analysis East Asia

China is set to host a record-sized SCO summit. Can it turn symbolism into substance?

China’s hosting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit from Aug 31 to Sep 1 offers a leadership showcase, but rivalries in the bloc may limit what it can deliver, analysts say.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

BEIJING: As wars rage on and the global order frays, China is turning to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to project itself as a stabilising force and champion of multilateralism - positioning itself as a counterweight to an increasingly unilateralist United States, say analysts.

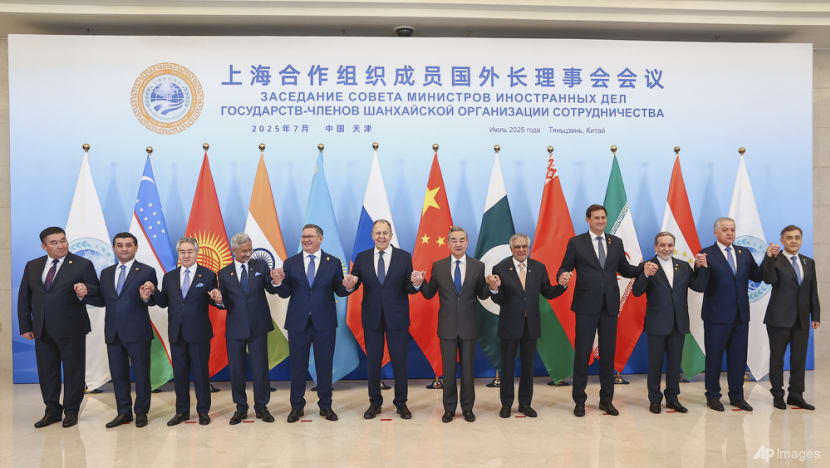

The upcoming summit in Tianjin, set for Aug 31 to Sep 1, will be the bloc’s largest to date - a forum bringing together powers at war or often at odds, including Russia, Iran, India, Pakistan and China.

But even as it offers Beijing a high-profile platform to advance its multipolar vision and burnish its global leadership credentials, observers warn that internal divisions could blunt those ambitions, reducing the gathering to optics and rhetoric over substance.

Hosted by China for the first time since 2018, the Tianjin summit is expected to draw more than 20 heads of state and 10 leaders of international organisations.

The guest list includes Russian President Vladimir Putin, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian and United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

This year’s summit will also be notable for the high-level representation from Southeast Asia.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto and Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh are all scheduled to attend in person, alongside leaders from Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

A SUMMIT OF SCALE AND SYMBOLISM

Formed in 2001, the SCO evolved from the “Shanghai Five” - a loose forum created in the mid-1990s by China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to resolve border disputes and build trust along their frontiers.

In the two decades since, it has expanded to 10 full members, now including Uzbekistan, India, Pakistan, Iran and its newest entrant, Belarus. The bloc also counts Afghanistan and Mongolia as observers, along with 14 dialogue partners ranging from Türkiye and Sri Lanka to Cambodia and Myanmar.

For Beijing, hosting this year’s summit is about scale and visibility, with analysts saying the message it hopes to project is one of clout, influence and convening power in a turbulent global climate.

“When Russia or India hosted in the past, the summits were relatively modest. This time, China has poured far greater diplomatic resources into the event,” Lin Minwang, vice dean of Fudan University’s Institute of International Studies, told CNA.

He added that the symbolism matters too, pointing out that the SCO is the only international organisation named after a Chinese city - in this case, Shanghai.

“(It is) a distinction that explains why Beijing has consistently attached special importance to the bloc and its chairmanship,” Lin said.

At the same time, observers say China wants to use the summit to highlight its touted embrace of multilateralism and its role as a global stabiliser, in contrast to what it sees as an increasingly unilateralist United States.

Beijing is looking to frame the SCO as part of a broader web of networks and platforms offering alternatives to Western-led frameworks, said Alejandro Reyes, a senior fellow at the University of Hong Kong’s (HKU) Centre on Contemporary China and the World.

“At a time when the US seems to be burning bridges everywhere, China is creating more and more different frameworks, more coalitions of the willing,” he told CNA.

The current geopolitical climate - from wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, to rising tariff battles initiated by Washington - could give Beijing’s message greater traction within the SCO, say analysts.

China’s last hosting of the SCO summit in 2018 coincided with US President Donald Trump’s first term between 2017 and 2021, a period marked by rising tensions with Washington but relatively less global upheaval than today.

“The 10-member organisation may be more receptive than normal given the military conflicts involving Iran and Russia, and the United States’ tariffs strategy,” Jonathan Ping, an associate professor at Bond University, told CNA.

Beyond the summit, China’s Sep 3 military parade to mark 80 years since the end of World War II will also be closely watched, particularly to see which SCO leaders go on to attend, offering a glimpse into shifting alignments and the depth of their diplomatic engagement with Beijing.

DIPLOMACY UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

Scale and symbolism aside, analysts say the true test of the summit lies in the interactions among its key leaders and in how Beijing manages to navigate the competing interests within such a sprawling and diverse bloc.

Together, the SCO’s members, observers and dialogue partners span nearly half the world’s population, a quarter of its landmass and around a quarter of global GDP.

“The SCO’s expansion has made it both distinctive and unwieldy,” said HKU’s Reyes. He further noted that the bloc has become a rare forum where powers often at odds - including China, Russia, India, Pakistan and Iran - all sit at the same table.

“The questions you have to ask are - what’s the dynamic between Russia and China, what’s the dynamic between China and India, and then how do all the others in the mix navigate that kind of ecosystem?”

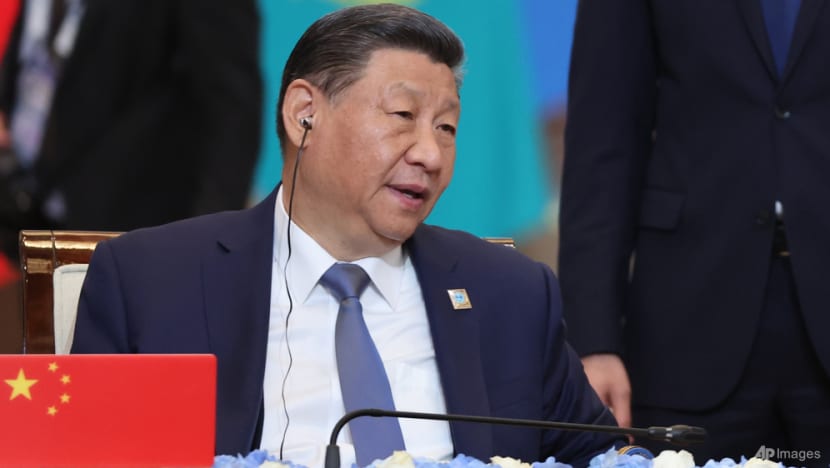

The most closely watched interactions at the SCO summit in Tianjin will be among Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russia’s Putin and India’s Modi, say analysts.

For Moscow, the summit is a chance to show it is not diplomatically isolated despite its war in Ukraine. For Beijing, it is a delicate balancing act - reaffirming its “no-limits” strategic partnership with Moscow while avoiding the appearance of full alignment with the Kremlin’s war, observers note.

But expectations remain modest. “It is a very delicate dance that Russia and China do,” said Reyes.

“Friendship without limits is just rhetoric rather than reality.”

As for New Delhi, the meeting could open space to recalibrate ties with Beijing after years of tension, even as its strategic partnership with the US continues to deepen.

Modi’s attendance is particularly notable. It will mark his first visit to China in seven years - the last being in 2018 for the SCO summit - following the deadly border clashes at Galwan Valley in 2020 that effectively froze bilateral ties.

Analysts say his presence reflects both India’s shifting calculations and China’s determination to use the SCO as a platform for dialogue.

“This summit gives China a rare opportunity to project unity and potentially solve old grievances,” said Bond University’s Ping, noting that Beijing may seek to capitalise on strains in US-India ties.

Washington’s doubling of tariffs on goods from India to as much as 50 per cent took effect on Wednesday (Aug 27), adding friction to the bilateral relationship. The US has said the higher duties are in retaliation for New Delhi’s continued purchases of Russian oil, which it argues help finance Moscow's war in Ukraine.

“The United States’ attempts to cut Russia’s oil income from India, and Pakistan’s recent dispute with India, give China’s diplomats an opportunity to consolidate influence by aligning with India,” Ping said.

In a further sign of thawing ties, Beijing and New Delhi recently agreed to resume direct flights - suspended since the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 - and strengthen business links.

Even so, Lin from Fudan University said that any warming of China-India ties at the summit is likely to be cautious and conditional, shaped by competing strategic alignments along with New Delhi’s reluctance to embrace an overtly anti-Western stance.

SHOWCASE OF SOLIDARITY AND CHINESE LEADERSHIP

The SCO has often projected unity through carefully worded declarations while papering over differences among members. Analysts say this year will be no exception.

At a media briefing on Aug 22, Chinese Assistant Foreign Minister Liu Bin said SCO leaders are expected to adopt a 10-year development strategy and issue joint statements marking the 80th anniversaries of the end of World War II and the founding of the UN.

They will also sign agreements to strengthen cooperation in security, the economy, and people-to-people exchanges, while setting the long-term direction of the bloc’s development, Liu added.

But analysts say tangible progress will be difficult to achieve, given the bloc’s inherent contradictions - bringing together rivals such as India and Pakistan, as well as uneasy partners like China and India.

Expansion has only deepened this complexity, with a total of 26 countries now involved as members, observers or dialogue partners.

“Any truly substantive document … (is) not too easy to pass,” said Lin. “What usually emerges is a very general, broad, and bland consensus text without clear focus,” he added.

“If anything, the SCO has held numerous meetings at different levels over the years, but these have often produced limited tangible outcomes. That in itself reflects the challenges the organisation faces in demonstrating its effectiveness.”

Even so, Lin believes the bloc’s differences are not insurmountable. “Disagreements exist, but they can be managed through consultation and bargaining,” he said.

Reyes from HKU said the SCO remains “hard to describe as a coherent organisation”. He noted that since the Ukraine war erupted in early 2022, the bloc has reduced the profile of its joint military drills.

“That’s probably on purpose, because Russia, which is at war with Ukraine, is a member. Beijing is mindful of being seen as aligning with Russia militarily at this point,” he said, adding that the group should not be mistaken for a formal alliance like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

The value of the SCO lies in its optics and inclusivity instead, Reyes said.

“China is creating alternatives, a looser world order, where it’s really about the networking and mutual interaction,” he said, adding that this breadth allows Beijing to present the SCO as a Global South platform, even if its practical impact is limited.

The Global South broadly refers to developing countries that are poorer, have higher levels of income inequality and lower life expectancy.

Yet Beijing’s ambitions may not be easy to realise, especially as the SCO continues to expand.

Additional membership may increase the number of issues in dispute, cautioned Ping from Bond University.

“(It may also) dilute the organisation’s momentum, and bring into question the usefulness of regionalism.”

Beyond the optics, Beijing is pushing for the SCO to broaden its agenda, signalling a desire to shift the focus from security to one that also encompasses economic cooperation, technological innovation and people-to-people exchanges.

According to Chinese officials, the summit agenda will cover infrastructure connectivity, green energy, digital economy initiatives, financial cooperation - including discussion of an SCO Development Bank - as well as artificial intelligence, public health, scholarships and cultural exchanges.

“A strategic pivot from security-centric cooperation to comprehensive regional governance would signal the SCO’s evolution into a platform for development and innovation, with China as the leader,” said Ping.

But delivering on these ambitions will be far more complicated than coordinating security.

“They involve many more actors, beyond the security providers such as military and police, and require opportunity cost, and deference to a China model,” said Ping.

Still, even symbolic outcomes serve a purpose for Beijing, he added.

“The summit reinforces the CCP’s (China’s Communist Party) global narrative of peaceful development and shared prosperity, and its domestic one of rebuilding the Chinese nation.”