analysis Asia

Malaysia's 'aggressive' move to double minimum expatriate salaries sends 'strong' signal to hire local

Some employers are considering a “thorough review” of salary structures for current and future expatriates and, if necessary, the relocation of certain roles or workers to other countries.

Office workers near the Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KUALA LUMPUR: Malaysia’s proposal to raise minimum salaries for expatriates sends a strong signal to prioritise hiring local talent, even as it could reduce the country's business cost advantage and investment attractiveness, observers say.

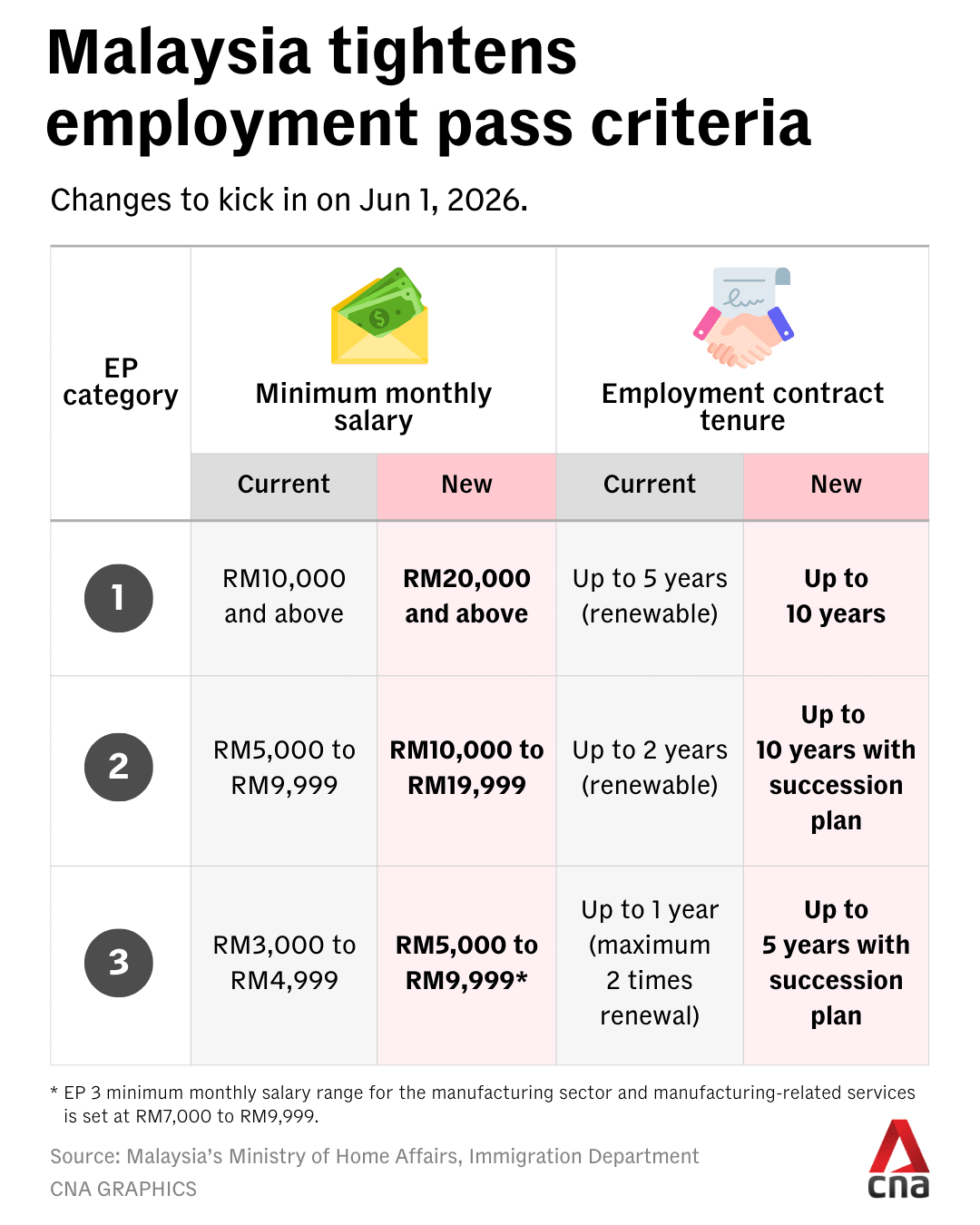

The Ministry of Home Affairs announced on Jan 14 that it will impose tighter requirements from Jun 1 on the hiring of non-locals across all three employment pass (EP) categories.

This is aimed at reducing dependence on foreign manpower and prioritising local talent over expatriates for job vacancies, the ministry said in a statement.

The minimum salary for Category 1 (top executives) will be raised from RM10,000 (US$2,471) to RM20,000. Meanwhile, the minimum salary for Category 2 (managers and professionals) will go up from RM5,000 to RM10,000, while Category 3 (skilled workers and technicians) will see an increase from RM3,000 to RM5,000.

The Malaysian government has not offered details on how it derived the quantum increases.

The Home Affairs Ministry said in a subsequent clarification document that the higher thresholds "ensure that the employment of expatriates is focused on high-impact expertise and does not replace roles that can be filled by the local workers".

On the justification for raising top executives’ salaries to RM20,000 - a 100 per cent increase from the previous amount - the ministry said that this tier covered "strategic positions and critical expertise that directly contribute to economic growth and technology transfer".

Malaysia-based economist Shankaran Nambiar told CNA that the higher thresholds were aimed at reducing dependence on foreign workers, ranging from the tech industry to machine operators and technicians.

"I'm not sure how (the Malaysian government) calculated it and why ... The government must want to change this situation for fear that otherwise there would be no strong incentives to hire domestic expertise," he said.

EXPATRIATES UNSURE IF EMPLOYERS WILL RAISE SALARIES

Joshua Webley, an expatriate from the United Kingdom who moved to Malaysia three-and-a-half years ago for his career, told CNA that members of the expatriate community have raised “some concerns” about the EP changes.

“Because obviously raising the bar that much … there's a lot of people that aren't going to hit that target,” said the 33-year-old, who together with his Malaysian wife manages a community called The Expats Club with 21,000 members.

“Not even from the expats’ point of view, but the employers’ point of view, a lot of people can't afford to pay those salaries.”

Employers are uncertain about the changes too, Webley said, adding that expatriates have not had the chance to ask about issues like contract renewals given the announcements were made only recently.

These include those working in international schools, Webley said, noting that teachers in even the most prestigious schools in Malaysia might not be able to earn the minimum RM20,000 salary for a Category 1 EP.

“And to be fair, RM20,000 is a lot for a teacher to earn globally as well,” Webley said.

Under the new rules imposed by the government, Category 2 and Category 3 EPs will require employers to show a “succession plan”.

This is defined by the government as a “structured plan to transfer knowledge and expertise to local employees within the expatriate's employment period”.

Webley noted that countries including Malaysia have always set up their expatriate visa regimes to be stringent enough to ensure the quality of foreign workers, and that they do not take jobs from locals.

Similar concerns were seen in a public social media group for expatriates in Kuala Lumpur. One user said he holds a Category 2 EP and the changes mean he needed to find a better-paying job urgently.

"I think it makes sense for the national development of talent but the very aggressive nature of the increase isn’t well executed: Doubling Cat 1 and 2 is too much too soon - will only punish Malaysian employers,” wrote another.

Nambiar, the economist, said companies with Category 2 and Category 3 employees could face rising costs and be forced to shift some of their operations to another country where labour supply for specific skills is "abundant and cheaper".

These include those in outsourced business services like content moderation or language-specific customer service, as well as engineering and information technology (IT), observers said.

While Nambiar believes the policy changes are not “serious enough” to prompt mass relocations, he said they might factor into how companies select investment locations.

“It will also work to discourage certain types of investments from coming into the country,” he said, referring to sifting out low-value portions of a production supply chain, for instance the moulding and printing process in toy manufacturing.

“I think there is a sense that the government can be more selective about investments and change the industrial landscape.”

Meanwhile, Arulkumar Singaraveloo - who is the chief executive officer of the Malaysia HR Forum which trains human resource professionals - acknowledged that the changes might “slightly temper” Malaysia’s cost advantage for certain foreign companies.

“But by aligning with regional benchmarks and emphasising high-value foreign talent, the country can maintain competitiveness while advancing its human capital agenda,” he told CNA.

WILL MORE JOBS BE FREED UP FOR LOCALS?

Malaysia’s plans to tighten its EP regime follows similar moves in the region to ensure the quality of expatriates and protect local jobs.

In 2025, Thailand tightened its Board of Investment (BOI) visas, typically issued to skilled expatriates, by specifying minimum salary thresholds for executives, managers and operators.

Executives are required to earn at least 150,000 baht (US$4,779) a month, managers between 50,000 baht to 75,000 baht a month, and operators between 35,000 baht and 50,000 baht a month.

Previously, Thailand did not officially state salary thresholds for these visas, although it was understood that the standard minimum salary for most foreigners in BOI companies is 50,000 baht.

The new minimum salaries specified by Thailand are slightly lower than the new thresholds for Malaysia’s EPs.

In 2025, Singapore raised its minimum monthly qualifying salary for new EP applicants from S$5,000 (US$3,895) to S$5,600 for most sectors, lower than the new threshold for Malaysia’s Category 1 EPs. Foreigners hoping to work in the financial sector in Singapore, however, have to earn a minimum of S$6,200 a month.

The same year, Singapore also raised the minimum salary for its lower-tier S Pass from S$3,150 to S$3,300, slightly higher than the new threshold for Malaysia’s Category 2 EPs.

Singapore benchmarks its EP minimum salaries to the top one-third salaries of local professionals, managers, executives and technicians by age. For the S Pass, it refers to the top one-third salaries of local associate professionals and technicians by age.

According to Malaysia’s official statistics in 2024, local managers and professionals earned an average monthly salary of RM7,121 and RM6,524 respectively, while local technicians and associate professionals earned RM4,077 on average a month.

This suggests the country’s EP changes were also designed to peg expatriates' remuneration to the higher end of local top earners.

Socio-Economic Research Centre executive director Lee Heng Guie said "there is no universal benchmark" on how much to raise minimum expatriate salaries, and that these often depend on the job scope, level of competency, and national economic goals.

The minimum RM20,000 monthly salary for top-tier expatriates makes it less cost-effective for companies to hire foreign talent for roles that local professionals are capable of filling, reducing "crowding out" in the job market, he told CNA.

Singaraveloo from the Malaysia HR Forum said some firms might initially adjust to the new thresholds by raising compensation for key expatriate roles.

“But over time, the combined pressure of higher costs and tenure limits will make it more compelling to invest in developing Malaysian talent internally or through targeted recruitment,” he said.

Among the changes to Malaysia's EP regime, the government will also impose fixed contract tenures for all categories: up to 10 years for Category 1, up to 10 years with a succession plan for Category 2, and up to five years with a succession plan for Category 3.

Previously, employment pass contracts were capped at between one year to five years, although renewals were allowed without the need for succession plans.

But economist Geoffrey Williams, director of Williams Business Consultancy, said the claim that expatriates are taking jobs from locals is not true.

"Firstly, there are too few expatriates to make that claim meaningful. Secondly, it is already costly to pay for visas, so they are not competitive in a cost sense," he wrote in a post on LinkedIn.

"Thirdly, expatriates are employed for very specific reasons based on experience and expertise. This will not change."

The Malaysian Immigration Department issued 180,812 EPs - including new applications and renewals - in 2025, up from 160,380 passes in 2024. Malaysia had 17.06 million employed people in October 2025.

Williams told CNA it is not so much the comparison to regional countries that counts, but the way it has been communicated - “that Malaysia does not want expats somehow”.

These changes have sparked fears among the expatriate community of being forced to leave once their contracts end, despite past contributions to local jobs and the economy.

In its clarification document, the Home Affairs Ministry said contract extensions will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis based on "national interest".

"Stability is also important. If it changes too much you cannot plan long-term and if the visas are short then you don't invest or commit here," Williams said.

“NO CHOICE BUT TO FOLLOW”

Sasha Reddy, Malaysia partner at Vialto Partners, a global mobility firm, told CNA that its clients operating in Malaysia have responded to the proposed change with a mix of immediate workforce adjustments and longer-term strategic planning.

“Some have raised concerns about increased operating costs, potential losses in productivity and innovation, and risks to business continuity,” she said.

“These concerns are particularly pronounced in niche and highly specialised areas such as advanced engineering, high-end manufacturing, digital transformation, and energy transition, where the local talent pipeline remains limited and businesses have traditionally relied on expatriate expertise.”

Vialto’s clients in Malaysia include multinational companies (MNC) and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in industries like financial services, oil and gas, digital transformation, manufacturing, electrical and electronics, and global professional services.

To minimise disruption to business operations, companies are reassessing recruitment strategies to strengthen local talent hiring, and, where necessary, the relocation of certain roles or employees to other countries, Reddy said.

Companies are also evaluating a “thorough review of salary structure” for both current and future expatriate populations compared to local talent availability, and the implementation of training programmes to support local succession planning.

“At the same time, companies have expressed cautious optimism about the policy’s long-term objectives,” she added.

“Over time, this approach is expected to help build a sustainable pipeline of local professionals capable of filling senior and specialised roles, ultimately enhancing local earning potential and supporting Malaysia’s long-term economic competitiveness.”

SME Association of Malaysia national president Chin Chee Seong told CNA that the EP changes will “definitely” hit SMEs that already face cost pressures but cannot find local workers for skilled roles.

Most affected will be IT firms that hire skilled workers from countries like India and Vietnam, as well as manufacturing and engineering firms with production lines, he said.

“If they really need these foreign workers, they have no choice but to follow (the new rules) … There will be additional costs for them,” he said.

To minimise undue economic burden, Chin called for EP minimum salary hikes to be frozen or lowered for SMEs. “It’s a bit tough for them at the moment,” he added.

To protect SMEs, the Home Affairs Ministry said these firms will be granted “transition periods and flexibility” through structured engagement sessions and clear implementation guidelines.

A Singapore SME that hires some non-Malaysians in Johor told CNA it understands the need for the minimum salary changes.

“I feel this approach is balanced. It does not strangle the industry and is pro-growth, yet takes care of Malaysians,” said Steven Kang, managing director of energy services company Measurement and Verification.

The company has about 50 employees in its Johor Bahru office, five per cent of which are non-local managers on Category 2 EPs.

Kang said he will raise the salaries of his EP employees once the changes kick in, a justified move given their new wages will be comparable to what they would be earning in Singapore.

The plan is to eventually transition to a fully Malaysian engineering workforce that the firm will train in-house, with the non-Malaysians returning to roles in Singapore.

Kang said these employees did not approach him with any concerns about the EP changes. “We plan long-term with these staff (members) and trust level is high,” he added.

Webley, the expatriate from the UK, said it is normal for expatriates to experience “a little anxiety” when EP changes are announced, especially for those with families who have uprooted their lives to come to Malaysia.

But he agreed with Malaysia’s EP changes, saying that they will protect local livelihoods and attract higher-quality foreign talent.

"If people can meet the minimum standards, it's not going to affect their decision on moving here,” said Webley, who told CNA he worked in more than 40 countries before settling down in Malaysia.

“It’s a blessing for us to be here, not the opposite way round.”