Jakarta’s new governor Pramono faces his toughest test yet: Building a resilient city amid austerity

In an exclusive interview with CNA, Pramono Anung talks about steering Indonesia’s capital through budget cuts and climate threats even as the country turns its gaze towards Nusantara.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JAKARTA: When Pramono Anung entered the race to become Jakarta’s governor last year, the odds were stacked against him.

The veteran bureaucrat, who was Cabinet secretary during former President Joko Widodo’s term, had polled poorly in early surveys.

He went up against Ridwan Kamil, the charismatic former governor of West Java who was backed by President Prabowo Subianto’s super-coalition of 10 political parties, and retired police officer Dharma Pongrekun, who ran as an independent.

Pramono, 62, defied expectations and secured an outright win in the November 2024 regional election with just over 50 per cent of the vote.

Less than a year into his term, he has overseen the expansion of Trans-Jabodetabek bus corridors serving the capital and its surrounding regions, launched a “no-car Wednesday” policy for 62,000 civil servants, and tackled some of the worst flooding Jakarta has seen in recent years by quickly fixing dike breaches and deploying mobile water pumps.

But the governor of one of Southeast Asia’s busiest metropolises may need to defy the odds again with tougher battles lying ahead: Addressing Jakarta’s mounting urban woes amid sweeping austerity measures imposed by the Prabowo administration.

Indonesia is looking to slash funds allocated to help provinces and districts pay for their programmes and expenses from 919 trillion rupiah (US$55 billion) this year to 693 trillion next year.

Much of the money will instead be redirected to Prabowo’s flagship initiatives, including free meals for millions of schoolchildren and expectant mothers. The programme’s 171 trillion rupiah budget is expected to double next year.

This year, Jakarta received 27.5 trillion rupiah from the central government. In 2026, the amount will be reduced to 11.1 trillion rupiah, a drop of nearly 60 per cent.

As a result, Jakarta has been forced to trim its 2026 budget from 95 trillion to just over 80 trillion rupiah.

In an exclusive interview with CNA earlier this month at the Jakarta city hall, Pramono did not dwell on how he felt about the reduced central government funding when asked. Neither did he take questions on his party, the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P), or politics.

Instead, he focused on his plans for Jakarta and funding options for various projects.

“With the budget we have, we’re now exploring whether it’s possible to pursue creative financing,” Pramono said.

He elaborated on what he had in mind by referring to public-private partnerships and other innovative funding schemes to sustain critical infrastructure projects needed to mitigate Jakarta’s worsening floods, ease its notoriously crippling traffic and protect the city’s coastal areas from rising sea levels and land subsidence.

Urban planners CNA approached welcomed the direction set by Pramono.

“Jakarta needs to be more financially independent, especially with plans to move the capital to Nusantara by 2028,” said Yayat Supriatna, an urban planning expert at Jakarta’s Trisakti University.

Indonesia is relocating its national capital from Jakarta to the newly-planned city of Nusantara in East Kalimantan in response to Jakarta's urban woes.

The government hopes to have key government offices, including the presidential palace and parliament building, functional by 2028, with full build-out of infrastructure and institutions stretching out through to 2045.

Yayat, however, said Pramono must present clear business plans and compelling value propositions to attract investors and partners in Jakarta, especially given that similar ventures in the past have met with limited success.

30 PER CENT PUBLIC TRANSPORT GOAL

Cars and motorbikes outnumber people nearly two to one in Jakarta, which has long ranked among the most congested cities in the world.

According to the Greater Jakarta Transportation Authority, around 20 million people living in the capital and its surrounding suburbs of Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi commute daily to its business districts. Yet, only 22.1 per cent of them use public transport.

“If we can get that number to reach and stay at 30 per cent, I believe traffic congestion in Jakarta will decline significantly, and that’s what I’m pushing for,” Pramono said.

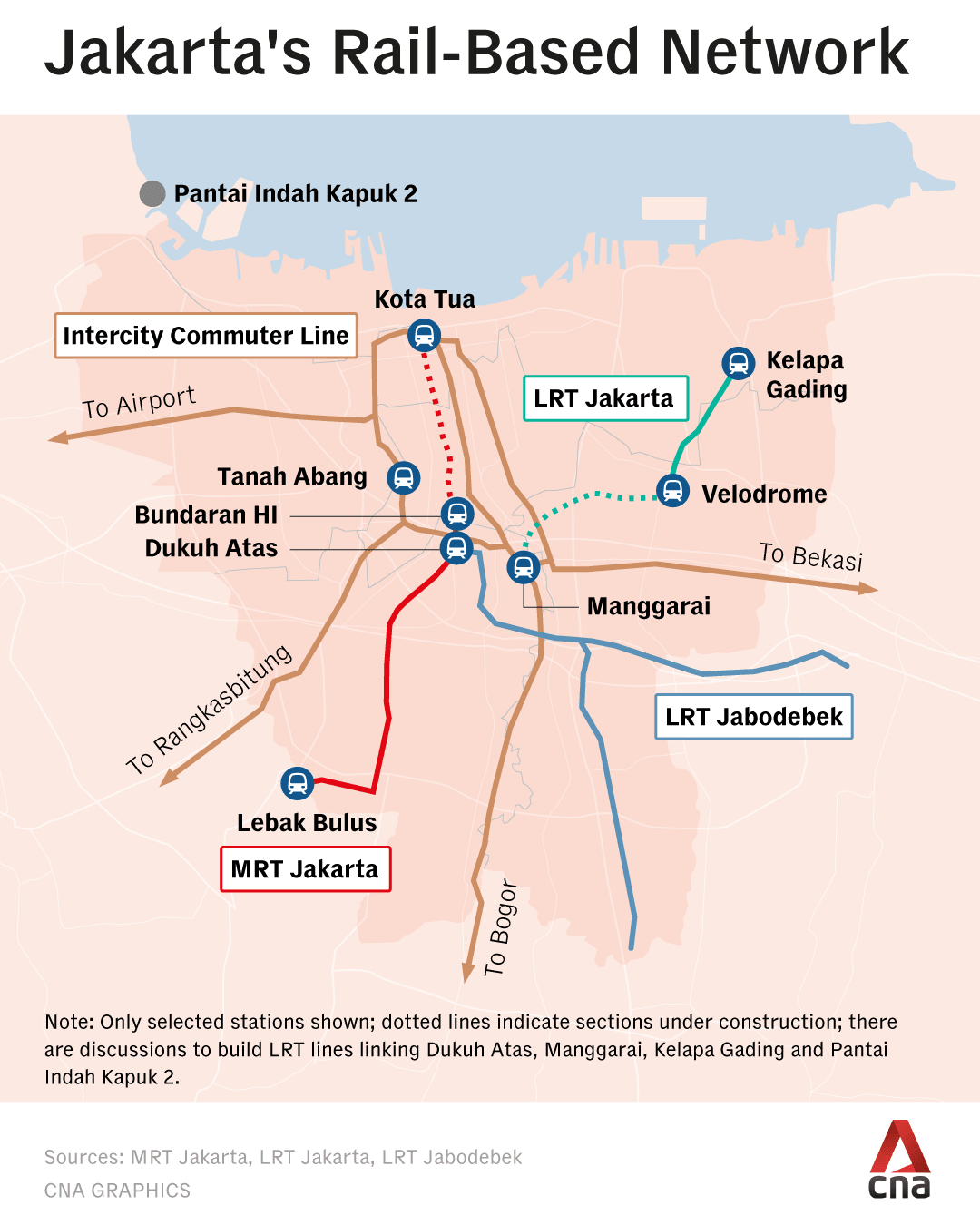

To achieve that goal, the city is currently adding 5.8km to its underground Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) line and extending its Light Rail Transit (LRT) network by 6.4km.

The 25.3 trillion rupiah MRT project - which is financed by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) - is set to complete in 2029 while the 5.5 trillion rupiah LRT extension, funded entirely by the city, is set to complete next year.

Pramono said the city is planning two new LRT lines: One that will connect the city-run LRT with the underground MRT, and another that would run along its mostly industrial northern coast.

“In the central and southern parts of the city, there are already many alternatives. But in the north, options are very limited, and toll road development there has been relatively slower than in the south,” Pramono said.

“I’m in the final stage of reviewing both options and will decide by the end of December which project to prioritise.”

The city is still calculating the cost of both projects, but one thing is certain: Jakarta will have to finance them on its own.

“I will invite investors to collaborate in developing these projects together,” Pramono said, without elaborating on what kind of partnership the city is offering or whether Jakarta already had investors lined up for the projects.

The city has experimented with property development as a way for city-owned transportation companies to make money. In January, PT MRT Jakarta was allowed to co-manage an ageing business complex at the heart of the city and transform it into a culinary and creative industry hub.

However, after an initial burst of enthusiasm, interest from tenants and shoppers has been tepid.

“MRT’s core business is transportation. It doesn’t yet have experience in property development,” said Yayat of Trisakti University.

Instead, MRT Jakarta should have invested in building facilities and schemes which not only support its core business but also generate revenue, he said.

“Why not build parking spaces so people can leave their cars and motorcycles and take public transportation? Why not come up with a bicycle sharing scheme so people can travel between the stations and their offices fast and comfortably?” he said.

A SEA WALL WITH MULTIPLE USES

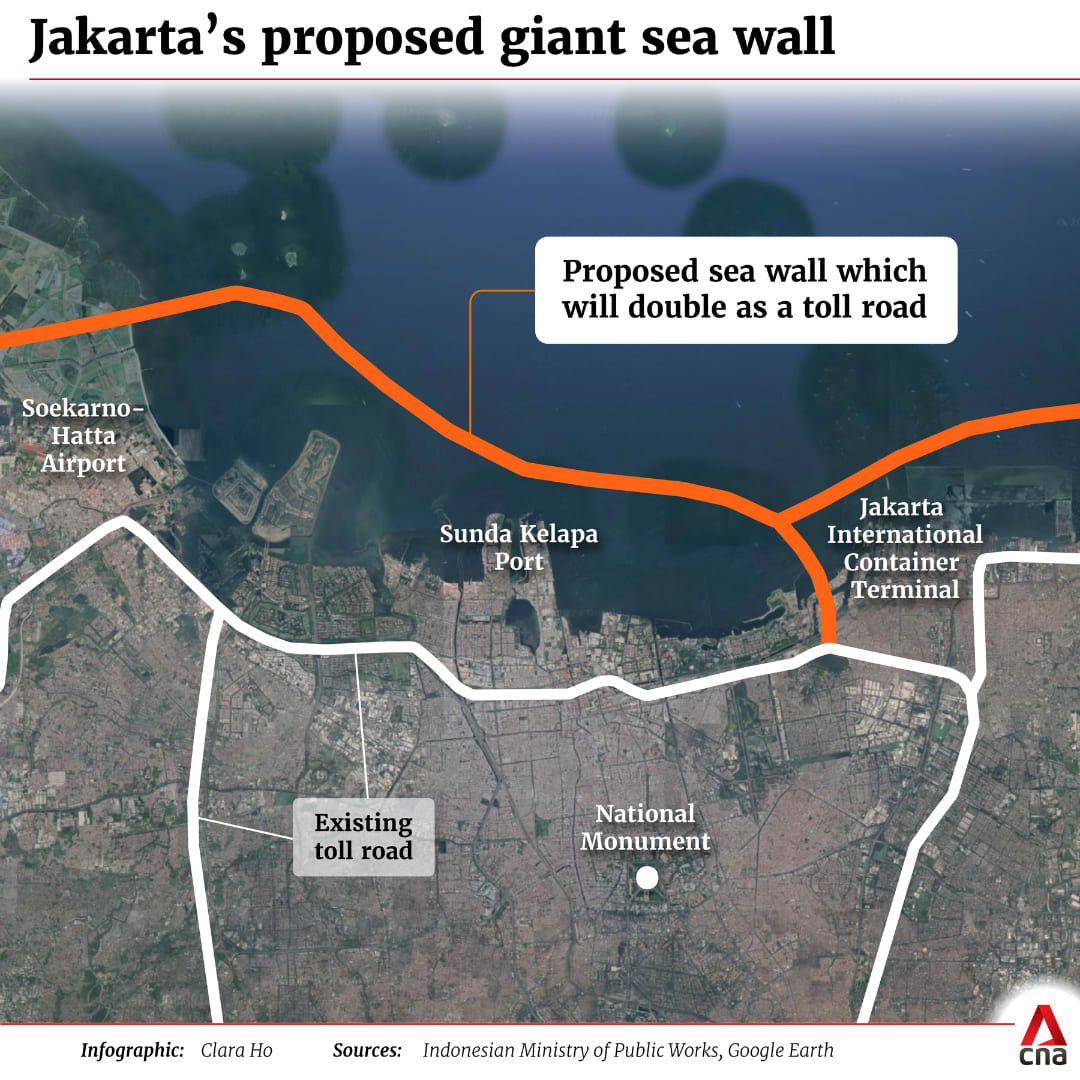

Another major infrastructural project in the capital is a giant sea wall to protect the city from coastal flooding and rising sea levels.

Jakarta has one of the fastest rates of land subsidence in the world, with some areas sinking by as much as 25 centimetres a year due to the over-extraction of groundwater.

Pramono said Jakarta is also seeking private sector partners to help finance its construction.

The US$8 billion coastal defence project is envisioned to stretch 46km along Jakarta Bay. Under current plans, Jakarta will finance 19km of the wall, while the central government covers the remainder.

“We won’t rely solely on the regional budget. This will be an investment project, and I’m confident investors will want to be part of it,” Pramono said.

The sea wall would not only serve as a barrier against flooding but also create a freshwater reservoir that could be used for drinking water, he said.

The structure itself could double as a toll road, while reclaimed land nearby could be developed into housing areas and resort zones.

“In many countries, reclamation projects have multiple uses and investors are eager to get involved,” Pramono said.

The idea of building a giant sea wall to both protect and redevelop the city’s coastline dates back to the 1990s, but progress has been slow and contentious.

The project’s enormous cost has long been a stumbling block and it continues to face strong opposition from environmental activists concerned about ecological damage as well as from local fishing communities who fear losing access to the open sea.

Some experts have also questioned whether a giant seawall is the right solution for Jakarta’s coastal woes, saying that it only offers a temporary fix if the overextraction of groundwater, which causes the city to sink, is not addressed.

Experts say Jakarta must also think creatively about financing infrastructure designed to prevent its 13 rivers from overflowing.

Flooding remains one of the most pressing challenges for the capital’s 10.6 million residents.

Some studies estimate that floods cause between US$125,000 and US$500,000 in damages every year. But some experts warned that this figure could rise as the population grows and climate change brings more extreme downpours.

“Most of the infrastructure we’ve built so far serves a single function like flood control,” said Firdaus Ali, chairman of the Indonesia Water Institute. “In the future, we need to integrate all water-based infrastructure so that it serves multiple purposes.”

For instance, dams could be designed not only to control floods, but also to irrigate farmland, generate hydroelectric power and serve as recreational areas, he said. “Some areas could even be used for electricity generation through floating solar panels.”

Achieving this vision would require stronger cooperation with neighbouring Bogor regency, where most of Jakarta’s rivers originate, Firdaus said.

“This could create a new revenue stream for Bogor, while Jakarta enjoys the benefit of reduced flooding,” he said.

CAN THE GOVERNOR DELIVER?

Before becoming governor, Pramono spent nearly a decade as Cabinet secretary under former President Widodo, a largely administrative role that kept him out of the political spotlight. Before that, he was a long-time PDI-P politician, known more for his quiet efficiency than charisma.

When PDI-P chairwoman Megawati Sukarnoputri first asked him to run for governor, Pramono admitted he was hesitant.

The role of Jakarta governor is one of the most prestigious seats in Indonesian politics and has been a stepping stone to a run for the presidency.

Survey institutes did not even include Pramono’s name among the potential candidates for Jakarta’s top job, and he was looking forward to slowing down after years in the executive branch.

“He was even seen as a backup candidate because talks between PDI-P and Anies (Baswedan) went nowhere,” said Adi Prayitno, a political analyst at Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University.

In the lead-up to November 2024’s regional elections, there had been much speculation whether Anies – a former Jakarta governor who made an unsuccessful bid for Indonesia’s presidency in February 2024 – would run again for Jakarta governor, but he struggled to find a party willing to back his re-election bid.

At the start of the race, Pramono lagged far behind in popularity against Ridwan, who was considered a rising star in Indonesian politics.

But Ridwan’s campaign faltered after his running mate, Suswono, made a controversial remark at an October rally suggesting that unemployed youths in Jakarta should “marry rich widows” to tackle poverty. The backlash was swift and within weeks, Pramono overtook the frontrunner.

He eventually won 50.07 per cent of the vote, while Ridwan and independent candidate Dharma took 39.4 per cent and 10.5 per cent, respectively.

Pramono’s victory - achieved with the backing of a single party, PDI-P - foreshadowed the kind of political challenges he would face as governor, particularly as PDI-P is one of only two parties that has not officially joined Prabowo’s governing coalition.

With the PDI-P holding only 15 of 106 seats in the city’s legislative council, analysts said Pramono could face challenges in getting strategic projects off the ground or come up with regulation changes and incentives to lure investors.

As for public opinion, a survey in June found 64.5 per cent of respondents expressing satisfaction with his performance 100 days into his term. Around 30 per cent said they were dissatisfied, while another 5.4 percent were undecided in the survey by the research arm of media company Kompas.

Observers describe Pramono as someone who listens to criticism but doesn’t shy away from sticking to his decisions.

One example was his Apr 30 decree barring civil servants from using private vehicles every Wednesday to reduce traffic congestion. He stood his ground despite grumbling from city employees and scepticism from critics.

“People thought this policy wouldn’t last,” Pramono said.

“But it’s been five months now, and I’ve remained consistent. In fact, Wednesday has become my favorite day - the day I look forward to the most, because it’s when I take public transport.”

He faced similar criticism when he decided to open several public parks for 24 hours a day.

“People were sceptical at first,” he said. “They worried the parks would be used for the wrong things. But over time, people realised they could enjoy the parks safely at any hour. Now, many communities even start their activities at night.”

A consistent approach may be exactly what investors need to see, analysts say.

“It builds confidence that he’s willing to do what’s necessary — and not let a few dissenting voices undo his policies,” said Firdaus of the Indonesia Water Institute.

“And the pressure is high for Jakarta to become financially independent,” he added. “Once Nusantara officially becomes the capital in 2028, the central government’s attention will inevitably shift away from Jakarta.”

But Pramono believes the central government will continue to play a role in Jakarta’s development. “Even when the capital moves, Jakarta’s role as the centre of Indonesia’s economy will remain,” he said.

He is preparing Jakarta for a rebrand even as it loses the title of Indonesia’s political capital.

“In 2027, when the city celebrates its 500th anniversary, the world will see a Jakarta reborn — driven by a new spirit and a renewed sense of purpose,” Pramono declared.