Commentary: Singlish is so much more than ‘broken English’

As Singapore enters its seventh decade, we face a choice: Keep treating Singlish as something to fix, or embrace it as the heart of who we are, says Daniel Chan of NUS.

Singlish slang makes an appearance in the National Day Parade 2015. (Photo: Xabryna Kek)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: My primary school teacher once scolded me for using “broken English” and ending a sentence with “lah”. That same afternoon, I watched my sister order chicken rice at the hawker centre in a mix of Mandarin, Teochew and English: “Uncle, wo yao kueh png, no bone. Dowan chilli.”

Nobody batted an eyelid. It was just how we spoke. That contrast between what’s acceptable in class and what’s normal everywhere else has puzzled me ever since. Why was the way we spoke treated as a flaw?

Singapore’s bilingual education policy is often told as a success story. Since the 1960s, English has been promoted as the language of economic progress, and Mother Tongue languages for cultural grounding. In 2020, 74.3 per cent of literate residents surveyed in the population census were at least bilingual, up from 70.5 per cent a decade prior.

But we don’t compartmentalise English or our mother tongue in our daily lives. We live in the spaces between and beyond them.

A study by the Institute of Policy Studies and CNA, commissioned on Singapore’s 60th birthday, found that Singaporeans associate Singlish with their national identity. Of the respondents who agreed Singapore has a national identity, 31.3 per cent said Singlish and the languages spoken here define who we are.

What if what we’ve been calling “broken” all along is actually an asset that we have never fully recognised?

THE MULTILINGUAL SINGAPOREAN MIND

Singaporeans don multiple hats to engage with the world. Academics speak at conferences; business leaders confer with overseas peers or even testify before foreign lawmakers – all in precise, global English. But back home, they switch seamlessly to Singlish with friends and family.

Linguists call it translanguaging, drawing from a single fluid mental pool of languages. Even when proficiency levels across languages are uneven, the brain’s executive functions are strengthened by the very act of blending languages, registers and tones.

It is like improvising music to the mood instead of playing to a fixed score. That same mental flexibility, expressed through language, is what equips us for the cultural agility the 21st century demands.

Languages evolve. Every language you now call standard was once a hybrid: Old English emerged from Anglo-Saxon dialects; Old French arose from Vulgar Latin mixed with Gaulish and Frankish.

The Singlish I grew up with was steeped in Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese. Phrases like “bo jio”, “sabo king”, “sian half” were loaded with cultural meaning and shared experiences. But as those dialects fade, so too does a certain version of Singlish.

Younger Singaporeans still pepper their speech with “lah”, “leh” and “walao”, but new influences from fandom and pop culture are slipping in, from the Korean “Hwaiting!” (Good luck!) and “oppa” (older brother), to the Japanese “kawaii”(cute) and “chotto matte” (wait a bit).

Crucially, the natural enrichment of language through borrowing presents social benefits. Studies show informal exposure to multiple languages helps children develop perspective-taking and communication skills.

More than just multilingualism, this is 21st-century cultural fluency.

POLICY VS PRACTICE

Despite this linguistic richness, the public discourse can feel stuck in time. Campaigns like “Speak Good English” suggest that clarity should be prioritised over culture.

But the idea doesn’t match our lived reality anymore. Singlish isn’t substandard, but a fully formed and legitimate variety of English born in Singapore.

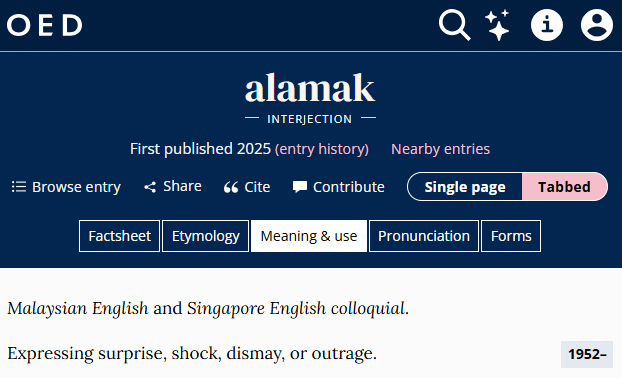

Even the Oxford English Dictionary seems to have made up its mind: It has been adding expressions used in Singapore and Malaysia, like “lepak”, “blur” and “shiok”. In March, “alamak”, “tapau” and others were included. Oxford noted that borrowing “untranslatable words” from other languages fills a lexical gap and that loan words sometimes become part of a speaker’s variety of English.

If even the canons of English recognise our way of speaking, maybe it’s time we did too.

OUR NATIONAL ASSET

If we are serious about multilingualism, in practice and not just on paper, we need to rethink our unique blend of English. To achieve this, I suggest three simple shifts.

First, retire the tired “good vs broken” narrative.

A community workshop participant once told me “My English not good one, you don’t mind ah?” – then spoke articulately and confidently. Her apology shows how deep our linguistic insecurity runs. We must stop judging language by native norms and start valuing clarity and contextual awareness.

Second, teach about Singlish, not against it.

While standard English remains essential for global exchange, understanding Singlish helps students see how context shapes meaning, and how local identity and global communication coexist. Classroom discussions could unpack what Singlish is, why it matters and how it’s evolving.

Third, harness Singlish for cognitive and intercultural growth.

In my own French language classroom, I’ve had students ask whether preceding “comme d’habitude” (as usual) with “ben”, a word only used when speaking, is akin to adding “lor” in Singlish.

“Ben comme d’habitude.” “As usual lor.” Same function, different form.

The instinct to compare across languages signals analytical flexibility and stronger intercultural empathy. These life skills matter in today’s workplaces and globally connected communities.

RETHINKING OUR LEGACY FOR SG60

As Singapore enters its seventh decade, we face a simple but profound choice: Keep treating Singlish as something to fix or recognise it as part of who we are.

The confusion many of us felt growing up, speaking one way at home, and another in school, wasn’t about poor English. It was about being taught to doubt the way we naturally communicate.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Celebrating Singlish and recognising its value can narrow the divide.

To speak like a Singaporean is to move fluently between cultures – with instinct, empathy, and adaptability. That’s not a weakness, but a legacy worth carrying forward.

Dr Daniel Chan is Senior Lecturer (French) at the Centre for Language Studies, and Assistant Dean (Undergraduate Matters) at the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore.