Commentary: How Xi Jinping withholds promotions and power says a lot about China’s new political order

The president’s pattern of withholding Politburo seats is showing on both the military and civilian sides of China’s Communist Party, says Wang Shengyu from the Asia Society Policy Institute.

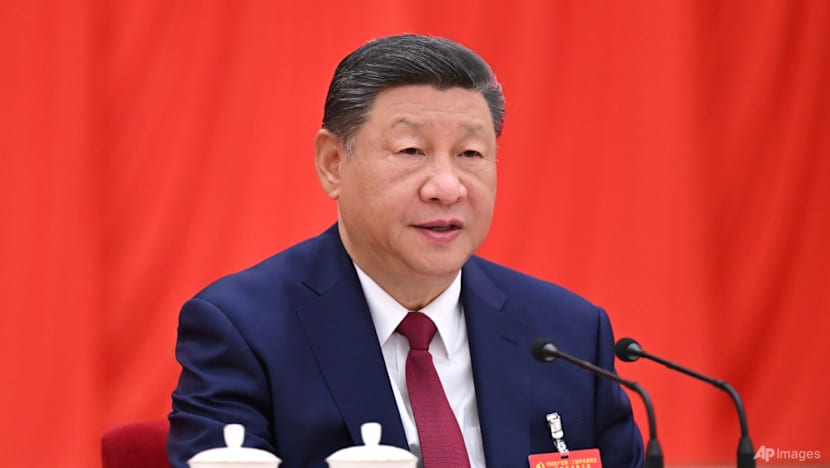

In this photo released by Xinhua News Agency on Oct 23, 2025, Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks during the fourth plenary session of the 20th Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee in Beijing. (Xie Huanchi/Xinhua via AP)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

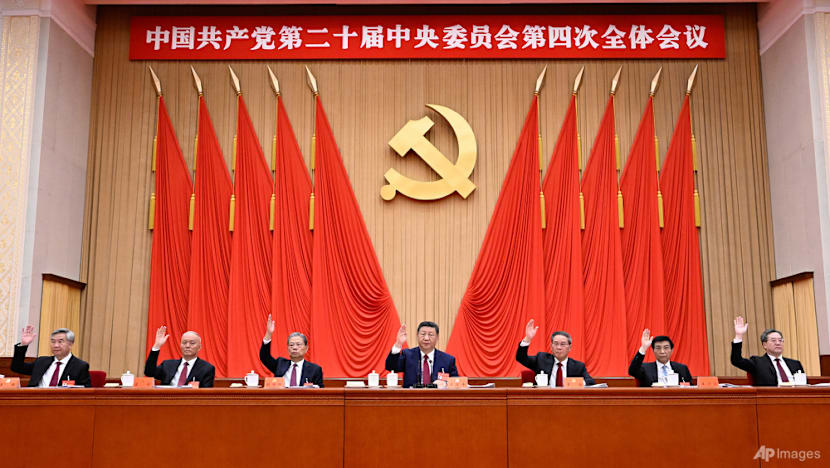

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Virginia: China wrapped a key political meeting just a week before President Xi Jinping’s Oct 30 bilateral with United States President Donald Trump and other key APEC engagements in South Korea. Considering how successful the APEC summit was for him, Mr Xi clearly arrived from a position of strength.

But the most significant thing to happen at China’s Communist Party's Fourth Plenum in October is what didn’t happen.

After a year of surprising disciplinary purges, there was an expectation that Mr Xi would restore a sense of order. While the plenum did fill vacancies on the Central Committee by promoting alternate members, the party leadership made a deliberate choice not to fill a crucial seat in the once 24-member Politburo.

This calculated absence was not an oversight. Rather, it reflects the defining feature of a new political logic under Mr Xi.

Is a smaller Politburo the new norm? Are old rules, like guaranteed seats for senior military leaders or age-based retirements, now up for reconsideration?

These questions point to a deeper change taking shape in Beijing’s top ranks: Xi Jinping wants to verify the loyalty of cadres before giving them full status upgrades.

PROMOTIONS AND PARTITIONS

To understand the shift taking place, look no further than the case of General Zhang Shengmin.

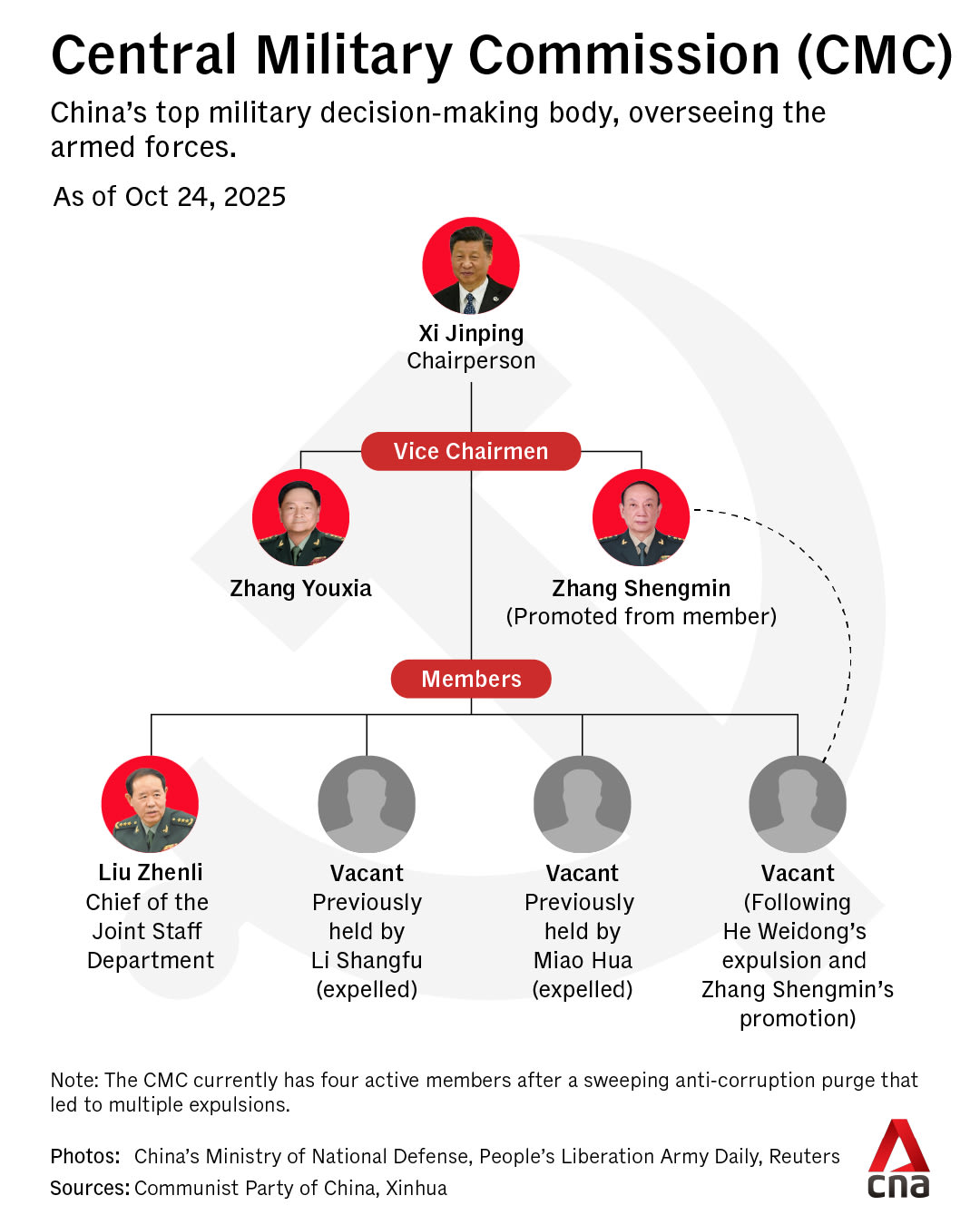

In the days before the plenum, General He Weidong, who had been a Politburo member and one of two vice chairs of the powerful Central Military Commission (CMC), was expelled from the Party. At the plenum, General Zhang was promptly promoted to fill the crucial CMC post, a clear sign Mr Xi trusts him.

But the corresponding status, a seat in the Politburo, which has been standard for CMC vice chairs for decades, was pointedly withheld. The message is clear: Political status and new appointments are no longer automatically linked.

An even more subtle and revealing signal followed the plenum. Zhang Shengmin was conspicuously absent from a key meeting of the Standing Committee of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection that disseminates the plenum’s outcomes, which strongly suggests that his power as a senior figure within the party is constrained.

General Zhang was elevated to one of the most powerful military positions in the country, given vast responsibility and greater recognition for rooting out corruption within the People’s Liberation Army. And yet, isolated from the cross-cutting role in the party disciplinary apparatus, his jurisdiction now seems narrower.

This is Mr Xi’s playbook in action: promote but partition.

TRUST, BUT VERIFY

This new pattern of withholding Politburo seats is also evident on the civilian side of the CCP.

On Jul 1, Chen Xiaojiang was appointed Party Secretary of Xinjiang, and he seemed a likely candidate to be added to the Politburo. After all, every Xinjiang party chief since the early 2000s has held that status. But, the Fourth Plenum also passed without his promotion.

On the surface, this decision doesn’t seem to make sense. Mr Chen’s strength lies in ideological and ethnic governance, precisely the areas the Party now prioritises in Xinjiang. Since the early 2000s, Beijing has expressed continued concerns of “terrorism” and “separatism” in the region.

Mr Chen also appears to have backing at the highest of levels. In September, Mr Xi visited the region for its 70th anniversary – a powerful endorsement of both Xinjiang's importance and the Xinjiang party chief. Still, his formal status upgrade to the Politburo has been delayed, in what appears to be a display of Mr Xi’s attempt to bifurcate power between high-ranking officials and the Politburo.

His predecessor, Ma Xingrui, illustrates the other side of this new reality. Under his watch, Xinjiang saw major infrastructure and high-tech investments and efforts to integrate with the Belt and Road Initiative. But his departure was abruptly announced, and he currently holds no known post, despite retaining his Politburo seat.

In effect, Mr Ma is now a senior cadre without a job, an apparent form of soft sidelining. It is in stark contrast with his predecessors who transitioned into defined roles after leaving Xinjiang and evident of a new political reality.

XI’S NEW POLITICAL ORDER

These developments reflect a deeper drift from what began even before the 20th Party Congress.

In 2022, ahead of the congress, the party conducted an unusually broad round of personnel consultations compared to the 19th Congress, soliciting opinions from 283 civilian and theatre command leaders and 35 top military leaders. Mr Xi also personally held one-on-one talks with 30 principals to solicit views.

The result was a smaller, 24-member Politburo (down from 25), a symbolically even number that eliminated the theoretical possibility of a tie-breaking vote and projected a carefully balanced image of unity and consensus across systems and sectors – all loyalists of Mr Xi.

But three years later, that institutional balance is shifting. Politburo vacancies aren’t being filled per previous norms, and appointments no longer synchronise with political status.

Status is provisional, withheld until performance and loyalty are proven. Delay keeps cadres uncertain, sharpens incentives and denies any faction the chance to build momentum.

If anything, political loyalty to Mr Xi is now just a basic need and bare minimum for survival in Chinese elite politics; what truly counts now is the ability to deliver outcomes that advance his agenda.

As the 21st Party Congress approaches in 2027, these departures from established norms signal that Mr Xi is steadily rewriting the rules of elite politics, leaving the structure, composition, and conventions of China’s top leadership more uncertain – and more firmly under his control – than at any time in recent memory.

Wang Shengyu is a research assistant at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis.