Few Singaporeans turn to voluntary mediation despite its success

Less than a third of the cases filed at the Community Mediation Centre moved forward because one side refused to participate.

Mr Thirunal Karasu (left), an executive master mediator at the Community Mediation Centre, in a re-enactment of a mediation session.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Flare-ups between neighbours can be hard to resolve. Yet, despite having free access to mediation, which has been effective in mending ties, many Singaporeans still hesitate to take that step.

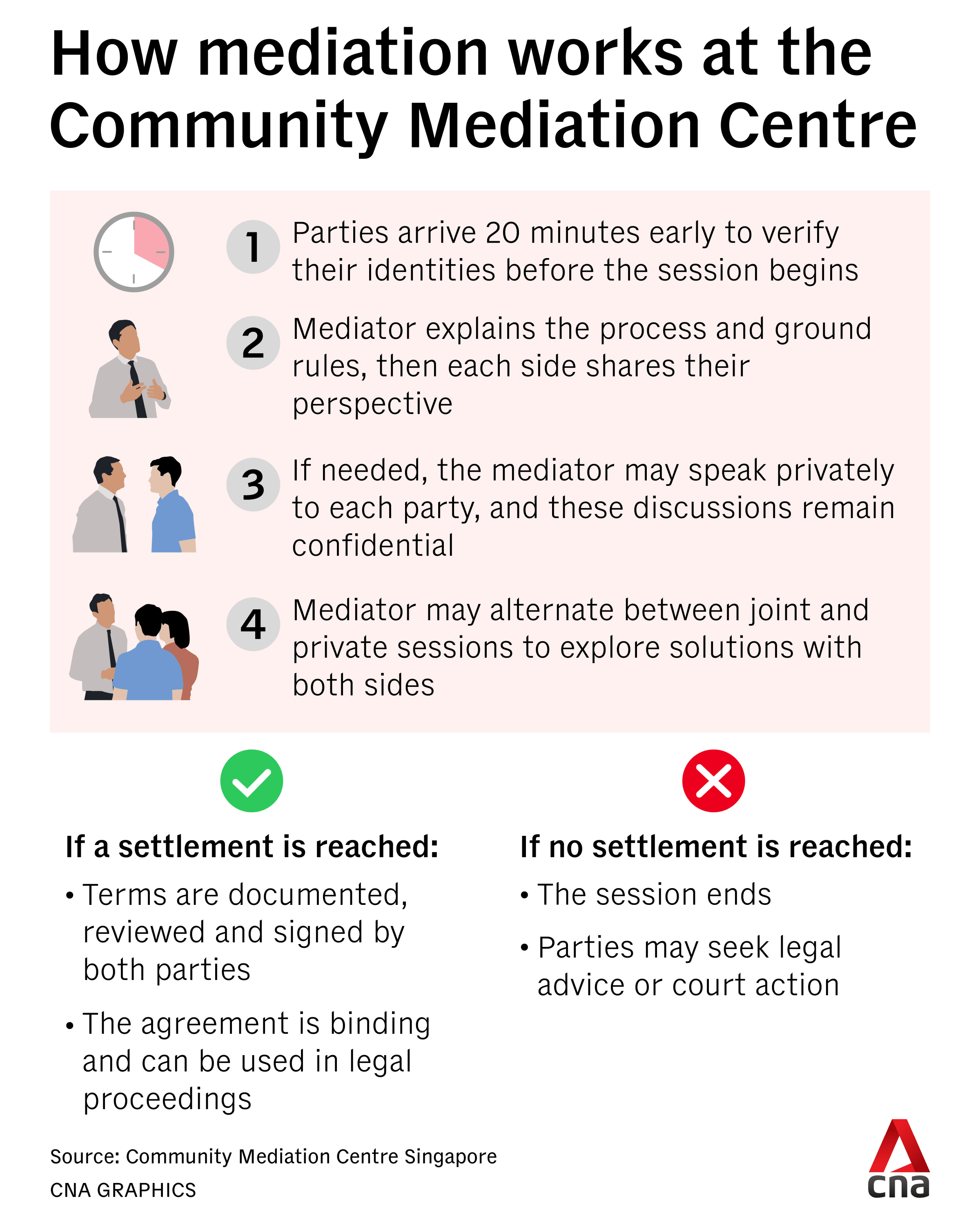

At the Community Mediation Centre (CMC), trained volunteer mediators guide residents in talking through their frustrations, before anger boils over. The goal is not to decide who is right, but to give both sides a fair chance to resolve their disputes early and arrive at a workable solution.

“It's not like going to court. Coming to mediation is very different,” said Mr Thirunal Karasu, an executive master mediator at the CMC, a centre under the Ministry of Law (MinLaw).

“It is a place for us to sit down and discuss our issues. Nobody is going to give instructions,” added Mr Thirunal, who has helped resolve disputes for nearly three decades.

He is part of a growing pool of about 170 volunteer mediators islandwide in locations like community clubs and police posts.

During mediation, parties may choose to reach a settlement agreement. Once signed, it becomes binding.

A QUIET SUCCESS, BUT BARRIERS REMAIN

Today, about 80 per cent of voluntary mediation cases handled by the CMC are successfully settled.

“Even if they don't (reach) a settlement, when they are walking out (of mediation), they are better neighbours. That is an achievement,” said Mr Thirunal, who stressed that mediators only play a facilitative role in the process.

The bulk of neighbourly disputes in Singapore stems from noise.

Overall, the average monthly volume of noise disputes between neighbours in the first half of 2025 has held steady at 2,500, the Ministry of National Development and MinLaw said in September.

However, many parties involved in disputes are unwilling to attempt mediation, despite its track record.

Less than 30 per cent of the total cases registered at the CMC proceed to mediation because one party did not wish to participate, the authorities added.

A major barrier, community mediators said, is a lack of awareness.

Many residents are still unaware that mediation is free of charge and what is discussed is kept confidential.

To encourage participation, CMC staff personally reach out to invite respondents and, where needed, enlist help from grassroots leaders and community partners such as the Housing and Development Board (HDB) or the police, said Mr Thirunal.

“If they still refuse to come, there's nothing much we can do. But the applicant can approach the community and grassroots leaders in his vicinity who know his neighbour and persuade them to come for mediation,” he added.

Concepts of “face” and a sense of being “right” can also make some neighbours resistant to compromise.

To address this, the CMC and grassroots organisations conduct outreach and training efforts, in hopes of normalising mediation as a first resort rather than a last.

GRASSROOTS THE FIRST LINE OF DEFENCE

But before neighbours go to the CMC, there is a growing first line of defence in the heartlands - trained grassroots leaders.

One of them is Mr Andy Lau, who runs a mediation task force in Yio Chu Kang. He has seen its numbers grow from nine volunteers when it first started in 2022 to 24 now.

The veteran grassroots leader has handled everything from hoarding and noise disputes to complex situations involving vulnerable residents.

In one instance, a resident who had just undergone surgery and needed rest, complained about noise from the unit above - unaware that the child upstairs was autistic and had issues controlling his emotions, Mr Lau recounted.

After both sides met to talk, understanding and empathy grew, he said. The unit upstairs added floor mats to absorb the noise, resolving the issue.

Mr Lau added that early communication is key, rather than waiting for the situation to escalate, or worse, turn violent.

“Sometimes they don’t even remember when the problem started. It’s an iceberg. The noise problem is just the tip of it,” he said.

“Underneath it is a lot of layers, where it started many, many years back, and they didn't speak to each other, and it starts to accumulate.”

Often during mediation, disputing parties arrive at a solution on their own, said Mr Thirunal.

“What we need to do is put them at the same table and make them talk about it.”