Commentary: Malaysia opposition leader Muhyiddin pulls off shrewd political move with '24-hour resignation’

There are several possible reasons why Muhyiddin Yassin changed his mind a day after vowing to step down as Bersatu party president. But the best answer might not be the most obvious one, says James Chin, Asian Studies professor at University of Tasmania.

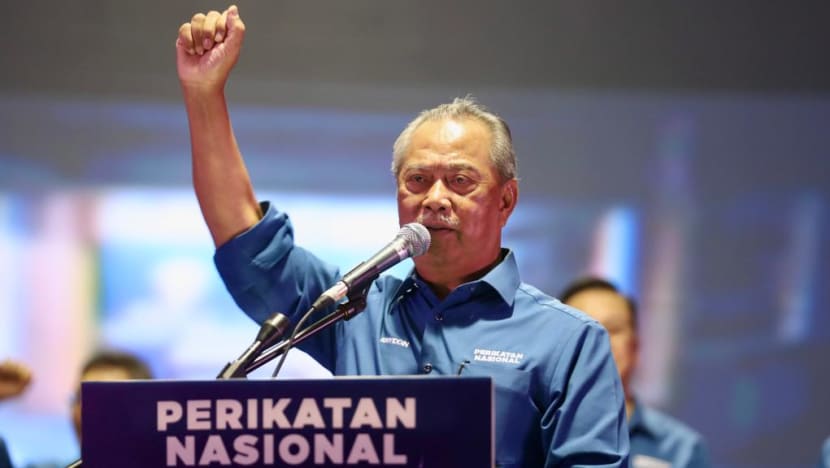

Former Malaysian prime minister and Perikatan Nasional (PN) chairman Muhyiddin Yassin at a coalition event on Jun 24, 2023. (Photo: Facebook/Muhyiddin Yassin)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

HOBART: Twenty-four hours after the surprise announcement that he would step down as president of his party, Malaysia’s de facto opposition leader Muhyiddin Yassin did a complete U-turn.

On Saturday (Nov 25), the former prime minister said he would defend the presidency of Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) in its party elections next year. Bersatu leads the Malay-majority Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition, which also includes Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS).

Muhyiddin said he really wanted to leave, but that his wife told him to stay for another term.

Why all the high drama? After all, on paper, Muhyiddin looks secure in his position as Bersatu chief. He is one of the party founders and a political heavyweight.

Perhaps most importantly, PN did extremely well in the six state elections in August. The opposition made major inroads in Malay-majority seats and increased their share of the Malay votes by about 10 per cent.

TESTING WATERS WITH BERSATU PARTY MEMBERS

The most obvious answer, and widely circulated in Kuala Lumpur political circles, was that Muhyiddin was testing his real support in Bersatu.

Immediately after his announcement on Friday, Bersatu’s Supreme Council held an emergency meeting and unanimously rejected Muhyiddin Yassin’s decision.

What most people forgot was that Muhyiddin had used this same tactic earlier this year.

In early March, he said he had offered to resign after being charged with multiple counts of corruption and money laundering. Bersatu’s Supreme Council rejected it, on the basis that the charges were political prosecution by Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s administration.

Cynics would argue that by getting the Supreme Council to refuse his resignation now, Muhyiddin has secured a full-throated vote of confidence and ensured that there will be no challenger to his power at internal polls in 2024.

PERIKATAN NASIONAL’S PUBLIC FACE FOR NEXT GENERAL ELECTION

Another possible explanation is Muhyiddin was trying to avoid a split in the party. It is open knowledge that there are political tensions between Bersatu deputy president Faizal Azumu and the party’s secretary general, Hamzah Zainuddin.

Both men are gunning for the top job and by making sure the number one position is unavailable for another term, this may cool down the political temperature in the party.

The kind version is simply that Muhyiddin is the only PN leader who can appeal to the voters as a prime minister.

The biggest party in PN is not Bersatu, but PAS with 43 parliamentary seats compared to Bersatu’s 31. It is widely accepted that PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang is an unsuitable candidate to be prime minister.

On top of his considerable health issues, Mr Abdul Hadi is a polarising figure in Malaysian society. In recent years, he has made many controversial statements against minority communities, especially the Chinese, which are widely seen as racist and unbecoming of a senior political figure.

PN needs Muhyiddin as its public face if they hope to recapture Putrajaya in the next general election.

BEST EXPLANATION FOR MUHYIDDIN’S STUNT

Perhaps the best explanation of why Muhyiddin pulled the stunt has to do with Bersatu itself. Since PN’s victories in the state elections, Bersatu has become weaker politically, rather than stronger.

Between October and November, four Bersatu Members of Parliament (Kuala Kangsar, Labuan, Gua Musang and Jeli) have publicly declared support for Mr Anwar’s government while insisting they remained loyal to Bersatu.

Such announcements were shocking to some, given parliament had passed the anti-hopping law in 2022 which discourages MPs from switching parties. MPs will automatically lose their seat if they defect to another party.

But here lies the loophole: Lawmakers retain their seat if they switch allegiances without quitting their party. In other words, as long as they remain Bersatu’s MP on paper, they are free to support any other party or political leader. If Bersatu sacks them, they are legally able to join a new party of their choosing.

The irony was not lost when many people pointed out that it was Bersatu who did not plug the loophole when the anti-hopping law was drafted.

Former law minister Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar said that the loophole was known and accepted by all parties when the bill was passed. He further claimed that he had insisted on including a clause that MPs would automatically vacate their seat if they were to go against the stand of their respective parties in parliament, but this was rejected by PN.

More Bersatu MPs may jump ship now that it is clear the anti-hopping law does not work in practice. There are rumours that another three or four opposition MPs may switch their support to Mr Anwar before the end of this year, with as incentive simply the ability to access government funding for their constituency.

This would have increased political pressure on Muhyiddin to take political responsibility for losing the MPs.

But after the Bersatu Supreme Council’s swift rejection of his decision to step down, Muhyiddin has confirmation that he is safe politically.

ANYTHING CAN HAPPEN BETWEEN NOW AND 2027

Muhyiddin’s “24-hour resignation” was a shrewd political move. He has emerged stronger politically after the annual party congress when it could easily have turned against him.

More importantly, he is now in pole position to retain the presidency in Bersatu internal elections next year. If he wins without a challenger, then all he has to do is wait for the next general election, due by 2027 at the latest.

If PN wins that election, then he will break Mahathir’s record as a second-time prime minister.

The bad news, of course, is that Malaysian politics is wholly unpredictable. Anything can happen between now and 2027.

But Muhyiddin’s political stunt ensures that no matter what happens over the next four years, he will remain a major player in Malaysian politics.

James Chin is Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania and Senior Fellow at the Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia.

.png?itok=imeZiA5w)