Commentary: Malaysia judges make their mark with Najib verdict, but will it last?

The Federal Court’s upholding of the conviction of former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak has restored confidence in the key national institution. But the country’s democracy faces stern challenges ahead, says a researcher.

SINGAPORE: On Aug 31, while effusively celebrating Malaysia’s 65th Merdeka Day, citizens also took heart at the recent demonstration of independence by the judiciary. Just a week prior, the Federal Court – the country’s apex court – upheld former prime minister Najib Razak’s conviction for corruption in the SRC case. The case was the first of five involving the 1MDB scandal.

The unanimous ruling, delivered by Chief Justice Tengku Maimun, has restored confidence in a key national institution. Malaysia’s democracy breathes a bit easier – and stronger. The five-member panel of four Federal Court justices and the Chief Judge of Sabah and Sarawak quelled latent concerns that Najib’s High Court verdict, already upheld by the Court of Appeal, could actually be overturned by the Federal Court.

In the end, it was “a simple and straightforward case of abuse of power, criminal breach of trust and money laundering”. The evidence of guilt was overwhelming; the wisdom and courage of judges prevailed over Najib’s lawyers’ attempts to disrupt and delay the proceedings.

Where predecessors may have capitulated to political pressure, this Court stood its ground.

LINKS TO 2018 GENERAL ELECTION

Some have linked the judicial landmark of Aug 23 with another momentous day: The 14th General Election (GE14) of May 9, 2018. Opposition politicians have been reminding Malaysians that their vote matters.

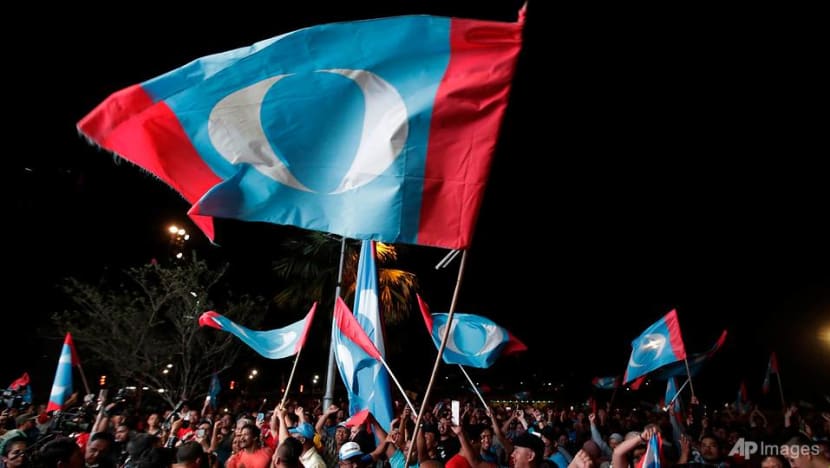

GE14 saw a groundswell of support for change and a fierce protest vote against Najib and the Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition’s six decades of rule. The electorate gave Pakatan Harapan the reins of power, including a mandate to prosecute corruption at the highest levels and bring about democratic reforms.

But it is worth stressing that judicial independence did not just sprout; it has been budding for the past decade.

The Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC), established in 2009 by then prime minister Abdullah Badawi, sought to restore dignity and credibility to the Courts then tainted by political interference and scandals involving top judges. All five judges presiding over Najib’s appeal were appointed by the prime ministers who have served since 2018, upon recommendation of the JAC (with the King’s final seal).

However, we must be tempered in crediting GE14. The change of guard in the judiciary may have coincided with political turning points, but resulted more from the operational need to fill vacancies due to high turnover. Most judges become sufficiently senior and qualified for the Federal Court in their sixties, only to clock out at the mandated retirement age of 66 years and 6 months.

REFORM IS FAR FROM COMPLETE

Malaysia’s judicial consolidation shows that the road to reform is long, often winding, and far from complete. BN’s reach into the machinery of government was broad and deep in the days running up to its historic electoral defeat in May 2018.

The GE14 experience is instructive in more ways. While evoking the heights that Malaysia scaled, it is also important to recall that in the run-up to polling day, the Election Commission (EC) had flagrantly gerrymandered electoral boundaries to make various constituencies more Malay-populated and presumably more advantageous to BN.

In Selangor, the country’s richest state, the number of seats in which Malay voters comprise more than 60 per cent of registered voters was increased from eight to 11, while the number of “mixed” seats – where no ethnic group constitutes a majority – was reduced from nine to four.

These border redelineations defied demographic and administrative logic, but made political sense. The EC also set Wednesday as polling day to maximise inconvenience and throttle voter turnout. Hours after the results had circulated in the public domain, the EC refused to certify victory for Pakatan Harapan.

Democracy prevailed not because the electoral system got better, but despite the devious schemes of BN-captured institutions. However, the evidence of the incumbent’s loss overwhelmed efforts to subvert the electorate’s will.

Election Commissioner appointments under PH have overseen cleaner and fairer elections, but there has been no formal change in the EC’s independence nor its accountability to parliament. The integrity of Malaysia’s elections still rests on the discretionary decisions of the persons holding the trust.

Since GE14, Malaysia has registered some bipartisan democratic reforms. Most consequentially, voting rights have been extended to 18- to 20-year-old citizens, putting into effect a law passed in July 2019.

Recently, an anti-hopping law was passed, prohibiting elected representatives from switching parties. At the same time, political proceedings underscore the impact of diligence in working out democratic reform.

Parliament’s longstanding and often inert Public Accounts Committee (PAC) has been consistently prominent in the past four years because of the persons involved, most notably the PAC chair and Ipoh Barat MP Wong Kah Woh. Institutions matter, but people deliver.

MOVING FORWARD FROM NAJIB’S IMPRISONMENT

The backlash from Najib’s imprisonment has started. The crescendo of demands for Parliament to be dissolved and Najib to be pardoned, led by UMNO President Zahid Hamidi who is on trial for numerous corruption charges, will subject democracy to stern tests ahead.

How Malaysia fares moving forward depends on vigilance by all of society, but the branches of government have their distinct roles to play.

First, within the judiciary, the JAC can be further empowered by making its decisions binding, rather than the current advisory role that still leaves room for the prime minister’s discretion. The onus should be on the prime minister to accept the JAC’s recommendation – or to provide grounds otherwise.

Broader representation in the JAC, currently dominated by senior judiciary figures, would also allow for scholarly perspectives to weigh in and avoid biases of peer evaluation. Past proposals to raise Federal Justices’ retirement age, to 70 or even higher, should be revisited to allow for longer tenure. For a profession that demands experience and seniority, it is decidedly premature to exit at 66.5.

Second, many other institutions should take the cue from the judiciary in performing their public duty. The Attorney-General’s Chambers’ prosecution of corruption must forge on, especially involving high-profile personalities, unwaveringly pursuing justice while allaying fears that such cases may be dropped before judicial verdicts.

In the prison system, Najib should be granted protection, not privilege. The Pardons Board will also have to weigh petitions with abundant wisdom and rectitude.

Third, parliament needs to show maturity and resist efforts to force its dissolution and trigger an untimely general election, while faithfully checking the executive, particularly with regard to the ongoing littoral combat ship procurement scandal. For all the strife and expediency that has sullied parliament, the Dewan Rakyat has also shown glimmers of constructive bipartisanship.

Will the judiciary’s stand have lasting impact? Unlike the Najib verdict, what happens next is anything but simple and straightforward. The question is whether Malaysia pivots for good.

Lee Hwok-Aun is Senior Fellow of the Regional Economic Studies Programme and Co-coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Programme at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. This commentary first appeared on the Institute’s blog, Fulcrum.