‘I thought about quitting school’: Pandemic takes a toll on Indonesia undergraduates as depression cases rise

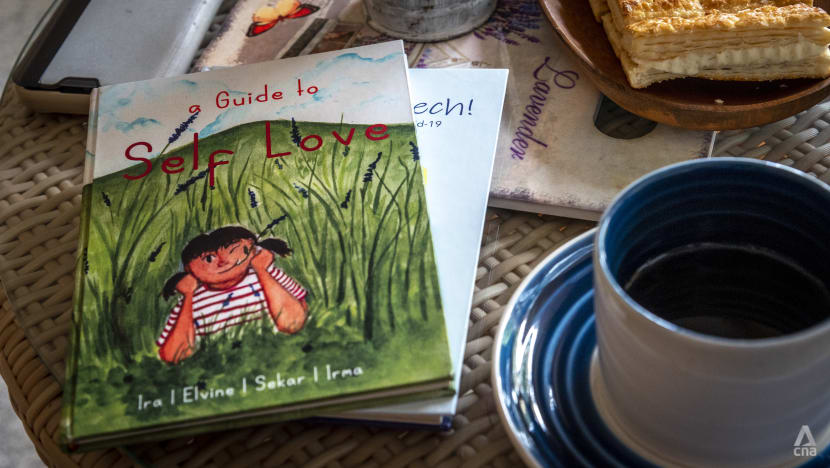

Fine arts lecturer Ira Adriati shows photos of seemingly random objects and people to help university students share their depression. (Photo: Nivell Rayda/CNA)

BANDUNG, Indonesia: Suryo (not his real name) used to believe that he was a bright student.

He was the first in his family to go to college and the first in his village to get accepted to a top university in the outskirts of Jakarta, 350km away from his home in Central Java.

But that notion immediately changed when he set foot at his university where he had to compete with top students, Mathematical Olympiad champions and award winners from all over Indonesia.

“Suddenly, I was a mediocre student,” Suryo told CNA.

The burden of coming from a poor family added more pressure. “My parents told me I have to graduate fast. I have to have good grades so I can get a good job and help my brother and sister,” he said.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic happened just as he was entering his second semester, which made things worse.

All in-person classes were suspended. Fearing a nationwide lockdown, his family requested him to go back to his village.

But the village had bad Internet reception while his poor family barely had enough money to buy him a secondhand laptop which he needed to conduct remote learning.

“I never owned a laptop before. I don’t really know how to use them. You can say I was technologically challenged,” he said.

As a result, Suryo often missed classes and was falling behind on some of his assignments. There were no friends to have after-class discussions with. No library where he can read books to catch up on his lessons. His grades were declining so badly he was on the verge of losing his scholarship.

Afraid of disappointing his parents, who had high hopes for their first son, he kept the problem to himself.

“I thought about quitting school. I even contemplated quitting life altogether,” he said.

“I couldn’t see a bridge without thinking of jumping from it. I couldn’t see a river without thinking of drowning myself.”

A study initiated by mental health advocacy group Ruang Empati, which was released in October, showed that 59 per cent of the 3,901 university students in Indonesia surveyed displayed signs of clinical depression.

It is a significant rise from the early days of the pandemic. A 2020 study by Ruang Empati showed the figure was 47 per cent.

In a previous survey in 2016 by a team of psychiatrists in Bandung, 30 per cent of the 400 scholarship recipients in the capital of West Java exhibited signs of depression of varying degrees.

According to this year’s survey by Ruang Empati, 13 per cent of the respondents said they have contemplated suicide. Three per cent of those surveyed said that they have attempted to end their lives.

“Multiply that with the number of students in Indonesia,” psychiatrist Teddy Hidayat, the founder of Ruang Empati, told CNA. Government statistics stated that there are 8.3 million university students across the country.

“The magnitude and urgency of the problem has become so big it deserves a lot of attention,” he said, highlighting that news of suicide among university students has become “more and more common” since the pandemic began.

In October, a student in Palembang, South Sumatra, leapt to her death from the third storey of a shopping mall. Three weeks later, a student in Yogyakarta was found dead in her dormitory after ingesting rat poison.

A month before, a student in Makassar, South Sulawesi, hung herself at her home while her parents were away. Also in September, a student in Malang, East Java, tried to jump off a bridge before she was saved by a passing police officer.

“Students need urgent attention because they are the future of this country. They are the future leaders of this country. Without (attention) they might suffer mental health problems, which not only affect themselves such as low academic achievements, but also create a loss for society and the country,” said the psychiatrist.

PANDEMIC AND ISOLATION

The pandemic has caused many people to feel a prolonged sense of anxiety, which when left untreated can lead to frustration and depression, Hidayat explained.

The declining economy which cost the jobs of thousands of workers has also added to the feeling of helplessness and hopelessness.

And then there were activity and social restrictions which the psychiatrist said made people feel isolated, with little means to vent their frustrations and anxieties through leisurely activities or interactions with others.

Elvine Gunawan, a psychiatrist who has been treating university students with mental health problems, said that although the pandemic has affected everyone, university students seem to be more at risk.

“Emotionally they are at a turbulent age. They are going through a transition period from a teenager into an adult. Academically, they have to think more abstractly. They have to learn to be more independent. Whereas before, they rely on their parents for comfort and protection,” she said.

Nizam, the Education Ministry’s director general for higher learning, admitted that university students have been feeling depressed during the pandemic.

“Schools and campuses are not only a place to study but also a place to socialise and interact. These two cannot be replaced through online learning,” the director general, who like many Indonesians goes with one name, told CNA.

“The pandemic has dragged on beyond what anybody has anticipated. This prolonged condition would of course lead to boredom and anxiety and if not managed well can lead to stress and depression.”

Firman Islami, a mental health peer counsellor at one of Indonesia’s leading universities, said throughout the pandemic, more and more of his fellow undergraduates have reached out to him about the anxieties and depressions that they have suffered.

“The pandemic has been challenging for everyone. You have a sudden and drastic change of lifestyle. There are those who are not coping as well as others. Not everyone comes from a harmonious family and when they spend too much time at home, fights occur,” the Bandung Institute of Technology student told CNA.

Meanwhile, there were others who have been struggling academically because of poor Internet connection or those who cannot study in peace because they have to share bedrooms with their siblings. Some students also have to work because the pandemic is taking a toll on their family’s economy.

The biggest problem, however, was isolation.

“Before the pandemic, people heal easily just by going out with friends. They can easily let off some steam by hanging out. You can’t do that now. Some people feel that they have no one to talk to. They feel they have nowhere to go to get help,” he said.

He added that peer counsellors like himself have also been struggling to reach out to those who needed help due to lack of face-to-face interaction. It was difficult to detect students who may need counselling when they were studying remotely.

Another peer counsellor, Maya (not her real name) said being unable to help fellow students in need also took its toll on her own mental health.

“There are students who used to be cheerful and enthusiastic and since the pandemic have shut themselves out. At campus, they can immediately seek help from friends or (on campus) psychiatrists. It can be quite scary at times. We don’t know how impulsive they can get when following these dark thoughts running around their heads,” Maya told CNA.

Maya, who was once diagnosed with several mental disorders and survived multiple suicide attempts before becoming a counsellor, began to relapse.

“It has been a struggle for me. I thought maybe I am not fit to be a facilitator because I couldn’t help my friends. I was in their shoes once. I was like that for a while. It left me feeling so anxious I ended up having to call my psychiatrist again,” she said.

“(The psychiatrist) told me that I need to set emotional boundaries. I was told that my job (as a counsellor) is to listen to their problems, interact with them and make suggestions. But their problems are their problems, not mine.”

CHALLENGES ABOUND

Gunawan, the psychiatrist, said many students have been unable to seek the help they need because the social stigma against people with mental health problems is still strong in Indonesia.

“The students themselves are more aware (of mental health issues) and they are willing to speak up and seek help. But they are at an age where they still need their parents’ consent for a medical treatment,” she said.

Arlisa Wulandari, a lecturer from Ahmad Yani University’s medicine faculty in Bandung, agreed that some parents are reluctant to give medical consent for mental health treatment.

“Many parents are in denial. They don’t want to acknowledge that their children are suffering from depression. They don’t want to be seen as bad parents. They don’t want to have mental illnesses (listed) in their children’s medical history because they worry it will hurt their chances at getting jobs,” she told CNA.

Gunawan said by the time some parents let their children seek professional help, it was too late.

“Most students come (to be treated) when their cases have become severe. When they are already failing academically. When they have already attempted suicide and so on. It is harder for a psychiatrist to treat them when they are already at that stage,” she said.

Gunawan said universities should do more to detect signs of depression among their students and prevent their illness from worsening.

Nizam, the Education Ministry’s director general, said universities are required to set up their own counseling services for these purposes.

“In general, our universities have counseling services, be they in the form of a dedicated unit or facility or counsellor lecturer,” he said.

But Ruang Empati founder Hidayat said there have been no uniform standards for these counseling services, most of which operate without the presence of a trained, on-campus psychiatrist or psychologist.

“There are those which do (have trained professionals). There are those which exist but don’t have (on campus psychiatrists). There are those which exist in name only and there are (universities) which don’t have any counseling services at all,” he said.

Hidayat said the universities with on campus psychiatrists and trained student volunteers are the exception, not the norm.

“At most universities, it is the students who initiate their own counseling services or support groups. Ruang Empati has been providing training for these volunteers,” he said.

To help students mitigate the mental health problems they experienced, Ruang Empati has been providing online consultation services since the pandemic began, employing more than a dozen volunteers to act as counsellors.

The group also provided art classes for students to release some of the stress and express themselves.

“Art can serve as a therapy for them. Some people can release stress through singing or drawing. Tearing pieces of paper or scribbling can already help them cope with whatever they are feeling inside and communicate their thoughts through visual languages,” Ira Adriati, a fine arts lecturer who has been helping the group with its art therapy programme, told CNA.

“The goal is not to produce good works of art. But to make them feel better than the way they feel before.”

“LIFE IS BETTER FOR ME NOW”

According to the Education Ministry, deteriorating mental health among students was the main reason for reopening universities in October and introducing hybrid learning with a mix of online and in-person classes.

“Getting students back to campus will not only allow students to develop technical and people skills, which cannot be achieved through online learning, but also reinvigorate the social interactions needed to keep students’ spirit and well-being healthy,” Nizam, the director general, said.

The ministry has also enacted a regulation to eradicate sexual violence, bullying and intolerance, which Nizam said would eradicate some of the root causes of depression among students.

The government, he said, was also developing the so-called “Academic Health System” by making campuses more health conscious and environmentally friendly.

“We are pushing for a healthier, safer and more comfortable academic environment. If this is achieved, we will see healthier and happier students and academics,” he said.

Suryo said he is happy that his university has reopened.

He decided to return to Jakarta in September 2020, thinking that it would be better for his studies. For the past one year, he has been renting a room near his university so he can take advantage of the campus’s free Wi-Fi.

“The campus was quiet. It was like a ghost town. But there have been a number of students who decided to come back to Jakarta because they too were having problems with Internet connection back home,” he said.

“We don’t go to the same faculty. We are from different provinces. But we became close friends because of our shared problems: Learning remotely from our respective villages.

“Life is better for me now. It is a far cry from a year ago,” he said, adding that he eventually got his grades up and retained his scholarship.

“With my campus reopening, I think things will only get better for me mentally and emotionally.”

Where to get help:

National mental health helpline: 1771

Samaritans of Singapore Hotline: 1767

Singapore Association for Mental Health Helpline: 1800 283 7019

You can also find a list of international helplines here. If someone you know is at immediate risk, call 24-hour emergency medical services.