Commentary: How Singapore should tackle food resilience after dropping '30 by 30' goal

The struggles of high-tech farms demonstrate that building a resilient food system requires more than engineering, says urban farmer Bjorn Low.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Last week’s announcement by Minister for Sustainability and the Environment Grace Fu marks a turning point in Singapore’s strategy for food security.

The familiar “30 by 30” target, which envisioned Singapore producing 30 per cent of its nutritional needs by 2030, is being replaced with more focused goals: 20 per cent for fibre and 30 per cent for protein by 2035.

As of 2024, 8 per cent of the fibre consumed in Singapore was homegrown, and for protein, the figure was 26 per cent.

It is a moment that made me pause not just as someone working in urban farming, but as someone who has watched our food systems evolve from the ground up.

For years, we leaned heavily on high-tech farming as the silver bullet. But the recent struggles of high-tech farms have reminded us, sometimes painfully, that building a resilient food system requires more than engineering. It requires humility, ecological wisdom and a willingness to rethink what “local food” really means.

WHEN TECHNOLOGY MEETS BIOLOGY

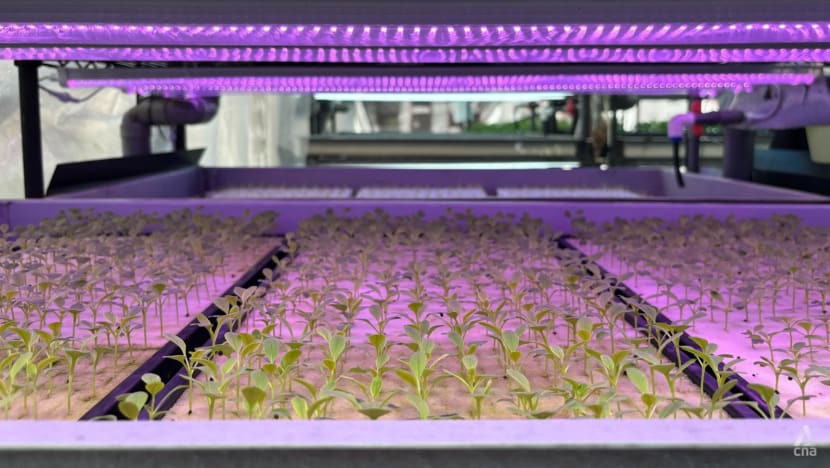

Vertical farms once felt like the future. Neat rows of plants, precisely controlled lighting, automated systems. I remember walking through some of these spaces feeling as if I had stepped into a laboratory rather than a farm.

But the closures of farms like Growy and I.F.F.I have forced many of us to confront a difficult truth: Farming does not bend easily to technological ambition.

Energy use remains one of the biggest barriers. A small 30 sq m indoor farm can use more than 13,000 kWh each month. That comes to about S$5 of electricity for every kilogram of produce.

And even then, the system can be undone by a single point of failure. I have seen a cooling system malfunction destroy an entire crop cycle. I have also seen disease sweep through a tightly enclosed grow room long before anyone realises something is wrong.

Farming is an ecological craft that depends on instinct, experience and living systems. Software updates cannot fix nutrient imbalances. Sensors cannot replace biological resilience. And although indoor farms need skilled engineers, horticulturists and data specialists, agricultural wages often cannot keep pace. This leads to turnover, gaps in knowledge and constant retraining.

Government programmes will help lower some of these barriers and attract new talent. But none of this will succeed unless people are willing to buy and support local produce.

WHY LOCAL VEGETABLES HAVE NOT TAKEN OFF

Walk into a supermarket and you will spot the bright red SG Fresh Produce logo on certain packs of vegetables. Our farms are offering more varieties than ever. But for many shoppers, local vegetables remain a “nice to have” rather than a necessity. I often hear people say: “Kailan is kailan. What is the difference?”

Yet we do not say that about eggs. More Singaporeans will choose local eggs if they can. They are seen as fresher and safer, and people believe the difference is worth paying for. Local egg production has grown steadily because of this gradual shift in perception.

Vegetables are different because their advantages are not as widely understood. Few people realise how quickly leafy greens lose nutrients after harvest, particularly Vitamin C and many B vitamins. When produce spends days travelling through long cold chain routes, the nutrient loss is significant.

Local vegetables avoid much of this. They are harvested close to home and often eaten the same day. They taste better because they are fresher. They are more nutritious because time has not stripped away their value. And you can often see the farmers and farms behind them. These stories need to be told more clearly.

Beyond consumer behaviour, we need to treat food resilience as part of our national safety net. Long-term commitments from hospitals, schools and caterers would give farms the stable demand needed to invest in staff, systems and strategic planning.

A HYBRID APPROACH FOR A NEW ERA

Singapore’s updated “Food Story 2” approach is built on four pillars: grow local, diversify imports, stockpile and build global partnerships. It is a solid base. But the real leap forward will come from blending appropriate technology with regenerative design, circular resource use and community growing.

This is where I see a quiet but powerful shift happening.

Every week, I meet residents who are turning balconies into herb gardens, growing leafy greens in corridor planters or tending allotment plots with neighbours. These are not hobbyists passing time. They are people reclaiming a sense of agency over their food and reconnecting with the land in small but meaningful ways.

These small spaces will not replace commercial farms, but they build something just as important: food awareness, community bonds and a shared sense of responsibility. They bring people closer to the food they eat and make fresh produce part of everyday life.

Imagine a Singapore supported not only by a few large facilities, but by thousands of growing spaces scattered across the city. Rooftops, void decks, balconies and community gardens forming a resilient, distributed food web. That is a system that is not only productive but also personal.

FROM FOOD SECURITY TO FOOD SOVEREIGNTY

Ms Fu said that strengthening resilience requires us to “learn from experience, innovate and take collective action”. This signals a deeper shift from food security to food sovereignty, which is not only about supply, but participation, dignity and agency.

We can grow plenty of food without ever strengthening our connection to it. But when communities get involved when children harvest what they planted, when seniors share composting tips, when neighbours exchange herbs across corridor railings, something changes. Food becomes not just a commodity but a shared resource.

If Singapore’s water story was built on engineering ingenuity, our food story will need to be built on ecological imagination and community participation. We transformed water scarcity into a strength by rethinking our relationship with a vital resource. We can do the same with food by grounding our approach in care, creativity and collective action.

Bjorn Low is Founder of Edible Garden City, an urban farming social enterprise.