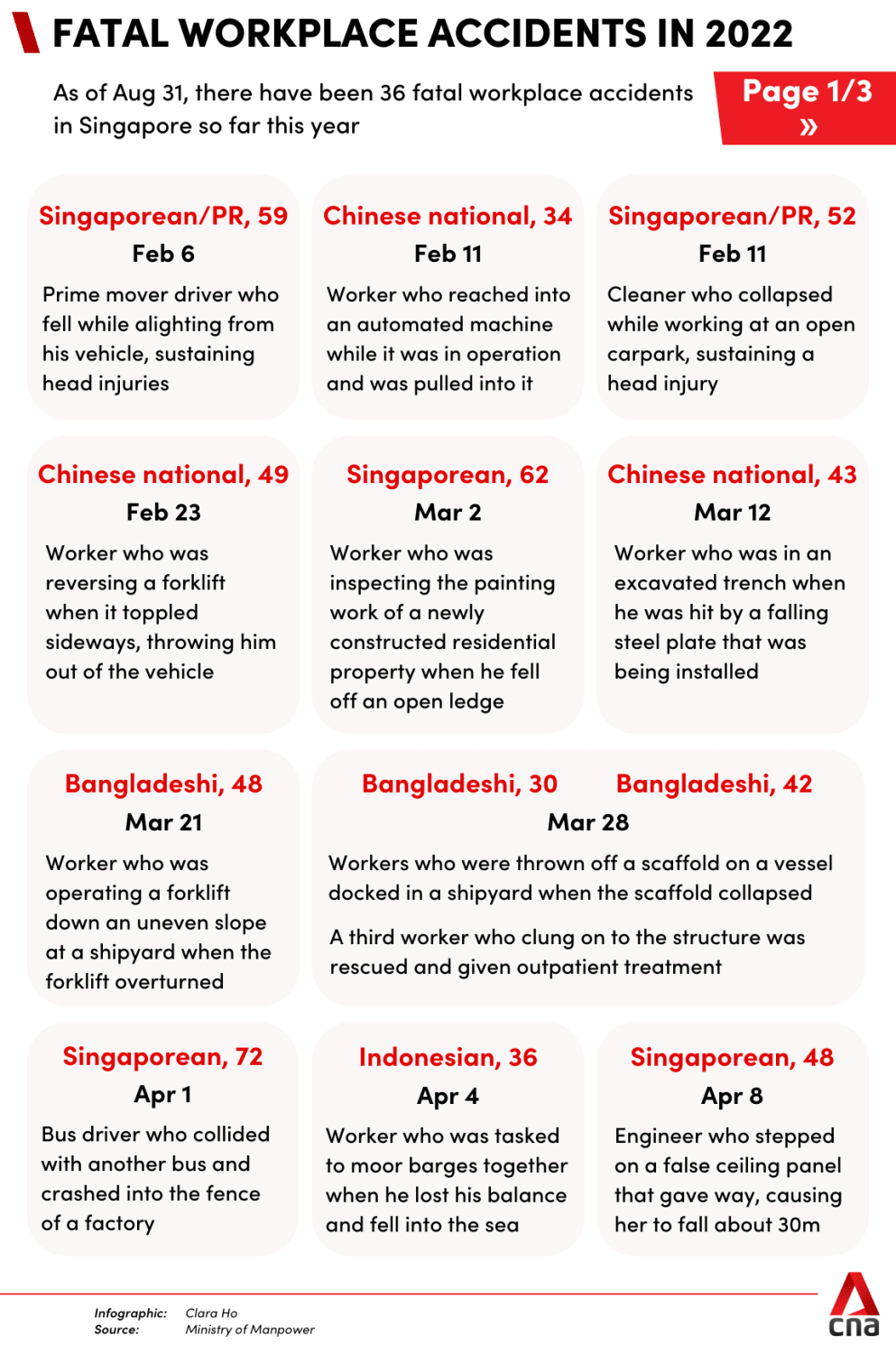

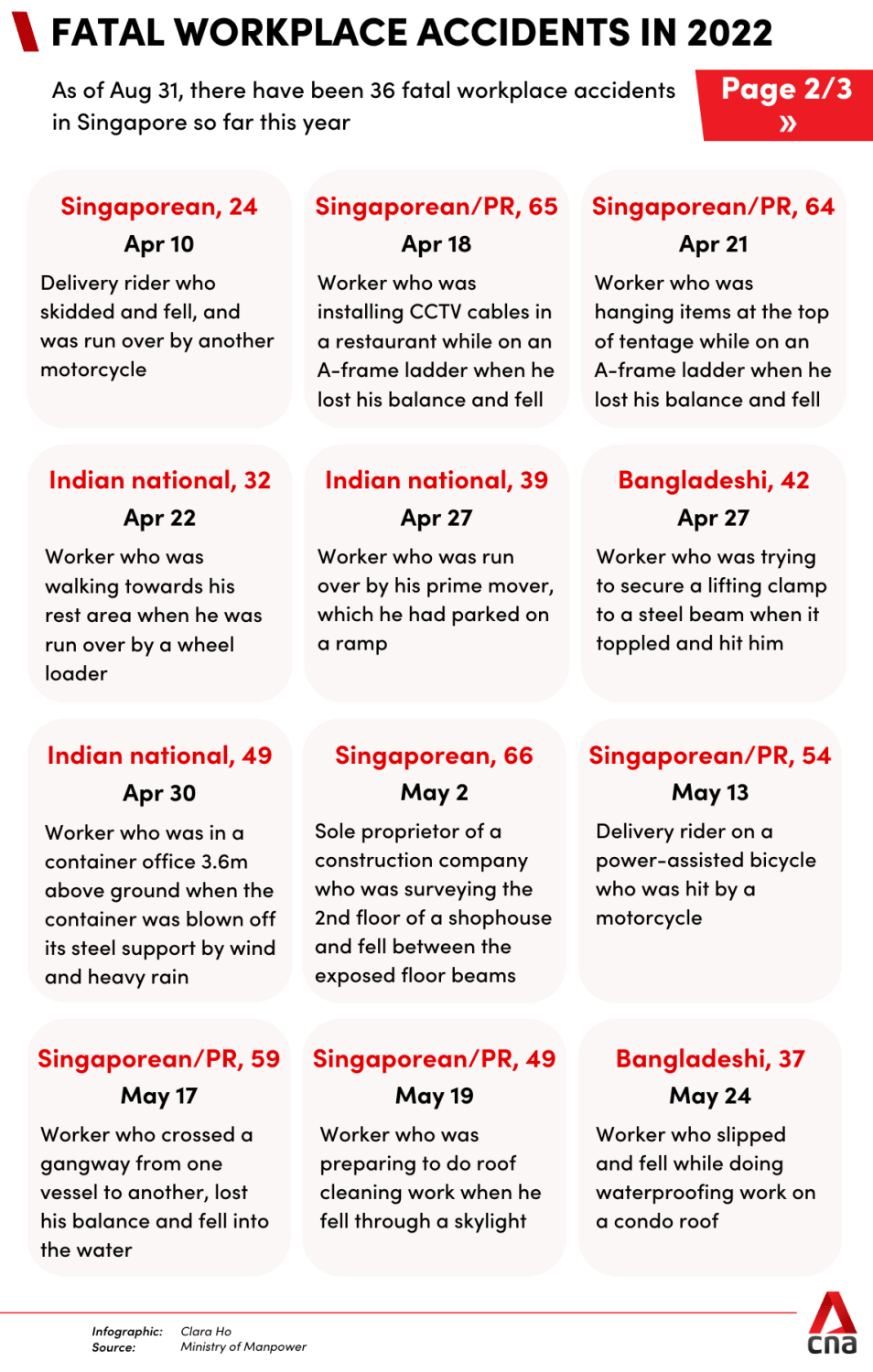

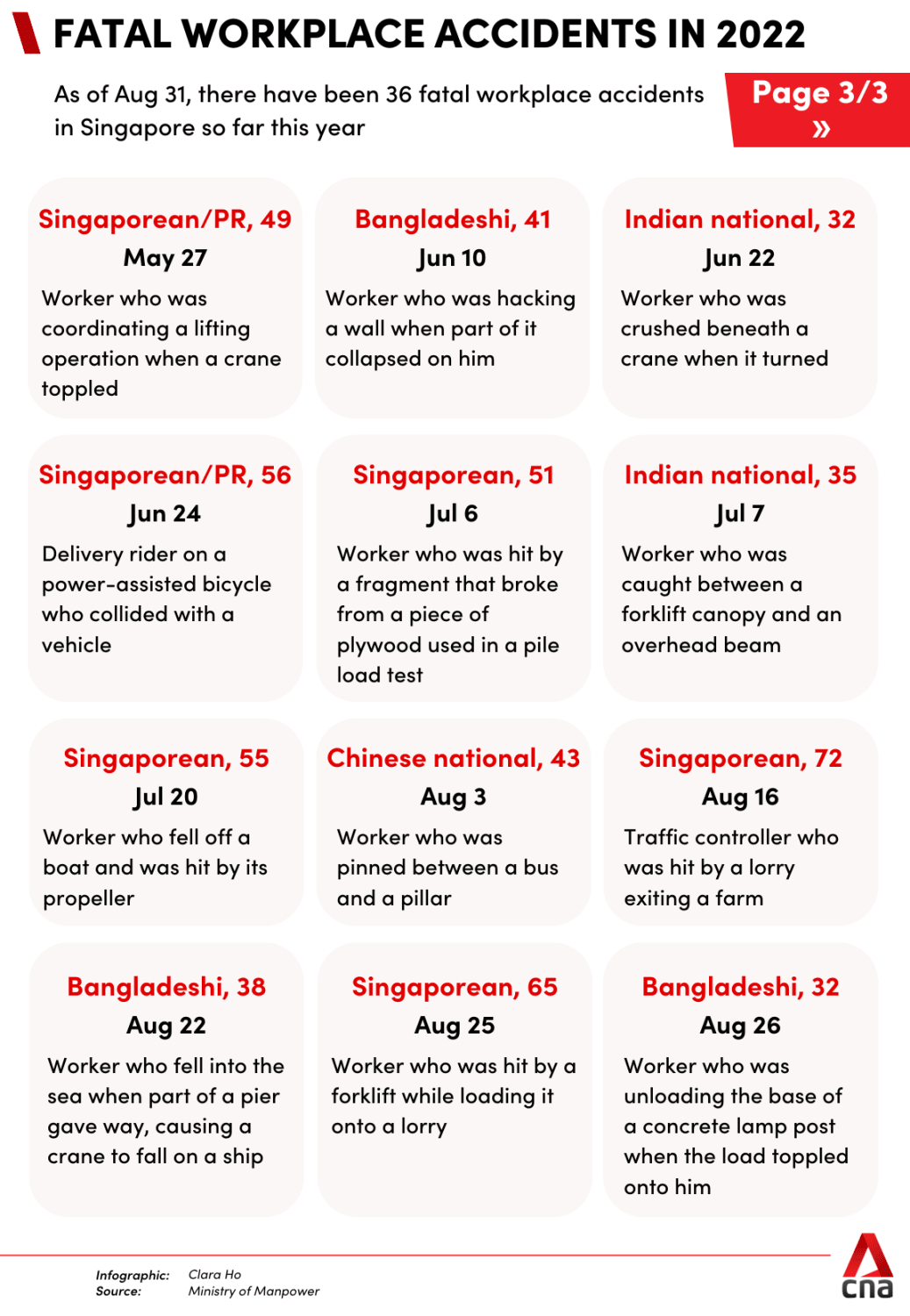

As of Aug 31, 36 workers have died on the job, compared with 37 deaths for the whole of 2021 and 39 in 2019. In 2020, there were 30 deaths, a lower figure as construction work was suspended during the “circuit breaker” period.

On Thursday (Sep 1), the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) pushed out a new slate of measures to boost workplace health and safety (WSH), and announced a state of “heightened safety” for the next six months.

From now until Feb 28, 2023, if the ministry uncovers serious safety lapses following severe or fatal workplace accidents, it will ban the companies involved from hiring new foreign workers for up to three months. All companies in higher-risk sectors are required to conduct a mandatory safety time-out to review safety procedures by Sep 15.

The demerit point system for the construction sector will also be revised so that the threshold for getting demerit points will be lowered. Once the penalty threshold is reached, the company can be barred from hiring foreign workers for up to two years.

These and other measures come on top of stepped-up inspections and higher fines that were introduced in April.

MOM warned especially about working at heights without proper safety protection, which was the most common workplace safety contravention found during its inspections.

Falling from heights is also the top cause of workplace deaths this year, like other years.

POST COVID-19 SPIKE

What’s different this year is that after the pandemic, as COVID-19 restrictions ease, projects have come back online, but many foreign workers, heavily employed in construction and manufacturing, have returned to their home countries - meaning that there’s more work but fewer workers.

Before the recent spate of deaths, the workplace fatality rate had fallen to 1.1 per 100,000 workers in 2021, from 2.1 per 100,000 in 2012.

Workplace accidents also spiked after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003, said safety consultant Goh Chye Guan, who had expected this post-pandemic spike in injuries and deaths at work.

“For two-and-a-half years, we stopped work, so there are a lot of things that can go wrong.”

For example, machines may not have been used or maintained, chemicals and materials could have expired and workers may be out of practice, he said.

But he also said that the accidents that occurred this year are “nothing unusual” in that the incidents result from the safety issues that have cropped up frequently in the past.

This points to systemic issues that have been exacerbated by cost pressure, tighter deadlines and the manpower crunch on the ground.

Executive director of the Migrant Workers’ Centre (MWC) Bernard Menon called these conditions a “perfect storm”.

“You have looming project deadlines, as a result, workers work overtime,” he said.

“Migrant workers are such that if you get the opportunity to work overtime and earn more money, most migrant workers would take that opportunity, willingly.

“But I think there's a downside to that. They work for too long hours, it's very, very easy to lose focus … in many instances, as we can see, (this has) led to tragic consequences.”

“WHEN CAN YOU FINISH?”

Mr Yong Jian Rong, chairman of the WSH subcommittee of the Singapore Contractors’ Association Limited, said that in Singapore, safety culture is not embraced consistently by all, and safety is often overtaken by other priorities.

“Often, the question you hear being asked to the contractor is ‘When can you finish?’, rather than ‘What are the steps that you have taken to ensure this is done safely?’" he said.

“The contractor is expected to work safely at all times but is not always rewarded when things are done in a safe manner.”

However, if the work is delayed, there is a high chance that penalties could be imposed on them, he said.

This can translate to managers pressuring supervisors, supervisors rushing workers, and workers themselves not taking safety seriously, so as to expedite the work.

Mr Colin Seah, safety consultant at QE Safety, who has been in the industry for more than 10 years, gave one example: He has asked workers to erect barriers at work sites to prevent falls, only to have them removed later, sometimes the very day they were put up.

When he asked them why, the answer could be that the barricade got in the way, as construction materials are being moved up to the higher floor through that access point.

Contractors and construction supervisors have told him that Singapore works on an “Asian schedule” - everything has to be fast, but wants Western standards of safety at the same time.

Expressing the frustration he feels at times as a safety specialist, he said: “There’s a problem - we solve it, but sometimes our hands are tied.”

There can be many underlying reasons for taking shortcuts, he said, ranging from time pressure, lack of manpower or experience, to inadequate resources - as safety gear can be expensive.

NEW, INEXPERIENCED WORKERS

Mr Yong pointed out that Singapore’s workforce in the construction sector is largely made up of foreign labour that constantly rotates every couple of years.

“This makes training very tedious due to the sheer amount of repetition that has to be done on a daily basis,” he said.

Experienced workers CNA spoke to said that new workmates tend not to be so aware of safety, even if they have been trained. Part of the reason is that they have so much to absorb and learn that they lack the bandwidth to also think about safety.

Mr Hasan Samim, an electrical and instrumental technician and site safety supervisor with Rotary Engineering, said he has seen more new and inexperienced workers coming to Singapore after borders reopened.

“There are a lot of new people, inexperienced people coming in for work currently … they don't have enough experience or knowledge to protect themselves or protect others,” he said.

“When you are new, you are also scared to do something - scared to take precautions, scared to talk also.”

Besides giving them daily briefings on safety, he groups experienced workers with inexperienced workers into teams so that the ones with experience can watch over the new workers, he said.

Mr Omar Sakib, a safety supervisor, said that workers on the job for long hours, especially in the sun, can also result in injury.

He recounted how, about two months ago, a worker fainted from heat stroke while paving the road with asphalt. The machine he was using to level the road then ran over his foot. Supervisors need to properly manage the workers’ shifts to manage their fatigue, he said.

FEAR OF SPEAKING UP

Mustafa, a worker who was injured a few months ago after falling about 2m, told CNA that his company, a small construction firm, was constantly short of manpower and pressuring the workers to meet deadlines.

The Bangladeshi worker, who did not want to use his real name, said that the day he fell, there were three of them at the site, and they climbed up to the roof of the house using a ladder they leaned against the wall.

He supported the ladder while his co-workers climbed up, but had no one to help him hold the ladder, which slipped as he was climbing it. Besides the fact that there were not enough workers on site, using an unsecured ladder to climb up to the rooftop was also unsafe.

Mustafa said that while he sees safety harnesses at the company’s office, they were not distributed to the workers, and not used.

He said: “Every time, (they) give less workers and rush to do fast … your safety - follow or not follow, it doesn't matter.”

He knew that these practices were unsafe but did not feel that he could speak up.

Mustafa returned to Bangladesh for a break just before the COVID-19 pandemic, then for two years, he couldn’t come back to Singapore to work as there were border restrictions.

Having run out of money, he wanted to come to Singapore as quickly as possible and took up any job that was available. He also paid more than S$4,000 in recruitment fees just to come here and work.

He said that if he had reported his employer, he would have been sent back home. “I have a lot of money I loan, so if I go back, the money how do I pay?” he asked. But now that he has injured his leg, he may not be able to do hard labour at all in the future.

Mr Luke Tan, case manager at the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME), said that employers hold a lot of power over migrant workers because the recruitment costs are high and the workers go into debt to work here.

“The more costs they incur, the more fear they will have,” he said.

Mr Tan said that many companies took on too many projects or tried to cut costs by hiring too few workers and skimping on safety measures even before COVID-19. He feels that it should cost the companies more to violate safety regulations, as human lives are at stake.

“We hope that instead of some administrative punishments, the authorities could consider more severe, stern actions for employers who are found to be not complying with safety rules.”

SAVING COSTS, LACK OF EQUIPMENT

Similar to what Mustafa described, at times, the workers want to be safe but don’t have the resources to do so.

Workplace safety experts CNA talked to said that safety starts from the planning and budgeting stage, and sometimes, it’s too late by the time inspections come around.

Experienced safety consultant Han Wenqi said that in his years in the industry, he has often come across situations where managers and supervisors tell him that the developer never budgeted for the safety precautions he thinks are necessary.

There are times when workers are wearing safety harnesses, but these are not connected to a lifeline, or the lifelines are hooked to a point that won’t support the worker’s weight. The workers are still at risk of falling “just with an extra full-body harness”, he said, adding that this “goes back to time and money”.

Not only is the safety equipment expensive, anchor points for the lifelines should be installed by professional engineers after making the necessary calculations, he said. But some work sites skip this step.

“They will control the expenditure by forgoing the safety provision or not even having a safety provision,” he said. He thinks this is linked to how projects are often awarded to the lowest bidder.

To counter this, he and other safety consultants suggest that all projects should have safety specifications stipulated in the tender documents.

Experts said that government projects tend to come with such specifications, while it varies for private projects. But it should be applied consistently to all construction tenders, so that the costs for safety equipment and precautions are included in the budget.

“If I were to give you a set of 50 pages of very in-depth and specific safety and health requirements versus a sentence: The successful bidder should comply with all the local, legal and other requirements. (There is a) big difference in between,” said Mr Han.

HARNESSING TECHNOLOGY

Another way to watch over the workers is with the help of technology - something which the authorities are pushing for.

In an adjournment motion on keeping workers and workplaces safe tabled in Parliament on Aug 1, MP Melvin Yong (PAP-Radin Mas) said that Singapore should leverage technology to detect and prevent workplace accidents.

Sensors and wearables can alert management when a worker deviates into a restricted area, or when a worker slips, trips or falls, allowing medical help to be dispatched quickly, said Mr Yong, who is also the assistant secretary-general of the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC). Big data and predictive analytics provide the potential of predicting accidents before they even happen, he added.

Invigilo is one company that is equipping companies with equipment and video analytics for workplace safety, and founder Vishnu Saran said that more enquiries are coming in from contractors for their products.

“The key thing is we want to provide complete coverage and continuous monitoring,” said Mr Saran.

“Secondly, what we’re doing with AI is to detect when these unsafe conditions or acts occur before they result in an accident.”

For example, many accidents involve falls from heights and workers being crushed by machines, so Invigilo’s technology can detect the absence of safety harnesses and barricades, and proximity to machines.

The safety manager gets an alert when these scenarios are triggered, and he can then correct the unsafe conditions before the accident happens, said Mr Saran.

Mr Goh, who is a consultant for Invigilo, said that a worker who was crushed by a crane could have been using the vehicle unsafely multiple times a day, every day, without incident for months. But it takes just one slip on an “unlucky day” for him to lose his life.

“But if you can see the trend that he's doing this work (unsafely), then you can predict the accident,” he said.

This is why some companies report “near-miss” incidents - where an unsafe act could have resulted in an accident. And now, CCTVs and AI can take over that role, said Mr Goh.

But that does not take the place of human responsibility.

MINDSETS AND ATTITUDES

Mr Lim Boon Khoon, principal consultant at Hazard Evaluation and Loss Prevention Consultants, said accidents happen because of human failure, which is linked to the workers’ and management’s attitude to safety.

“It is the attitude that shapes the behaviour of the people. And if you have bad behaviour, if you have poor attitude, accidents are likely to happen,” he said.

Safety training needs to go beyond theory and the technical aspects of accident prevention to identifying behaviour that endangers the workers, he said.

This sort of “behaviour-based training” requires workers to go back to their work sites and apply what they’ve learned to their daily work, he explained.

What happens after a workplace accident?

The Migrant Workers’ Centre (MWC) said that it assists workers and employers on a no-fault basis after an accident.

This is an example of what happened after an industrial accident where a fire broke out, resulting in the deaths of three migrant workers and injuring many others.

First Response:

As there were two companies involving two separate employers, MWC first contacted both employers to offer assistance and guide them in seeing to the urgent needs of the casualties.

This included advising them on signing the Letter of Guarantee required by the hospital to ensure medical attention and overseeing the safety of other workers on the premises.

MWC worked with the employer to notify the next-of-kin of the affected workers so that they were reassured that the employers are doing the needful.

Employer:

As the employer was overwhelmed with critical matters surrounding the incident such as assisting authorities with the investigation, MWC continued to provide additional support and guidance wherever possible, including advising the employer on the work-injury compensation process and how to submit the necessary documents.

MWC also provided a list of undertakers to help with bereavement and funeral rites, and guided the employer in the process to repatriate the remains.

Workers:

MWC and key representatives from NTUC visited the five workers warded in ICU to reassure them that their needs were being looked into and that the hospital would help arrange video calls with their families.

It also visited the nine uninjured workers who were housed at a temporary site to update them on the medical conditions of their co-workers. It also provided them with some essential items and daily necessities, as their personal belongings were damaged or lost in the fire.

Partnering with HealthServe, MWC also offered counselling services to the workers.

The organisation remained in close contact with the next-of-kin of the three deceased workers and updated them on what was being done. At the same time, it guided them in furnishing the documents that were required for the ex-gratia pay-out.

The Migrant Workers’ Assistance Fund also sent a token sum to the next-of-kin to help tide them through.

Since the incident, MWC said it has been periodically checking on the well-being of the recovering workers. Case officers continued to provide support to the victims, employer and next-of-kin, including ensuring that they received the compensation pay-out.

Other experts emphasised that attitudes stem from the very top - the company management has to take safety seriously, and they have to make this very clear to all the workers.

Besides introducing stiffer penalties for errant companies, MOM has said it will continue to hold companies as well as company leaders, supervisors and workers responsible for workplace accidents.

It is developing a code of practices for company directors' WSH duties, to provide clarity and practical guidance on how they can fulfil their legal obligations. This is now available for public consultation until Sep 8.

“The ones who are giving the resources and structure to the whole project are the developer and the main contractor, the management. Therefore, there has to be some accountability at that level … It sets the tone for the rest of development,” said Senior Minister of State Zaqy Mohamad at a safety forum organised by the Real Estate Developers Association of Singapore on Aug 25.

POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT

There are also existing measures for positive reinforcement, something which safety consultant Mr Goh emphasised.

“If you want someone to do something, you don't just punish him … he will just play a ‘cat-and-mouse’ game with you. But if you reward him for doing good, then he will want to do good,” said Mr Goh.

He pointed to programmes like BizSafe which help companies build workplace safety and health capabilities. BizSafe certification is a requirement for larger-scale contracts and tenders.

Said Mr Goh: “I would suggest the (workplace health and safety) council revisit these programme and see if programmes like BizSafe, CultureSafe should be revitalised.”

Mr Allen Tan, founder of United Tec Construction, a specialist prefabricated construction contractor with about 700 workers, agreed that it is better to motivate workers to want to be safe, than to take a purely punitive approach.

“Why don’t we encourage, motivate, give some incentives to people along the value chain … We need to cultivate a positive mind so that they can be motivated and take action,” he said.

His company ran competitions on safety performance between teams of workers and he gave his workers incentives like cash prizes or grocery vouchers.

MWC’s Mr Menon said that making safety part of workplace culture takes effort from everyone.

Besides making sure that workers are trained and well-rested, employers should implement a safe and easy reporting channel for unsafe workplace practices, he suggested.

This extends to developers and main contractors, who may need to be a bit more “understanding” about deadlines and penalties when there are extenuating circumstances like a shortage of workers, he said.

“You should not lose sight of the fact that the moment you drive people on deadlines, you increase the possibility of extra accidents occurring.”