Commentary: Wake-up call for Asia - how urban challenges are rooted in rural hardships

If more isn’t done to alleviate rural hardships in Asia, they will eventually perpetuate overburdened cities, youth unemployment and urban poverty, says Seoul National University’s Edo Andriesse.

SEOUL: In April, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned diplomats about the severe lack of progress in global efforts to end poverty and hunger, fight inequalities, and tackle climate change.

“Unless we act now, the 2030 Agenda will become an epitaph for a world that might have been,” Mr Guterres said.

There are 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) with 169 targets - of which all UN member states have committed to support - but the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastating “triple crisis” of climate, biodiversity and pollution, amplified by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, have hindered progress, he said.

As a result, just 12 per cent of the SDG targets are on track, while progress on 50 per cent is weak and insufficient to meet the 2030 deadline.

Worst still, extreme poverty is higher than in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic, and hunger is back at 2005 levels. These sober statistics should be a wake-up call for the international community to do more. But how can we improve this dire situation given the increasing pressure on cities?

ASIA’S CENTURY OF GROWTH AT RISK

The 21st century has been said to be Asia’s century of growth. China has become a major growth engine, India is steadily making strides as an economic powerhouse, and Southeast Asian nations, notably Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, are also growing at a rapid pace.

By 2050, Asia is expected to account for more than half of global GDP.

One of the most profound drivers of change has been urbanisation. In the last couple of decades, millions of people migrated from rural areas to cities in the hope of a better life. In 2020, 51 per cent of Asia’s population lived in urban areas, up from less than 20 per cent in 1950.

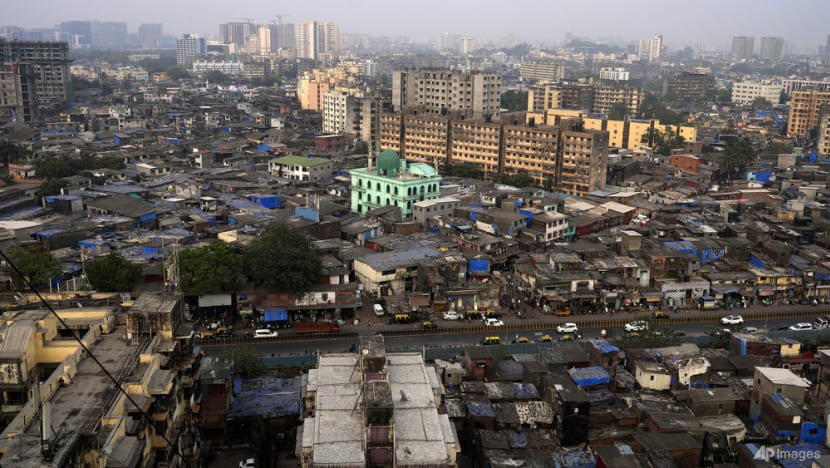

On the one hand, cities are sites of cosmopolitanism, innovation, splendid architecture, and extreme wealth where billionaires spend their money.

On the other hand, many migrants in Asia end up in slums, cannot find a decent job in the formal sector, and find it next to impossible to reach middle-class status.

The persistence of slums in middle-income countries such as India, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand threatens Asia’s rise this century. Housing conditions are still poor for 500 million people in the Asia Pacific region, stable jobs are hard to find, uncontrolled landfilling remains pervasive, and during monsoon seasons slums are at risk of being flooded.

These socioeconomic and urban environmental challenges slow down the trajectory towards the formation of a broad-based middle class. Moreover, it can also lead to social unrest, protest and national paralysis.

AVOIDING A MERE RELOCATION OF POVERTY

Rising economic and political power aside, real progress in Asia will only come if we pay more attention to the plight of rural communities.

According to the International Fund for Agricultural Development, about 80 per cent of the world’s extremely poor people live in rural areas.

“Hunger, poverty, youth unemployment and forced migration - all have deep roots in rural areas,” it said in a report.

The global rural population is around 3 billion people. With more than half, or 1.8 billion rural people in Asia, we cannot afford to assume that solving urban problems will automatically reduce poverty, inequality, and vulnerability.

The challenges large metropolises like Karachi, Ho Chi Minh City and Shanghai are facing are intimately linked to rural hardships.

This is mainly due to the fact that many migrants are insufficiently prepared when migrating to large cities. Migrants with relatively low educational attainments and without connections find it hard to find stable jobs, navigate the big city, and could experience emotional loneliness.

Therefore, if we seek a balanced and inclusive process of urbanisation without extreme urban inequalities, we also need to pay more attention to the plight of fishers and farmers. Otherwise, rural-urban migration merely ends up in a relocation of poverty.

Another reason to invest more in the countryside is the vital function it has in bad times. During shocks, migrants return to their original villages. This happens when urban employment rapidly declines, as seen during the Asian Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic.

If rural communities are impoverished, they cannot function properly as socioeconomic safety valves and vicious cycles emerge. And as the world has become more unpredictable, we need to create more options to enhance livelihood security, not only in urban but also in rural areas.

URBAN CHALLENGES AND RURAL HARDSHIPS INTERTWINED

Since 2004 I have conducted research on rural development in Southeast Asia, most notably in the Philippines. Together with collaborators, I investigated the rural hardships communities are continuously facing.

Farmers, smallholders, and peasants are at risk due to droughts, lack of land, changes in commodity prices, and difficulties bringing their produce to markets.

Small-scale fishers need to grapple with higher food and fuel prices, higher ocean temperatures and the continuation of large-scale fishing operations depleting the world’s fish stocks. Efforts to find alternative income sources have been initiated, yet it remains challenging to achieve long-term success.

In the Philippines, the government has promoted cultivating seaweed to reduce overfishing and expand incomes. It has worked in islands like Southern Mindanao and Palawan, but not everywhere. In areas where seaweed is not thriving, people eventually return to fishing and find jobs elsewhere.

Another trend is increasing inequality within rural communities. Some fishing boat owners and landowners can increase their assets rapidly while the poorer fishers and farmers are sometimes forced to sell boats or land to make ends meet.

Again, family members consider migration to the city as a solution, but often get stranded in dire circumstances. If educational attainment is low, temporary migrants end up having insecure jobs in the informal economy.

These insights, as well as related observations from Thailand and India demonstrate that despite the ongoing process of urbanisation, poverty reduction and responding to climate change cannot be solved without a proper focus on rural communities.

If more isn’t done, rural hardships will eventually perpetuate overburdened cities, youth unemployment, and urban poverty.

Dr Edo Andriesse is a Professor in the Department of Geography at Seoul National University.