IN FOCUS: Why Southeast Asia’s service providers remain stuck at home, and how ASEAN can help

With Trump 2.0 reshaping global trade, boosting trade in services could offer ASEAN a growth path – but only if governments harmonise rules and tackle protectionism, experts and companies say.

Cultural differences, different regulatory frameworks, protectionism and other issues are hampering Southeast Asian countries from boosting trade in services. (Illustration: CNA/Rafa Estrada)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JAKARTA/KUALA LUMPUR: In a cramped office on the second floor of a weathered building in Bandung, Indonesia, a dozen animators sit shoulder-to-shoulder, eyes glued to the screen, as they bring characters to life frame by painstaking frame.

The walls of the six-by-six metre office are adorned with paintings of characters developed by the animation studio, Ayena, as well as the many national, regional and international awards it has collected since its founding in 2015.

Despite the accolades and an impressive portfolio that includes some animation and rendering work for the 2025 Indonesian animation hit Jumbo, Ayena has struggled to land international clients on its own.

“Most of the stuff we are working on are subcontract works from other companies overseas,” its chief executive Robby Ul Pratama told CNA.

Because being a subcontractor means earning lower fees and less recognition for its animators, the studio has been trying to cut out middlemen and secure clients on its own – with little success.

“The excuses we got so far: ‘There is too much red tape in Indonesia’, ‘there is not a lot of support or incentives for the animation industry in Indonesia’ and ‘Indonesia’s intellectual property protection is weak’,” Robby said.

Some of these projects were later awarded to studios in Eastern Europe, Latin America and other Southeast Asian countries. “The funny thing is, sometimes these studios hire us as subcontractors to do the same projects,” Robby said.

Over in Singapore, energy services company Measurement and Verification (MnV) has also struggled to find clients after expanding to Malaysia in 2018.

The company was trying to prove to investors its business model was scalable and was convinced that its reputation for improving energy efficiency in some of Singapore’s most prestigious shopping malls and hotels would translate to instant success across the Causeway.

But the challenges were many, said MnV managing director Steven Kang. The lack of connections, different business cultures and the absence of regulatory requirements for Malaysian building owners to go green meant the company was hardly getting any clients.

“(The reason) why many energy services companies succeed in Singapore (is) because the government is pushing energy efficiency very strongly. If your building consumes too much energy, by law, you have to do something about it,” Kang told CNA.

“In Malaysia, they encourage but they don't make it mandatory.”

MnV Malaysia survived because several of its Singaporean clients expanded their operations into Malaysia, bringing with them the same energy efficiency standards adopted at home.

Even then, operational headaches such as hiring local workers and the deployment of employees from Singapore to Malaysia proved as daunting as the securing of contracts.

These experiences underscore the persistent challenges standing in the way of expanding Southeast Asia’s trade in services, which various Association for Southeast Asian Nation (ASEAN) leaders have called for in the wake of punishing goods tariffs of 10 to 40 per cent imposed by the United States.

ASEAN leaders see deeper cooperation in services as a way to keep their economies resilient.

"For example, we said that the ASEAN free trade area is virtually tariff-free, which is very good. But why can’t we be 100 per cent tariff-free?" Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong said at the ASEAN Summit leaders’ retreat on May 26.

ASEAN tariffs have been eliminated for 98.6 per cent of products under the ASEAN Trade in Goods Agreement (ATIGA).

“Beyond trading in goods, we should also accelerate trading in services. This is also an important part of the economy, and we can do more to facilitate this,” Wong said.

At the end of the retreat, ASEAN leaders agreed they should work to enhance the competitiveness of the region’s services sectors and facilitate more trade in services.

But even in countries such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, where services already account for over half of gross domestic product (GDP), anecdotal evidence and observer accounts suggest few companies manage to navigate the maze of cultural, regulatory and structural hurdles to expand beyond their borders within the region.

Which is why trade in services has been sluggish within Southeast Asia, even as the sector brims with untapped potential, according to official data.

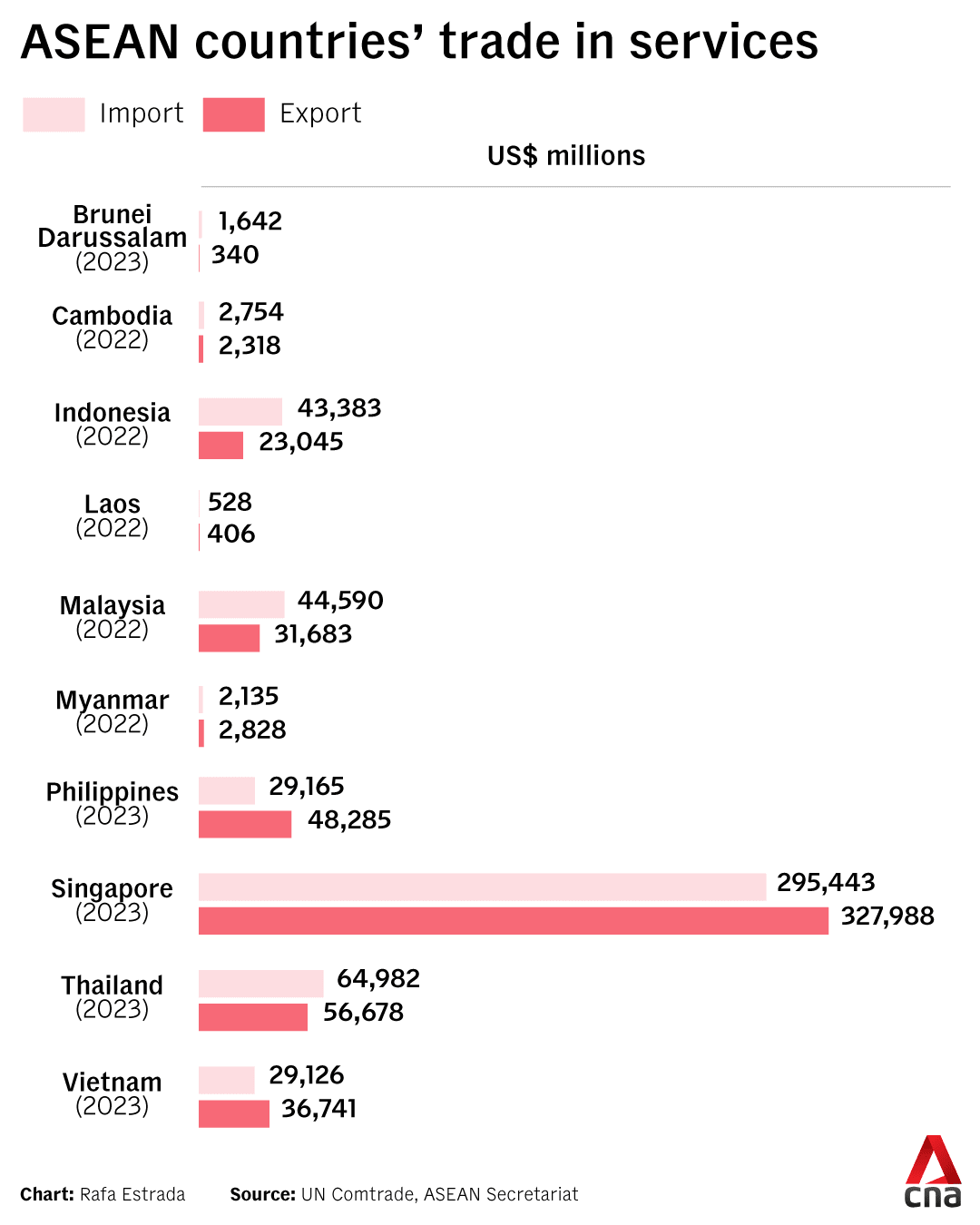

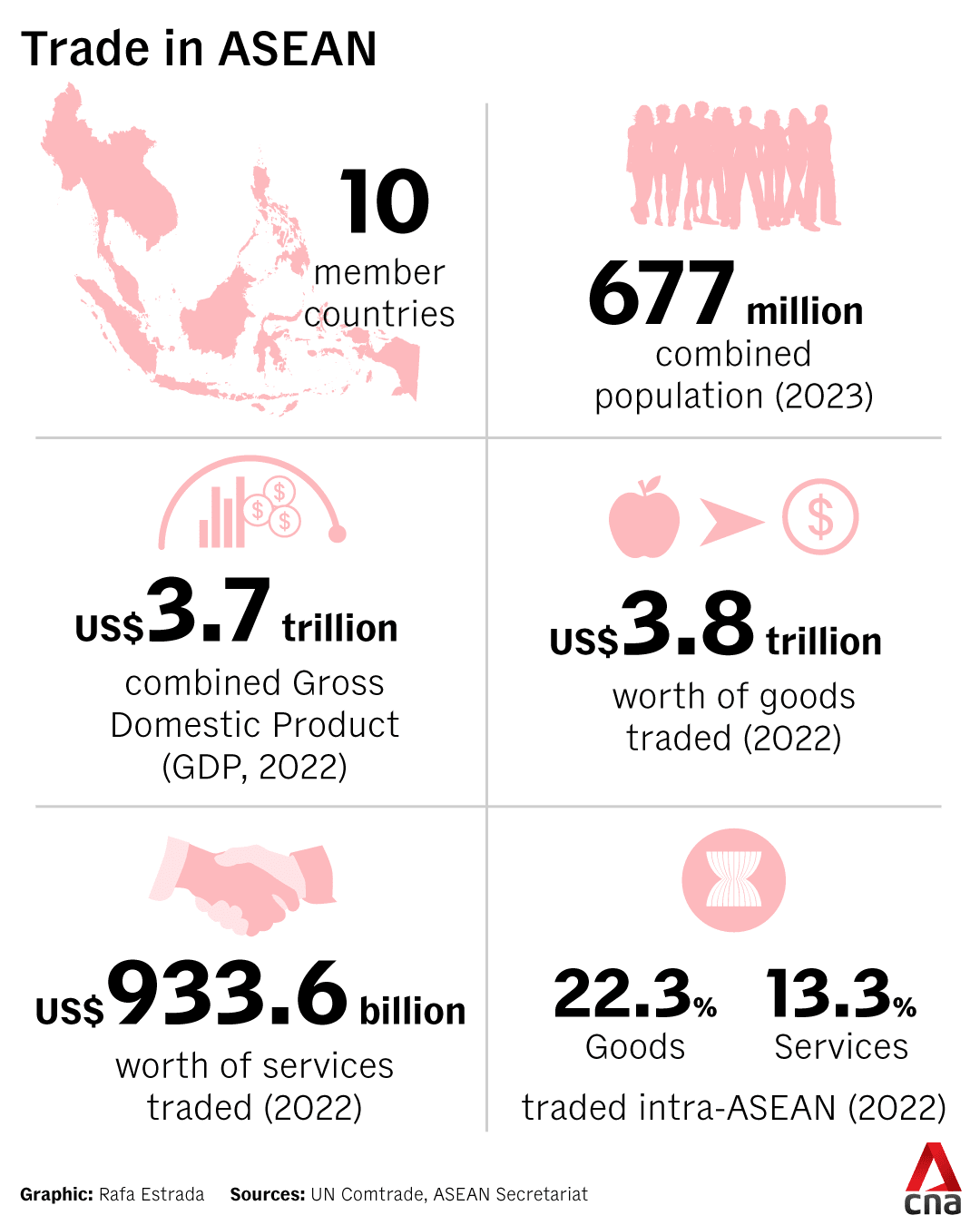

ASEAN’s total trade in services was US$933.6 billion in 2022, of which only 13.3 per cent was intra-ASEAN, according to statistics published by the ASEAN Secretariat.

Transport, travel, financial and telecommunications were among the top categories of services traded. Singapore was the largest market for services trade in ASEAN by far, accounting for 58.9 per cent of the region’s total.

In contrast, ASEAN’s total trade in goods was US$3.847 trillion in 2022, 22.3 per cent of which was intra-ASEAN.

According to the United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade), only the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam recorded trade surpluses in services in 2023.

The other seven ASEAN members imported more services than they exported, often from far flung corners of the world. These imported services ranged from education, entertainment and healthcare to internet technology services and financial consultancy.

The benefits of boosting trade in services within ASEAN is a no-brainer. “Apart from the fact that tariffs are not applied to services, opening up the sector offers a huge potential for the region,” said a spokesperson for HSBC Global Investment Research.

But the ambition will have to be matched by real-life action and commitment from ASEAN members, said experts.

WHAT’S HOLDING ASEAN BACK?

There is much to be done to remove deep-rooted barriers such as cultural differences that affect how business is done, regulatory frameworks that vary country by country, and issues such as uneven infrastructure, legal systems and workforce skills, the experts said.

Regulatory fragmentation remains the biggest hurdle, with each country in the region having its own tax regimes, business policies, ownership rules and data management regulations, they said.

“Each of the ASEAN member states operates very differently with their own sets of regulatory frameworks … It’s not easy for foreign businesses to understand and navigate,” said Winnie Seow, international markets lead at corporate services consultancy Hawksford.

There is also a lack of recognition among some ASEAN countries of professional qualifications and corporate certifications issued overseas.

“Sometimes, clients from Singapore or Thailand want to see whether we are certified to do certain tasks or if our company meets certain data security requirements and standards,” Jansen Gunawan, a Jakarta-based freelance computer engineer, told CNA.

Jansen said there have been many occasions where these clients did not accept certificates issued by an Indonesian firm or organisation. Sometimes, they even refused to accept those issued by the Jakarta branch of a well-known international tech company.

“In the beginning, I tried to argue that my certificates were as good as those issued elsewhere. But eventually I thought, ‘Why bother? Why work with this person when the trust is just not there?’,” he said.

Even if service providers manage to overcome these hurdles and secure contracts from overseas clients, they still need to navigate differences in business culture, consumer behaviour, language barriers and bureaucratic red tape.

Kang of MnV said his Malaysian operations had to run without a leader for weeks because of an immigration procedure.

The company appointed as its Malaysia general manager (GM) a staff member who was a Myanmar national with Singapore permanent resident status. The process of getting a Malaysian work visa for the employee was “quite challenging” and “not clear”, Kang said.

The visa was eventually approved after the company enlisted the help of a consultant. After the approval, the employee was told that he was not allowed to enter Malaysia while waiting two to three weeks for the visa to be issued.

“This affected our operations. For a GM (to be unable to) enter Malaysia for about three weeks, it is quite disruptive,” Kang said.

Cross-border projects like the Pan Asian railway to connect China’s Kunming with several Southeast Asian cities or the ASEAN Power Grid initiative to connect the electricity networks of most member countries could serve as a testing ground to see how the bloc can address these challenges, said Seow of Hawksford.

“If we can have standardisation ... for all cross-border ASEAN projects and have member countries involved to agree to a standardised framework which all will follow, I think that will make the provision of services a lot easier for these types of projects,” she said.

PROTECTIONISM ABOUNDS

Over the years, ASEAN has signed multiple agreements aimed at liberalising services trade.

They range from the 1995 ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS) – which aims to open markets in areas like finance, telecommunications and professional services – to the more recent ASEAN Trade in Services Agreement (ATISA). Signed in 2020, ATISA built on AFAS by creating a more modern framework and providing a clearer legal basis for services liberalisation across the region.

On paper, these commitments promise freer movement of capital, skills, and cross-border service flows. In practice, however, they are often non-binding, unevenly implemented or selectively enforced.

“On the ground, services continue to be protected on an individual-country basis, either by restricting foreign entry or ownership, putting up barriers to competition, or imposing restrictions on specific jobs,” said a HSBC Global Investment Research spokesperson.

Thailand, for example, reserves occupations such as hairdressing and woodworking exclusively for Thai nationals while Indonesia maintains equity limits and nationality requirements in sectors like insurance, the spokesperson said.

And market liberalisation often collides with the interests of entrenched local players with clout and influence in their respective countries.

“There is not enough dynamism in the new service startups,” said Pavida Pananond, professor of international business at Bangkok’s Thammasat University.

“Domestic conglomerate groups exert strong control across many sectors, from manufacturing to services. That restricts new players and gives undue advantage to established groups.”

Pavida noted how some countries like Thailand lag in creating a level playing field for new players. “Take digital banking. The (Thai) government prefers established banks expanding into digital, rather than encouraging newcomers who could disrupt traditional banking,” she said.

This protectionist environment makes it exceptionally hard for companies to scale across borders.

“Building a startup in one ASEAN country is already challenging enough. Expanding to another more than doubles that challenge,” Jianggan Li, the CEO of Singapore-based consultancy Momentum Works, told CNA.

“Navigating different regulatory, legal and business environments requires not only technical expertise but also strong organisational capabilities. That’s why in most countries (in Southeast Asia), local champions dominate.”

These challenges are compounded by the fact that languages, customs and consumer profiles sometimes differ greatly from one Southeast Asian country to another.

“It is easier (for a service company) to expand into markets with similar consumer behaviours, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, or in sectors where consumer behaviour transcends cultural boundaries, like live-streaming or (popular) toys,” said Helen Wong, managing partner of AC Ventures, one of Indonesia’s biggest investment firms.

Beyond these niches, cross-border expansion is rare as companies focus on their local markets.

Those with regional-growth ambition would have to deal with different purchasing power, consumer behaviour and cultural sensitivities across ASEAN. Which is why some companies choose to merge or acquire similar businesses in another country as a way to enter an unfamiliar market.

However, not many companies are willing to go down this path, AC Ventures' Wong noted, “due to the complexity of post-merger integration, as well as valuation mismatches between companies.”

BRIDGING THE GAP

The May ASEAN summit concluded with calls for the 10 member countries to expedite implementation and execution of trade-related agreements like ATISA, AFAS and a host of other treaties.

"My officials found that there are 24 economic agreements that have still not been implemented, even though they have been agreed upon. Some were agreed as early as 2015," Singapore prime minister Wong said during the summit.

Due to the non-binding nature of these agreements, international relations expert Teuku Rezasyah of Indonesia’s Padjadjaran University said it is no surprise that many of them are not adopted by the countries that signed them.

“During summits, when they issue joint statements or sign agreements, ASEAN countries appear together. But when the time comes to implement them, to each their own,” he said.

Not all member countries feel that they stand to benefit from a liberalised service market, experts noted.

“Some countries see liberalisation as a threat rather than something which will save their economies from (the US) tariff war,” Teuku said.

Laos, for example, has been hit with a 40 per cent tariff on its goods by the Trump administration, the highest in the region. The country enjoyed a US$700 million trade surplus with the US last year due to its export of eyewear, broadcasting equipment and video displays.

But to mitigate the effects of the tariff, experts reckon the country may be more inclined to look to other markets to export its goods rather than ramping up its fledgling service sector.

Laos exported US$406.1 million and imported US$528.3 million in services in 2022, according to the ASEAN Secretariat. Its services trade was the smallest among the ASEAN states, and only Brunei had a lower value of services exported than Laos.

Pavida of Thammasat University said this uneven landscape is the reason why support for liberalisation might be limited to countries that are already strong in services, like Singapore and Malaysia. “More should be done in implementing what has already been agreed,” she said.

LESSONS FROM EUROPE?

Experts said for years, this asymmetry between countries that see cross-border services as a necessity and those content to focus inward has been holding ASEAN back.

But with member countries seeing their manufacturing sectors potentially shrinking due to US tariffs, there is now greater incentive to work together and make a truly regional service economy a reality.

International relations expert Teuku said other blocs have already shown it can be done, albeit through a long and politically charged process with many stumbling blocks and lessons learned along the way.

The European Union, for example, not only managed to eliminate tariffs and quotas but also harmonised regulations and established mutual recognition of professional qualifications.

Teuku noted the bloc also established institutions to enforce the rules like the European Court of Justice to settle disputes and the European Commission to monitor compliance and push reforms even when governments resist.

“ASEAN, with its consensus-based decision-making process, certainly cannot emulate the EU’s success,” he said. “But there are elements, like standardising regulations and recognising each other’s standards and certifications, which ASEAN can adopt.”

The stakes are high. Other regions are already borrowing from the EU playbook.

Latin American economic bloc Mercosur and the post-Soviet grouping Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) are exploring ways to integrate services more deeply, threatening to outpace ASEAN and draw away investment.

But industry players believe the fixes are within reach.

“Greater regulatory harmonisation is crucial to transform ASEAN into a unified market, rather than a collection of disparate ones,” said Wong of AC Ventures.

She also pointed to simplifying licence acquisition, encouraging cross-border projects such as the Johor-Singapore-Batam growth triangle, and even exploring capital market integration – from dual listings to a regional exchange – as steps that would ease expansion.

The service industry itself should not sit still and wait for governments to take action. “Some progress may come from bilateral or multilateral agreements, but much will have to evolve through the market itself,” Li of Momentum Works said.

Already, companies are testing models of integration, said Li.

Singaporean e-commerce platform Shopee, for example, is developing its “Shopee International Platform” to allow merchants in one ASEAN country to sell easily in others. Meanwhile, there have been a number of fintech and logistics firms from different parts of the region forging partnerships to bridge regulatory gaps.

“Services could be the region’s untapped growth engine, a way to insulate against tariff wars and diversify beyond goods,” said Bhima Yudhistira, executive director of Jakarta-based think tank Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS). “But realising that promise will demand something ASEAN has often struggled with: Moving beyond rhetoric to real reform.”

A good starting point is to play to each country’s strengths like tourism and hospitality for Thailand, financial services for Singapore or logistics for archipelagic Indonesia.

“The question now is whether Southeast Asian countries are ready to set aside their differences and get serious about integration,” Bhima said.

Ayena’s Robby certainly hopes so. For too long, he said, talent and ambition have been rarely matched by the opportunity for growth, and the gap between recognition and real support is stark.

“We tried to speak to various ministries about our grievances, but there wasn’t much response,” he said.

“Yet when we won prestigious awards, suddenly officials showed up to take credit saying, ‘This is the SME (small and medium enterprise) studio we helped foster’,” Robby said.

Other countries, he pointed out, offer grants, promote their studios at global expositions and festivals, and champion international certification and protection for their creative industry. These give foreign clients the confidence that intellectual property will be safeguarded and information security maintained.

“If ASEAN can really push Indonesia to do those things,” Robby said, “it would be good for the industry.”