Uneven terrain, obstructed paths: This is how wheelchair users navigate public pavements in Singapore

Amid the push for more inclusivity in Singapore's transport network, how accessible are pavements for wheelchair users now? CNA accompanies two on their regular route around their neighbourhoods.

Mr Shalom Lim and his caregiver have to walk on the road in his estate, as the pavements are often obstructed. (Photo: CNA/Grace Yeoh)

SINGAPORE: The landed homes at Guan Soon Avenue in Simei are like any other.

The pavements, already narrow, are obstructed by rubbish bins and potted plants. An occasional pile of cardboard boxes overflows from the grass patch to the walking path. Vehicles parked outside the houses often occupy at least half the lane on the two-way street.

All this poses little issue for an able-bodied pedestrian, who may be able to squeeze through tight spots or skirt around an obstacle.

But the same cannot be said for Mr Shalom Lim, a resident living in the area – and a wheelchair user since he was six.

The 27-year-old has Duchenne muscular dystrophy – a genetic disorder characterised by the progressive loss of muscle – and gets around on a motorised wheelchair. An attached ventilator caters to his restrictive lung disease, which is the result of respiratory muscle weakness.

A rubbish bin in the middle of the pavement, for instance, means he needs to travel on the road instead alongside other vehicles. Alternatively, his caregiver helps to move the bin aside.

“Pavements are not very linear, so I have to go diagonally in and out of it. I usually have to go onto the main road itself,” added Mr Lim, whose frustration has been echoed by netizens in online forums.

“And when it comes to landed property, the parking rules are not very rigid. HDB estates are more clear-cut; landed estates are first-come-first-serve.”

Mr Lim recalled an instance when inconsiderate parking hindered him from accessing a path behind a row of landed homes that he usually takes to Eastpoint Mall, so he had to make a detour.

“From my experience, (getting around has) been smooth sailing for the most part, except for getting (to Eastpoint Mall). I need to go through a cul-de-sac. Sometimes there are cars parked there obstructing my path. It doesn’t happen often, but it has been a nasty occurrence,” he said.

LACK OF ACCESSIBILITY INFORMATION

Mr Lim, who works as a community partnerships executive at K9Assistance, admitted he ventures out “more than most people with my condition” because he has a family car that is designed for his wheelchair.

He doesn’t take public transport as it is “too stressful and triggering”. The gap between the platform or pavement and the vehicle also “frightens” him.

Moreover, his housing estate poses “not so much of a concern” as there are no steps on his regular routes.

But many other wheelchair users may not be as fortunate. They face the key challenge of “a general lack of accessibility information”, making it difficult for them to plan their trip ahead of time, said Mr Alvin Tan, assistant director of independent living and caregiver support at SG Enable.

“Accessibility information could refer to the gradient of the path, the presence or absence of ramps and even the presence of trees with exposed roots along a route. Real-time road conditions such as roadworks, damaged pavements and shifted obstacles also affect wheelchair users, as they make a route temporarily inaccessible,” he told CNA.

“While non-wheelchair users can easily walk over or around obstacles, wheelchair users have more difficulty with these, and barrier-free accessible routes are essential for them.”

Needing to detour or find alternative routes is “time and energy-consuming”. And for motorised wheelchair users, their wheelchairs could run out of battery power before reaching their destination, added Mr Tan.

In wet weather, things can get even trickier as not all sheltered routes are accessible. Neither umbrellas nor ponchos offer full protection, he highlighted.

Slippery road surfaces are difficult for wheelchair users to navigate, and motorised wheelchair users could be subject to “rainwater seepage through the battery compartment of the wheelchair, causing costly repairs”.

These concerns underpin a collaboration announced last month between the Singapore Land Authority and SG Enable – Singapore’s focal agency for disability and inclusion – that looks to map out barrier-free routes for wheelchair users for its digital resource OneMap.

The collaboration comes amid a push for better accessibility all around, with the Land Transport Authority having announced its "Friendly Streets" initiative in March, in a bid to transform neighbourhoods into “more pleasant” public spaces that are safer for pedestrians.

Mr Lim, whose caregiver accompanies him everywhere he goes, currently turns to a similar navigation app, SmartBFA, to recce the route before visiting a new place.

The app, which is supported by SG Enable, uses “crowdsourced path accessibility and obstacle data” to recommend faster and easier routes for wheelchair users.

Even so, he prefers to stick to familiar spots: Eastpoint Mall and Changi City Point. He knows the route to these locations, including the barriers, slopes and other obstacles he will need to pass.

Yet, as Mr Lim demonstrated on a sunny weekday afternoon, predictability does not always mean accessibility.

NAVIGATING BOLLARDS, SLOPES, OBSTACLES

For a start, Mr Lim’s regular route from his home to Eastpoint Mall, where he met CNA, is not fully sheltered. He takes the same route back home.

It takes him up and down slopes along the Simei park connector. One is steeper than the other, requiring him to “navigate slower than usual”. But both are challenging – he feels apprehension when approaching the slope down, while uphill is “more tiring”, he said.

A row of bollards separates the park connector from the adjacent road leading up to the landed houses. As Mr Lim approached the bollards, he slowed down, ensuring he was positioned at a suitable angle to turn his wheelchair, then inched between the bollards over a covered drain.

Once on the road, he picked up his pace, albeit ever so slightly. His caregiver followed closely behind, ready to lend a hand whenever he needed a break.

The residential road was mostly quiet on the weekday afternoon, save for an occasional oncoming vehicle. It meant Mr Lim and his caregiver could use the road to avoid the trash bins obstructing the pavement in front of the houses.

Due to Mr Lim’s deteriorating muscles, he uses a mini joystick to navigate his wheelchair as he doesn’t have the strength for a standard joystick.

But the mini joystick is “very sensitive”, and a sudden jerk can cause it to “go out of control”, he said.

Any small movement can also alter the position of his arm, and he doesn't have the strength to move it back in place. This happens often, especially since the ground is not always even, so he has to frequently stop to allow his caregiver to adjust his arm.

“My preferred route would be one that has no humps or uneven terrain. (My wheelchair is) good at navigating indoor or tight spaces like offices, including doing three-point turns. But not for outside use,” he explained.

But his route to Eastpoint Mall is not free from challenges even when he takes his family car. He usually alights at the nearby Housing Board car park, then follows a sheltered walkway leading to the mall.

At the car park, Mr Lim believes the barriers were put up at the alighting point to “prevent cars from crashing through” to the sheltered walkway. But he pointed out that these are “unfriendly to wheelchair users”.

“Luckily I’m able to squeeze through. But I have a lot of equipment; if anything happens, it can be disastrous,” he added.

SG Enable’s Mr Tan highlighted that while public pavements should be designed in a way that caters to the different needs of various members of the public, it is important to balance these differing needs in cases where “conflicts could arise”.

“For example, making tactile markings widely available on public pavements would help people with visual impairment or low vision on their travels, but it could pose a problem for wheelchair users,” he said.

“In such cases, we need to respect these differing needs and choose a feasible solution that benefits most where possible.”

However, pavements at newer HDB estates are designed to be accessible, such as made wider and with even surfaces, he added.

Existing designs that pose challenges for wheelchair users

Senior occupational therapist Sharmaine Chan told CNA about some designs that may challenge wheelchair users:

- Steep street gradients or side slopes result in wheelchair users being unable to manoeuvre their wheelchair safely

- Ramps that are “too long” require wheelchair users to have the "physical endurance" to navigate a long distance up or down the slope

- Ramps or slopes that are tiled and/or unsheltered become slippery in wet weather conditions, which increases risk of wheelchair skidding

- Down slopes leading to zebra crossings make it difficult for wheelchair users to stop safely before the zebra crossing before crossing the road

- Steps or kerbs, especially in areas like parks, make it difficult for wheelchair users to enjoy the park with ease

- A lack of signs leading to accessible walkways results in wheelchair users spending extra time trying to find an accessible route. At the same time, accessible routes can sometimes require wheelchair users to take a longer route, such as by going around the building

- Paths can sometimes be too narrow, limiting wheelchair users from navigating safely in areas like Geylang and Chinatown where restaurants have outdoor seating or shops have large decorative pieces placed outside. This can be made more challenging with temporary barriers, such as exposed cabling, as well as bollards and barricades aimed to deter reckless cyclists and other motorised personal mobility aid users

SMOOTH, ACCESSIBLE PAVEMENTS

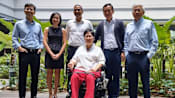

When CNA met another wheelchair user, Ms Sherry Toh, at Rivervale in Sengkang to observe the difference in accessibility within an HDB estate, she acknowledged that her block was “quite accessible”.

The 25-year-old freelance writer has spinal muscular atrophy type 2 – a genetic neuromuscular disorder affecting the nerve cells that control voluntary muscles – and has lived in Rivervale for almost two decades.

Ms Toh, whose condition means she can’t operate her manual wheelchair, goes everywhere with her caregiver. The nearest bus stop and LRT station, as well as Rivervale Plaza, are connected to her block by sheltered walkways.

The pavements are “quite smooth and accessible”, albeit “a bit narrow in some places”, she said.

“For example, if there are trees, it makes it harder to navigate the wheelchair sometimes. When the pathway is narrow, you have to watch out for where the pavement ends and where the dirt or tree’s roots begin.”

And while wet weather conditions can affect her caregiver as she has to shelter Ms Toh and look out for slippery slopes, the streetlamps and cars help to illuminate the pathways at night in her estate, she added.

Meanwhile, the pavements leading to the car park located on the third and fifth floor of an adjacent block that links to Ms Toh’s are wide and smooth. Save for a mini hump in the pavement, Ms Toh’s caregiver is able to push her along with ease.

Ms Toh acknowledged that manual wheelchair users who manoeuvre themselves around may have it harder.

“If there’s no smooth pathway, then it’s very bumpy and not very pleasant to drive through. You get a lot of dirt on tyres if the path isn’t smooth enough,” she said.

Sometimes, to avoid the hassle of alighting at the car park, she uses the loading bay area on the ground floor. But there is only one ramp at the front of her block – and it is occasionally obstructed by vehicles. In such cases, she relies on her caregiver, parents or brother to lift her wheelchair onto or off the kerb.

“Whenever there is (a feature) that seems like an afterthought, it applies to ramps. And sometimes, ramps are so far away from the actual pathway,” she added.

Ms Chan, the occupational therapist who spoke to CNA, noted that while there are “undoubtedly a lot more” ramps built, they are not actually accessible, because they are either too steep or too narrow.

“Accessibility features should be a part of the development plan from the get-go and (involve) consultation with different community groups, including those with disabilities, to understand their needs,” she said.

Wheelchair users, as well as the general public, should also be informed of who they can contact should they come across any obstructions or barriers that could limit wheelchair users from getting around safely, such as cracks or uneven ground surfaces, barriers or bollards, she added.

And where possible, they can "assist with shifting temporary obstructions in pathways", such as rubbish bins and bicycles.

Ms Toh's mother has approached drivers who obstruct the loading bay to ask them to move. But the family has not appealed to the authorities, such as their Member of Parliament.

The inconsiderate behaviour, she believes, is ultimately “an individual’s choice”.