‘Like a bomb went off’: Fears linger over Indonesia’s 30,000 community-run oil wells amid efforts to regulate them

A new regulation issued in June aims to legalise these wells so long that they meet “good engineering practices” within four years.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

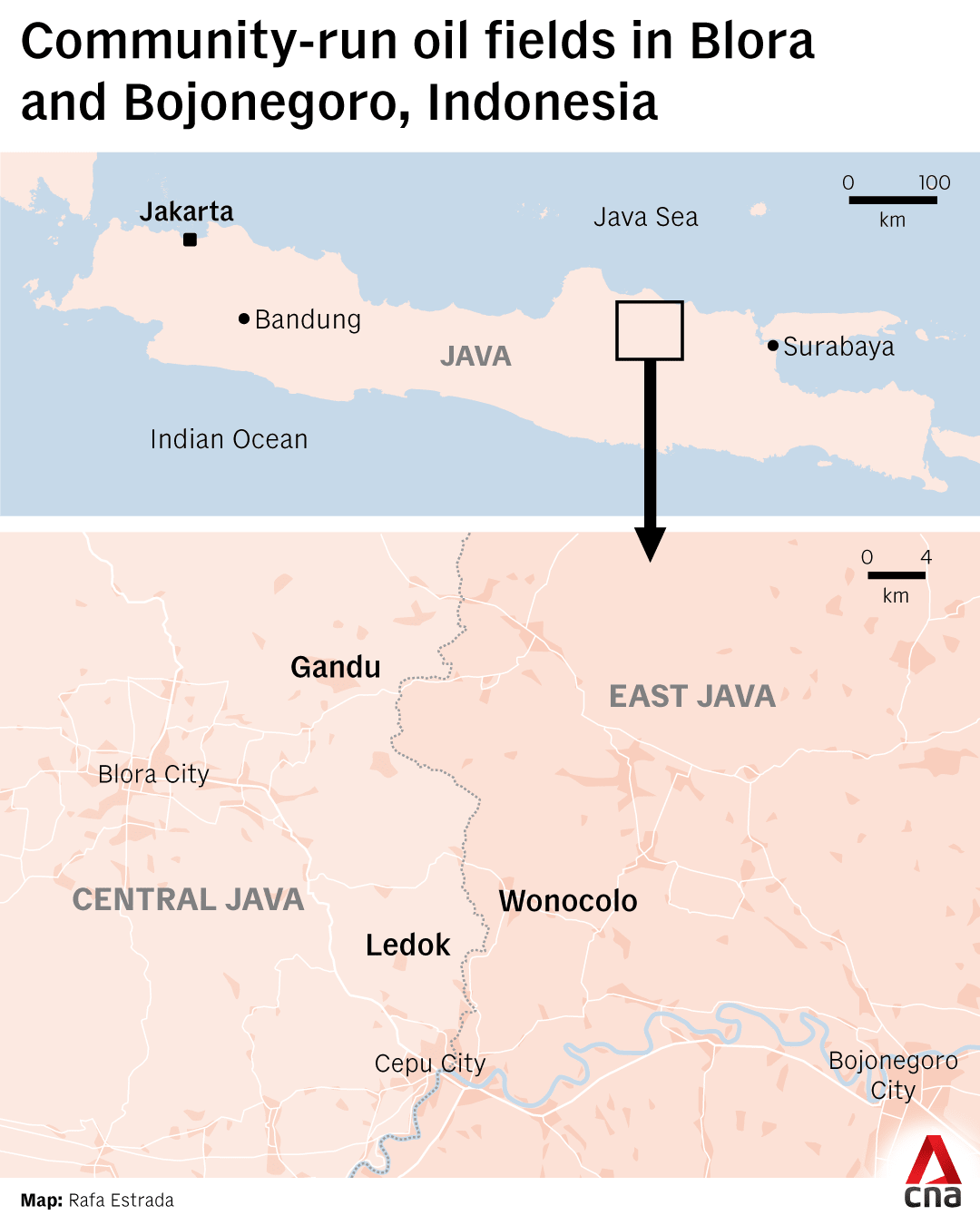

WONOCOLO, East Java: From a distance, the rolling hills and valleys of Wonocolo resemble the backdrop of a post-apocalyptic film.

As far as the eye can see, the trees that once blanketed these slopes have been replaced by three-legged towers - wooden logs lashed together with hemp rope, like skeletal sentinels jutting out of the ground.

Up close, the scene is even more surreal in this small East Javan village. The ground is dark and slick, streams are choked with iridescent oil and the air is thick with the smell of petroleum, the fossil fuel that is both Wonocolo’s economic lifeline and its undoing.

Oil wells have been a feature in the village for more than a century, first operated by Dutch colonial rulers followed by a succession of private and state-owned companies. Since the 1970s, they have been operated by locals with little training and rudimentary equipment.

Wonocolo is far from unique. Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources estimates there are at least 30,000 of these so-called community-run oil wells scattered across the country.

“They conduct drilling activities with little to no safety precautions or regard for the environment,” said Putra Adhiguna, managing director of the think tank Energy Shift Institute. “As a result, blowouts and oil spills are rampant."

These wells operate without permits, he added, but the government has long turned a blind eye because of their role in sustaining local economies.

That stance is now shifting. On Jun 3, the Energy Ministry issued a regulation allowing artisanal oil wells to operate legally provided that they meet yet-to-be-determined safety and environmental standards in four years' time.

“(The Indonesian government) is trying to find a middle ground. By legalising the activity, the government hopes these wells can be better monitored and regulated,” Putra said.

“But oil extraction is not like other forms of mining. Even licensed oil and gas operations run by official companies ... carry major risks. If such operations are run by ordinary people without sufficient resources, it’s bound to become chaotic.”

In August, a fire at an oil well in Central Java's Blora regency killed four people, injured two and forced the evacuation of about 800 people.

Firefighters struggled to put it out for seven days. The burning well was “unusually wide” and it was difficult to “shut off the source of the fire”, Blora’s disaster mitigation agency head Muhammad Chomsul reportedly said.

OIL RUSH GOING STRONG

Oil was first discovered in the area in 1870 by Dutch engineers, who found oil about 10km southwest of Wonocolo, in the village of Ledok in Blora regency.

By the early 20th century, dozens of oil wells had been set up in what is now known as the Cepu oil block, which straddles the border of Central and East Java.

“If the Dutch found oil on your property, they would certainly grab your land and leave you homeless. If you keep the oil for yourself, you will be accused of stealing, sent to jail or shot,” said 64-year-old Ledok resident Tarmadi, recalling tales from the colonial era he had heard from his late father.

When Japan invaded Indonesia in 1942, the wells were plugged, ransacked or set on fire by retreating Dutch troops who did not want them to fall into enemy hands.

After Indonesia gained independence, several private companies and state-owned enterprises tried to manage a number of these wells.

“Not all (wells) were profitable enough for big companies,” Tarmadi told CNA, adding that the wells ignored by corporations ended up in the hands of locals.

Villagers with some experience in the oil industry began restoring these abandoned wells. Rusted pipes were replaced with new ones while wooden towers were raised over the shafts.

At the top of each tower, a pulley was hung to lower and raise a steel plunger that collects the oil. In the early days, these pulleys were powered by sheer muscle. Later, villagers repurposed old truck engines to do the heavy lifting.

Wonocolo resident and oil driller Laman told CNA that at first, there were only a handful of community-run operations in his village. But the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis changed everything.

As factories shut down and millions lost their jobs, many returned to their hometowns to try their luck in the oil fields.

“People weren’t just restoring old dormant wells, they were digging new ones too,” said Laman, 72, as he watched his workers scramble to fix a leak in his well’s ageing shaft pipes.

Today, there are 425 wells in Wonocolo, a village of just 2,000 people spread over 11 square kilometres. Each well produces around 500 litres of crude oil a day, according to Laman.

Most of the crude is sold to a refinery operated by state oil company Pertamina, which buys at about 30 per cent below market price.

Even so, well owners can earn between 2 million and 4 million rupiah (US$130 to US$260) in revenue per day, a huge sum in a regency where the minimum salary is 2.5 million rupiah per month.

“But you spend a lot of money to keep these wells running. The older they get, the more expensive to maintain them,” Laman said.

From as low as a few hundred dollars, the cost of running the wells can balloon to tens of thousands of dollars if there is a major leak which requires entire shaft pipes to be replaced.

Meanwhile in Blora, a regency of 2,000 square kilometres, there are some 4,000 wells spread across dozens of villages.

“These wells are providing our residents with jobs and economic growth. Every year, our economy grows by upwards of 7 per cent,” Blora regent Arief Rohman told CNA.

By comparison, Indonesia’s economy expanded by 5.12 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter of 2025.

NEW POLICY AIMS TO RAISE SAFETY STANDARDS

The new regulation provides a legal umbrella for communities to operate their own oil wells.

The rules, however, specify that only existing wells - those originally drilled by large corporations but later left idle or abandoned - qualify. In addition, well owners must join a cooperative or register as a small or medium-sized enterprise.

Communities are also required to follow what the government calls “good engineering practices”.

“For years, there have been many accidents. They carried out drilling activities without regard for the environment. What the Minister (Bahlil Lahadalia) wants is to regulate these practices so such incidents can be avoided,” energy ministry spokeswoman Dwi Anggia told CNA.

Statistics on community-run oil well accidents are hard to come by because they existed in a legal grey area and often operated in secret. The latest blowout occurred on Sep 12 in Banyuasin regency, South Sumatra, killing five people. Police are still investigating the cause of the blowout.

The worst incident occurred on Apr 25, 2018 when a well in Aceh exploded as dozens of workers were extracting oil from it. Twenty-eight people were killed and dozens more suffered severe burns.

Legalising the practice, Dwi said, will allow major oil contractors and companies to formally work with traditional miners - training them in safety procedures, environmental protection, and introducing modern technology to support their operations.

The regulation comes as Indonesia seeks to boost its oil production to one million barrels per day by 2030.

Oil output peaked in the 1990s at about 1.6 million barrels per day. Since then, production has declined so sharply that Indonesia became a net oil importer in 2003. The current national output is about 580,000 barrels per day.

Dwi said the government is still defining what “good engineering practices” will entail, while also formulating programmes to help communities meet them.

“There will certainly be technical guidelines issued to regulate all of this,” she said, adding that the government is giving artisanal oil miners four years to comply.

“If during those four years they fail to comply with good engineering practices, then their wells will be shut down. And if there is evidence of criminal violations, law enforcement action will be taken.”

Some miners welcomed the new regulation. “We no longer have to worry about breaking the law. It puts us in a better position to negotiate prices with refineries, and we can even apply for loans. Everything will finally be above board,” said Wonocolo resident Laman.

But others remain cautious as many questions remain unanswered.

“What exactly will the requirements be? Will they be realistic for small miners like us, or only accessible to those with huge capital?” asked Tarmadi of Ledok, Blora.

NEW WELLS BEING DUG IN HOPES THEY WILL BE ALLOWED

Regional governments across Indonesia are currently racing to catalogue old and idle wells – no simple task in a landscape where some lie hidden deep in forests or perched on remote hills, reachable only by miles of bumpy dirt tracks.

But as officials vet these old wells, new ones are being dug in the hope they, too, will be recognised as “existing”.

The deadly inferno that broke out in Blora’s Gandu village on Aug 17, Indonesia’s Independence Day, was reportedly drilled earlier this year and had been operating for only a week.

“It was like a bomb went off,” recalled 44-year-old Supriyati, a mother of two who lived just metres from the site.

At the time, she could feel the ground shaking beneath her feet. Shockwaves ripped through her home, collapsing walls and leaving half the house in ruins.

She vividly remembers neighbours screaming and running in every direction as flames clawed at the sky.

Government officials have since plugged the well and ordered all villagers to return to their homes. But Supriyati still refuses to sleep in what remains of her house, choosing instead to live with relatives more than a kilometre away.

“I’m still worried … it could erupt again without warning,” she said.

Energy ministry spokeswoman Dwi Anggia said the regulation only applies to existing wells drilled in the past, before the new rules came into effect.

“If there are new wells dug after this regulation was issued in June 2025, then law enforcement action will be taken,” she told CNA.

Blora regent Arief Rohman said there are at least three more wells in Gandu that officials suspect were dug after the regulation was enacted.

Like the one which blew up, these wells were dangerously close to people’s homes and authorities have since shut them and arrested those operating them.

“We are taking precautions to prevent this from happening again. Wells located in unsafe areas must not be allowed to operate – they will not be legalised and have to be closed,” he said.

“We understand that many people want to depend on this sector. But they must follow regulations, the licensing process, the safety standards. The community is traumatised by this incident. They do not want it to happen again.”

Arief added that officials in Blora are combing the regency to look for wells which violated the regulation. “So far we have only found the ones in Gandu,” he said.

Experts said the incident serves as a reminder of how dangerous the practice can be in the hands of untrained extractors, including those working in wells that have operated years before the regulation was issued.

Even with the new government policy, Putra of Energy Shift Institute questioned if the authorities could ensure operations at community-run oil wells consistently meet safety and environmental standards.

“If the government cannot even stop new wells from being dug, how can it possibly monitor all 30,000 if they are formally registered?” he said.