Commentary: We have to stop calling some jobs ‘low skilled’

Freeing ourselves of these labels might help young people to think more creatively about the future, says the Financial Times’ Sarah O’Connor.

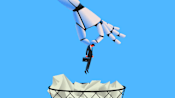

LONDON: Even from a continent away, it is possible to hear the gasps from Silicon Valley as software developers begin to realise that they have very successfully automated away one of their own core skills.

Aditya Agarwal, the former chief technology officer at Dropbox, summed up the mood in a recent post: “It’s a weird time,” he wrote. “I am filled with wonder and also a profound sadness . . . We will never ever write code by hand again. It doesn’t make any sense to do so. Something I was very good at is now free and abundant.”

But if senior developers are feeling disoriented, spare a thought for the poor teenagers who are trying to decide which skills to invest in for the future.

There are plenty of opinions out there. Anthropic president Daniela Amodei says “studying the humanities” will be more important than ever. Others argue that interpersonal skills will be key.

And then there are those who reckon the safest way to go is to swerve white-collar work altogether and develop manual skills such as electrical installation or plumbing.

EVERYONE IS CLUELESS

But the truth is, nobody really has a clue. If anyone might know, it would probably be Francesca Borgonovi, head of skills analysis at the OECD Centre for Skills.

But she is refreshingly honest: “I don’t know what to tell my kids to study,” she told me. “At the end of the day, I’m just as clueless as anybody else. And that could be a very good thing.”

How so? Every now and then in the history of work, she says, there have been ruptures: moments when structural economic changes shook up which skills were most economically valuable, and people who weren’t necessarily at the top of the old social order had a sudden opportunity to advance.

After World War II, for example, there was a big technical push that reshaped demand. In concert with better access to higher education, that enabled people like her mother and father to rise from poor backgrounds to good jobs in a computer company and a university respectively.

WHAT SKILLS WILL BE IN ECONOMIC DEMAND?

But in recent decades, the social order has ossified around the pre-eminence of roles that require high levels of education and cognitive skill.

As Adrian Wooldridge put it in his book The Aristocracy Of Talent in 2021, “the meritocratic elite is in danger of hardening into an aristocracy which passes on its privileges to its children by investing heavily in education, and which, because of its sustained success, looks down on the rest of society”.

Economists have contributed to this with their habit of describing certain jobs as “high-skilled” (and other jobs as “low-skilled”) when what they actually mean is “jobs that require skills that the market currently values highly”.

Humans possess lots of different types of skills, from quantitative and cognitive to fine motor, creative, emotional and problem-solving.

Anyone who has watched an experienced carer at work would know that this job requires high levels of certain skills in order to be done well. (That doesn’t mean that every care worker possesses them, of course, just as not every manager is actually skilled at managing people.)

Which skills are set to be in high economic demand after this current rupture might be different to the ones we have grown used to.

Therefore, it is a very good time to stop applying the terms “high-skilled” and “low-skilled” to entire occupations. Indeed, it is well past time, since it was always both offensive and a category error.

FREEING OURSELVES OF LABELS

Freeing ourselves of these labels might also help young people to think more creatively about the future.

Take the convergence on STEM skills, for example. For students taking three A-levels in 2025, the most popular combination of subjects was biology, chemistry and maths, according to education professor Mike Watts (with maths the most popular of all).

There’s no reason to think these skills will become obsolete, especially if you love them and are really good at them. But it no longer makes sense to study certain subjects purely because you think they will provide you with a “good” job (either in terms of pay or social standing).

Indeed, it’s likely that being mediocre at something you don’t really like and only went into because you thought it would be “safe” is probably the fastest way to get replaced by a machine.

Your teachers don’t know what skills will be most valuable in the future. Your parents don’t know. Even the OECD’s head of skills analysis doesn’t know.

There is a certain liberty in that. My advice to young people is simple: forget the “high” and “low” labels, lean into what comes naturally, study what you love and hope for the best.