IN FOCUS: Is Prabowo seeking to push Indonesia as a middle power, and why does it matter?

As Southeast Asia’s biggest economy and the world’s biggest Muslim-majority country, Indonesia has the potential to become a credible middle power. Can Prabowo make this happen?

Indonesia's President Prabowo Subianto gestures following the 28th ASEAN-Japan Summit, as part of the 47th ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on Oct 26, 2025. (Photo: REUTERS/Chalinee Thirasupa/Pool)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

JAKARTA: Indonesia has long been guided by a “free and active” foreign policy. But that principle has been taken to an unprecedented level since Prabowo Subianto was inaugurated as the country’s eighth president in October 2024.

Over the past year, the archipelago has aligned itself more closely with members of the economic group BRICS such as China, India and Brazil, while also strengthening ties with Moscow at a time when Russia was becoming increasingly isolated over its invasion of Ukraine.

Almost simultaneously, Jakarta has deepened military cooperation with NATO countries and their allies such as South Korea and Australia and joined the United States-led Board of Peace.

Prabowo has also signalled a willingness to recognise Israel as part of a broader push for peace in the Middle East – a significant departure from the language traditionally used by Indonesian leaders.

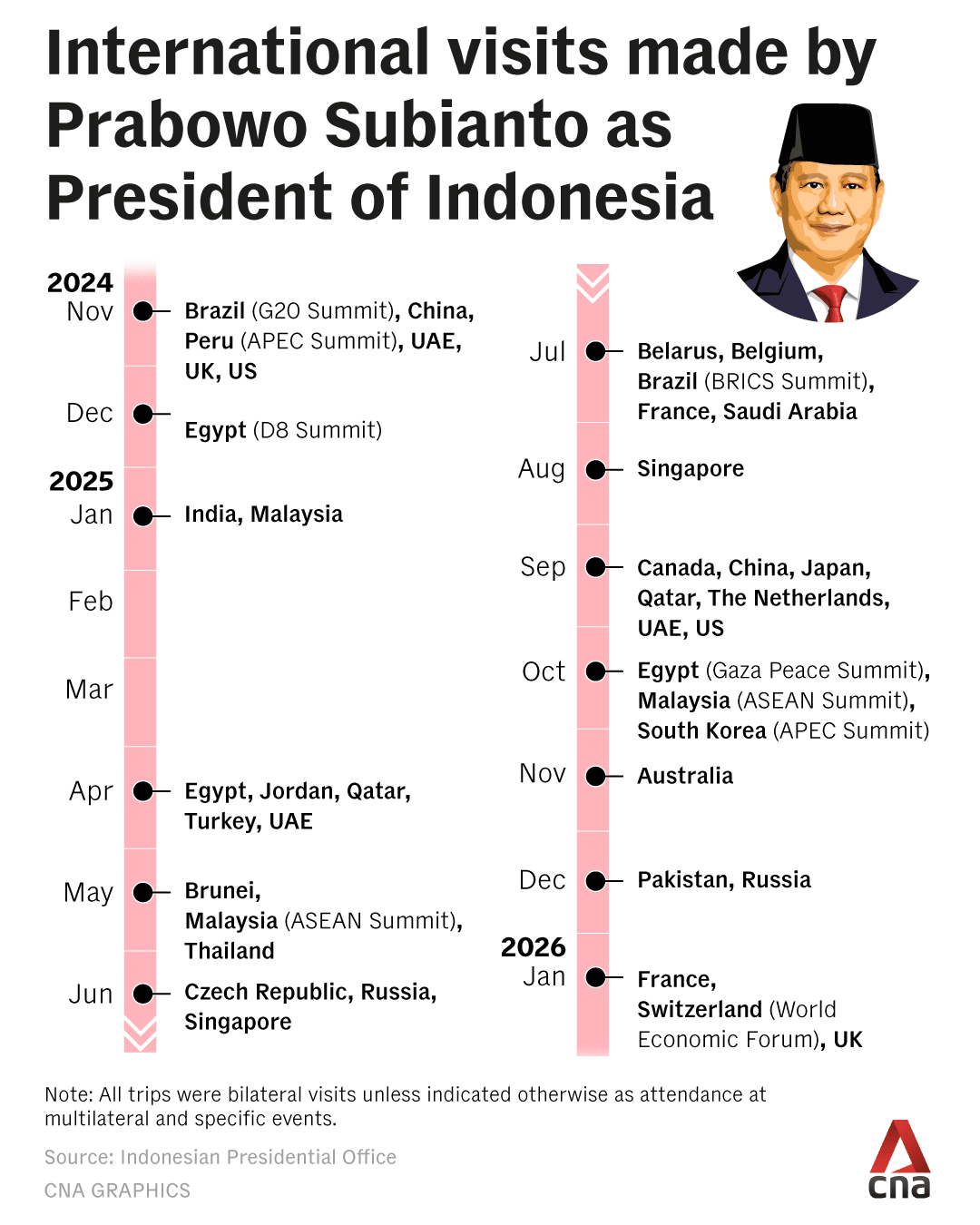

Since assuming office, the 74-year-old retired general has also pursued an intense diplomatic schedule, attending nine international summits and making more than 40 official visits to more than 20 countries, spanning major powers and smaller strategic partners alike.

The numbers far exceed that of his predecessor Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s 16 state visits, or former president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s 10 overseas trips, in their first full years in office.

“Prabowo is currently positioning himself as a qualified middle power – one that is ready to engage directly with the major powers,” said Teuku Rezasyah, an international relations expert from West Java’s Padjadjaran University.

Experts said in today’s increasingly fragmented world – marked by US protectionism, geopolitical and economic rivalry between Washington and Beijing and prolonged conflicts in Europe and the Middle East – Indonesia may have the opportunity to position itself as a bridge-builder, mediator and agenda-setter.

“People like (Prabowo) can take Indonesia’s diplomacy to the next level,” said Hikmahanto Juwana, a professor in international law at University of Indonesia.

But analysts warned that Indonesia’s push for a larger global role may come at a cost, potentially diverting attention from pressing domestic and regional priorities.

BIG POTENTIAL

A middle power is a country that – while not a major power like the US, China or Russia with overwhelming military strength and political or economic clout – is able to punch above its weight through active diplomacy, leadership in multilateral institutions and expertise or credibility in areas aligned with its national strengths.

Australia is a prime example of a middle power, with its active diplomacy regularly shaping security and economic agendas in the Indo-Pacific. Another is Norway, which has established itself as a respected mediator in international conflicts, including in the Middle East, Latin America and several parts of Asia.

Indonesia has many of the structural and normative attributes of a middle power, experts noted.

It is Southeast Asia’s largest economy, the world’s most populous Muslim-majority nation, and a key member of major global forums such as the Group of 20 (G20) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

These factors help explain why Indonesia — despite not being a member — has regularly been invited to attend Arab League and Group of Seven (G7) summits.

“Indonesia is seen as an attractive maiden being courted by many,” said Hikmahanto.

Indonesia also has a long history in international collaboration, from being a co-founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), to hosting the landmark Asia-Africa Conference in 1955.

It has also maintained a longstanding tradition of not aligning itself with any single major power, allowing Jakarta to engage multiple parties without binding allegiances.

Analysts said that today, Indonesia has an additional factor that could strengthen its middle-power ambitions: Prabowo’s foreign policy philosophy that “one thousand friends are not enough, one enemy is too many”.

“Prabowo also has the confidence to be on the same stage as world leaders, and he has a passion for geopolitics,” said Hikmahanto.

These traits were shared by Indonesia’s founding father Sukarno who turned Indonesia into a diplomatic powerhouse and a leading voice of the developing world, said experts.

“Prabowo is perhaps inspired to emulate Sukarno’s accomplishments, which was transforming Indonesia into a nation full of ideas, credibility and network,” said Rezasyah of Padjadjaran University.

Experts said the opportunity for Indonesia to assume a greater international role is now larger than ever.

They argued the world is increasingly in need of credible middle powers at a time when the US has imposed sweeping tariffs on countries across the globe, withdrawn from key international organisations and treaties and taken steps that risk undermining global stability and the rule of law, such as its posture towards Venezuela and threats to exert control over Greenland.

Indonesia’s own foreign ministry has echoed these concerns.

“We are concerned about the prospect of multilateralism coming under increasing pressure and the growing challenges facing a world built on international cooperation,” said Indonesian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Yvonne Mewengkang at a press briefing on Jan 8.

Indonesia has called for dialogue and expressed “grave concerns” over the use of force following the US capture of Venezuela’s now-ousted leader, Nicolas Maduro, saying in a foreign ministry statement that the actions “risk setting a dangerous precedent in international relations and could undermine regional stability, peace, and the principles of sovereignty and diplomacy”.

In regards to the US’s attempt to control Greenland, Foreign Minister Sugiono said on Jan 23 that Indonesia has chosen to remain neutral but urged all countries to maintain peace and stability.

On both issues, Indonesia did not explicitly mention the US or Trump by name, which Hikmahanto said strengthened Indonesia’s credibility as a potential mediator.

“It is hard to broker dialogue and peace if Indonesia openly condemns certain actors,” he said.

If leveraged effectively, Indonesia’s consistency in maintaining neutrality could position it as a bridge-builder and peace broker in some of the world’s most volatile flashpoints, including ongoing tensions and conflicts in North Africa and the Middle East, the professor said.

But others argued that Prabowo should begin closer to home.

“The most obvious weakness in Indonesian foreign policy today is its abandonment of regional politics,” said Made Supriatma, a visiting fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

He noted that as Indonesia increasingly focuses beyond Southeast Asia, Malaysia has taken on a more prominent role in efforts to address the civil war in Myanmar as well as tensions along the Thailand–Cambodia border.

As the previous ASEAN chair, Malaysia sent representatives, such as its foreign minister, to Myanmar for talks with the junta on the country’s elections and a potential peace plan.

Malaysia also helped broker a short-lived ceasefire between Thailand and Cambodia in July last year.

Indonesia was ASEAN’s chairman in 2023 but then-foreign minister Retno Marsudi continued to push for dialogues and cessation of violence in Myanmar until her term ended in October 2024.

“I believe that if Indonesia demonstrated its leadership as a regional power, major powers would view Indonesia much more seriously than they do now,” Made said.

CHALLENGES ABOUND

With more than 40 official visits, Prabowo is perhaps one of the world’s most well-travelled heads of state in 2025. In January, Prabowo added the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland to his list of summits and Great Britain and France to his list of state visits.

US President Donald Trump, in comparison, visited only 14 countries last year including the ASEAN summit in Kuala Lumpur in October. Many of Trump’s overseas duties were left in the hands of his State Secretary Marco Rubio who visited 28 countries in 2025.

Meanwhile, Chinese president Xi Jinping made eight overseas trips in 2025 while his premier Li Qiang made 12 international visits including to Jakarta in June.

So why has Prabowo decided to personally visit so many countries?

Experts said it signals that Indonesia is serious about fostering relationships with major powers but it also shows Prabowo as a hands-on and centralised leader.

In doing so, he leaves little room for Foreign Minister Sugiono, a career politician with little diplomatic background, to emerge as an independent diplomatic figure, added observers, who said the latter has a tough job of transforming the outcomes of Prabowo’s overseas visits into actionable results.

“Sugiono doesn't seem on the same level as his predecessors. Furthermore, he has never held an executive position and lacks diplomatic experience. It's not surprising that he struggles to lead Indonesian diplomacy,” said Made of Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

In an opinion piece which appeared in Kompas newspaper on Oct 21, around the one-year mark of Prabowo’s presidency, former Indonesian ambassador to Ukraine, Yuddy Chrisnandi, noted that Prabowo’s visits have resulted in many investment pledges worth a total of more than US$112 billion.

But the president, he wrote, still needs experienced diplomats to turn these pledges into realities.

“The president, as the real foreign minister, needs to be supported … by experienced individuals with proven track records in leading diplomatic missions, so they can serve as dynamic counterparts in jointly formulating international diplomatic agendas with the president,” wrote Yuddy, who is also a professor of political science at National University in Jakarta.

Former Indonesian ambassador to the United States, Dino Patti Djalal, said Sugiono appeared to be busier in his other role as secretary general of the Great Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) - a party co-founded and chaired by Prabowo - than leading the country's diplomats and foreign ministry officials.

“The Foreign Ministry is like a Ferrari — full of extraordinarily talented diplomats. But a Ferrari can only perform at its best if it is driven by a skilled and focused driver,” Dino said in an Instagram post on Dec 21.

When asked about the criticisms aired by Yuddy and Dino, foreign ministry spokeswoman Yvonne said: “The ministry of foreign affairs respects these constructive inputs and consistently opens its doors to different points of view.”

Prabowo’s hands-on leadership style and limited consultation with experienced diplomats have at times led the Indonesian president to take positions that deviate from long-held foreign policy stances, experts noted, citing how he has also occasionally made off-the-cuff remarks that caused some confusion and controversy.

After meeting Chinese President Xi Jinping in November 2024, Prabowo said Indonesia and China had agreed to jointly develop the maritime economy in their overlapping areas of the South China Sea.

While Indonesia does not claim any part of the South China Sea, China’s so-called “nine-dash line” overlaps with Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone around the Natuna archipelago in Riau Islands province.

Experts warned Prabowo’s remarks could be interpreted as tacit recognition of China’s expansive claims over the resource-rich waters — claims long contested by several Southeast Asian countries namely the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei.

“Indonesia’s agreement to China’s joint development proposal dismantled a diplomatic position it had upheld for more than 20 years,” said Yohanes Sulaiman, an associate professor at West Java’s Achmad Yani University.

Yohanes noted this was not the first time Beijing had proposed joint development in the Natuna area. Former presidents Yudhoyono and Jokowi had consistently rejected the idea, arguing that accepting it would amount to recognising China’s territorial claims.

Another statement that departed from Indonesia’s traditional position came during Prabowo’s address to the United Nations General Assembly on Sep 23, when he pledged to recognise Israel if it, in turn, recognised Palestinian statehood.

He also said the international community must “recognise and guarantee the safety and security of Israel”, striking a markedly different tone from previous Indonesian leaders, who have long prioritised Palestinians’ right to self-determination over Israel’s security concerns.

Prabowo has also accepted the US’s invitation to join the Board of Peace, an institution originally established to ensure that post-conflict reconstruction in Gaza proceeds effectively.

Trump has reportedly invited around 60 countries, with over 25 having accepted so far, including Israel as well as fellow Southeast Asian nation Vietnam. Meanwhile, France, Norway and Sweden have declined the invitation, while countries such as India, China, Singapore and Russia are still considering their positions.

Some observers argued that Indonesia risks being drawn into a pro-American orbit that prioritises the American president’s agenda.

“It is normal for a country to adjust its diplomatic stance from time to time. But such changes must be backed by clear reasoning and solid arguments,” Yohanes said.

“Those arguments need to be explained to the Indonesian public and the international community. Unfortunately, Prabowo has not done so.”

On Feb 3, Prabowo met with more than 40 Islamic leaders and representatives from Islamic organisations to explain his decision. After the meeting, Indonesian foreign minister Sugiono told reporters that Indonesia may withdraw from the Board of Peace if goals such as advancing Palestinian independence are not met.

On Feb 9, State Secretary Prasetyo Hadi announced that Prabowo had received an invitation to the inaugural Board of Peace leaders’ meeting in the US later this month but cannot confirm whether the Indonesian president will attend the talks.

A BALANCING ACT

With Prabowo travelling so frequently, observers said the former general must also ensure that domestic responsibilities are effectively managed by members of his Cabinet during his overseas trips — and be prepared to delegate or postpone travel when domestic crises demand his full attention.

In September, Prabowo travelled to Beijing to attend the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II after initially cancelling the trip. At the time, Indonesia was still grappling with widespread anti-government protests and riots.

State Secretary Prasetyo said that Prabowo ultimately agreed to honour China’s invitation after making sure that the security situation in Indonesia had improved.

Prabowo’s visits to Islamabad and Moscow in December also came under heavy criticism as the country was still struggling to recover from flash floods and landslides in Sumatra that killed more than 1,000 people.

Prasetyo said that the December trips were made after Prabowo visited affected areas twice and ensured that relief efforts were underway.

Prasetyo also highlighted that Prabowo stopped by affected areas on his way back to Jakarta from overseas.

But still, some analysts believe that the president should not have left the country on both occasions.

“Prabowo’s overseas trips have indeed become a major issue. How is it possible for Indonesia’s president to leave the country when a disaster is unfolding and recovery efforts have not yet been fully completed?” said Kunto Adi Wibowo, executive director of the political research firm KedaiKOPI.

“Prabowo has also failed to show sensitivity. In my view, this must become an important point of evaluation for the Prabowo administration.”

In October, Prabowo’s approval rating stood between 77 per cent and 83 per cent, according to surveys conducted by several research firms ahead of his one-year mark in office.

Experts said Prabowo’s remarks, for example praising palm oil - the sector widely blamed for exacerbating the flooding - and overly optimistic claims by senior officials have stirred controversy and clashed sharply with conditions on the ground.

At the same time, economists warn of a challenging economic outlook, with Trump’s tariffs expected to put pressure on Indonesia’s commodities and manufacturing sectors.

“People are worried about the economy. They worry about their family’s future, their financial situation and their livelihoods. These are what matter most to them,” said Hendri Satrio, a political communications lecturer at Paramadina University.

The World Bank echoed these concerns in its latest Indonesia Economic Prospects report, released on Dec 16. It noted that real wages have been trending downward since 2018 and that while employment rose by 1.3 per cent between August 2024 and August 2025, most of the gains were concentrated in lower-paying sectors.

These trends, the World Bank said, are weighing on household consumption, which accounts for around 54 per cent of Indonesia’s US$1.44 trillion gross domestic product.

Hendri said Prabowo could regain public confidence if he succeeds in translating his intensive overseas diplomacy into tangible economic benefits at home, particularly job-creating investments.

“If the economy improves, people will support Prabowo’s many international visits,” he said.

But some analysts added that Prabowo’s ambitions extend beyond simply attracting investment and cooperation that would benefit Indonesia economically.

“Prabowo wants to bring Indonesia to a prominent role in the international arena. He wants Indonesia to be respected and play a role in international diplomacy,” said Made of Singapore’s ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

To achieve that, experts argued Prabowo needs a Cabinet and advisory team he can fully rely on, particularly to manage domestic affairs while he is overseas.

“Prabowo needs to reform his Cabinet, and then reform his advisers because one of the biggest things which can foil Indonesia’s ambition to become a middle power is domestic instability,” said Rezasyah of Padjadjaran University.

Prabowo must also know when to be hands-on and when to delegate, said Hikmahanto of the University of Indonesia. He added that the president needs to listen more closely to his team, especially on complex issues, to ensure Indonesia’s messaging remains consistent.

“The president needs to engage in self-reflection and recognise that spontaneity is not acceptable,” Hikmahanto said, referring to Prabowo's tendency to make seemingly off-the-cuff remarks.

As great-power rivalry and weakened multilateralism threaten to further fragment the world, analysts cautioned that advocating peace and unity is becoming harder even for established middle powers — let alone emerging ones.

“Prabowo has proven that he can make friends with anyone. But the biggest challenge is to show that Indonesia is trustworthy and reliable and that requires consistency, competence and institutional strength,” Rezasyah said.

“Can Prabowo translate ambition into lasting credibility for Indonesia as a middle power? Only time will tell."