The flood factor in Malaysian elections: Will it prove costly for Barisan Nasional?

The recent ‘once-in-100-years’ flood and the ongoing monsoon have added to the usual issues in Malaysian politics. The programme Insight explores the possible impact on the outcome of this general election.

The start of the monsoon season has stoked fears in Malaysia of impending floods.

KUALA LUMPUR: When flood waters entered his house last December, Shah Alam resident Selvakumar and his family braved the currents to seek shelter at a school a couple of hundred metres away.

But at the school, they were left stranded for two days without food and water. That is why he was “angry” and “disappointed” — he felt that the government’s response and aid for the flood victims were inadequate.

“Luckily, there was one Malay lady who gave us a piece of chicken. But there were other families who hadn’t eaten,” recalled the 46-year-old. “We almost cried because we were too hungry … We were so depressed.”

“It was really bad … We couldn’t even ask for help … No politicians came to help us.”

Eight of Peninsular Malaysia’s 11 states, plus Kuala Lumpur, were hit by the “once-in-100-years” flood, which left 54 people dead and required the evacuation of about 400,000 people. Selangor, where Shah Alam is located, was the most affected.

The floods have added another dimension to Malaysia’s general election and to the usual issues, like cost of living and race, that surround Malaysian politics — especially with the Nov 19 polls coinciding with the annual monsoon season.

“If any disaster happens, and if the disaster response fails or doesn’t meet the expectations of the people, the voters will naturally be angry with the incumbent,” Adib Zalkapli, a director at strategic advisory firm BowerGroupAsia, told the programme Insight.

The start of the monsoon season last week — it is expected to last until March — has additionally stoked fears of impending floods and set some residents on edge.

One of them is retiree Phua Thiam Hwa, 67, a resident of Kampung Kasipillay in Kuala Lumpur, another area that bore the brunt of last year’s floods.

Every time it rains now, he makes a point of visiting the canal located a few hundred metres from where he lives. “If the rain doesn’t stop, we’d be afraid,” he said. “We’d check the water level of the (canal).”

Already, less than a week after Malaysia’s parliament was dissolved on Oct 10, heavy rains caused flash floods in Penang and Perlis. This followed similar floods in Kuala Lumpur early last month.

And during the campaign period, floods hit six states — Johor, Kelantan, Melaka, Penang, Perak and Selangor — with around 3,200 victims evacuated as at Wednesday morning.

As early as September, the Malaysian Meteorological Department (MetMalaysia) had warned of heavy rains at year end.

“The prediction is that the amount of rainfall that we’re going to receive during the coming north-east monsoon season is roughly about the same as what had occurred last year,” said director general Muhammad Helmi Abdullah.

“But the impact — whether it’s going to be heavy flooding, whether it’s going to be just a moderate type of flooding — is beyond our predictive capability.”

The question now, ahead of polling day, is whether the decision to hold the elections eight months before the parliamentary term was to expire will pay off for the ruling coalition. Or will the monsoon, and the memories of last year’s floods, cost it votes?

A CALCULATED RISK

The reason behind the timing of the elections is a political one, according to observers.

WATCH: Will monsoon polls benefit the ruling Barisan Nasional? (46:35)

“This is the time when the opposition is yet to be united. If you look back at 2018, elections were called at a time when the opposition was already … projecting a united front,” noted Adib.

“I guess a bigger risk for Barisan Nasional is to wait until the opposition is united.”

The six-decade rule of the United Malays National Organisation (Umno) ended in 2018. But in the years since, politicking returned Barisan Nasional and its largest component party to power, even as ex-Prime Minister Najib Razak has been convicted of graft.

“They’ve seen Najib’s gone to jail — and so I suppose — with the expectation that … if they don’t win, then more people are going to be charged,” said Southeast Asian Studies lecturer Serina Rahman at the National University of Singapore.

“The assumption is that they’re trying to hasten things so that they can calm down the situation and … get control of the Cabinet and Parliament, because now they don’t have complete control.”

Traditionally, a lower voter turnout also benefits Barisan Nasional, and heavy rains might affect turnout. Umno information chief Shahril Hamdan disagrees, however, that his party would like such an outcome.

“I don’t think it’s as simple as ‘the lower the turnout, the better it is for us,’” he said.

That suggests that we want a lower turnout. I personally don’t and haven’t heard any of my colleagues in the party, openly or even privately, saying we want a lower turnout. That’s not really how democracy works.”

At the last election, turnout was a high 82.32 per cent. But inclement weather could indeed keep some citizens from turning out this time.

“If there’s no rain, I might go out and vote. But if there’s rain, I might take care of my family, and we stay at home,” said Errol Teoh, a resident of Klang, Selangor.

“Elections might affect the whole country, but this is about life.”

MetMalaysia expects only the federal territory of Putrajaya to enjoy good weather all day tomorrow, and he is bracing himself for the worst after sustaining estimated losses of RM60,000 (S$18,000) when flood waters filled his optical shop last December.

Just 800 metres from Teoh’s shop, Benson Tan also took a hit — to the tune of RM100,000 — and almost lost his motorcycle spare parts business, which he had spent 20 years building up.

To the 63-year-old, the elections are not well timed.

“The main purpose of elections is to select our Members of Parliament as well as state assemblymen to assist us. But if (there’s heavy rain or) flooding, how are we going to select them?” he questioned. “Very bad. I disagree.”

The ruling party, however, is confident that it had accounted for floods when it made election plans, which included provisions within the law for the Election Commission to delay the polls.

“We should have faith in the agencies involved in flood relief. And any rescue efforts or any flood management issues will be managed despite any elections being held,” stressed Shahril.

“This isn’t to say we’re not concerned, but I think it’s something that we can manage.”

Riding the momentum of back-to-back wins in state elections — for example, in Johor in March and in Melaka last November — the incumbents have taken a calculated risk in calling the polls now.

“If there’s no storm and there’s no flood, then perhaps people will turn out,” said Serina. “If there’s a low voter turnout, the ones who’ll turn out, no matter what — fire, storm, hail — are the Umno supporters.”

ADEQUATE GOVERNMENT RESPONSE?

The monsoon polls could be a double-edged sword, however, used by the opposition to point to the government’s failures.

“When the dissolution (of parliament) took place, it showed that (politicians) didn’t care much about the lives of people or about the potential victims during the monsoon season,” said Malaysian United Democratic Alliance president Syed Saddiq Syed Abdul Rahman.

“It just shows that politics comes … before welfare.”

Democratic Action Party incumbent MP Hannah Yeoh thinks there might be fresh “anger” among voters going through flooding now. “The flood severity isn’t like the December 2021 (floods), but … it’s already happening in different parts of Malaysia,” she noted.

Last December, when flood relief was slow to come, people had to take matters into their own hands, “going in with their own boats … to save people from rooftops, to provide food aid (and) medical support”, Syed Saddiq pointed out.

“When you rely on … the average Malaysian to save lives, it shows that there’s a clear state failure.”

Shahril, who is also a Barisan Nasional candidate for a federal seat, acknowledged the “weaknesses” in the government’s response “in terms of the speed” then. “Maybe the first 24, 48 hours could’ve been better,” he said.

“But I think we learnt quickly, and … in terms of the amount of cash aid to victims, home repairs, new homes being built, that was also unprecedented … We responded seriously and in a big way.”

After last year’s floods, which caused overall estimated losses of RM6.1 billion, the government pledged RM1.4 billion in flood relief, including up to RM5,000 in cash per affected household for home improvement works.

And how the government has responded since the floods is something voters would have seen. “There’d be anger especially if there’s been no improvements in infrastructure,” said Serina.

“But from what I see, I think the local agencies are doing what they can to make sure the drains are cleared … so some areas that are regularly flooded are now flooding a bit less.”

Still, there is perceived inaction. Phua the retiree said nothing had been done for 10 years to clean the canal near his home, even though it was “full of rubbish” that blocked its flow and “led to floods”.

“Then I saw an excavator at the riverside for a few months but no cleaning work done. Only recently did I see them cleaning up,” he said

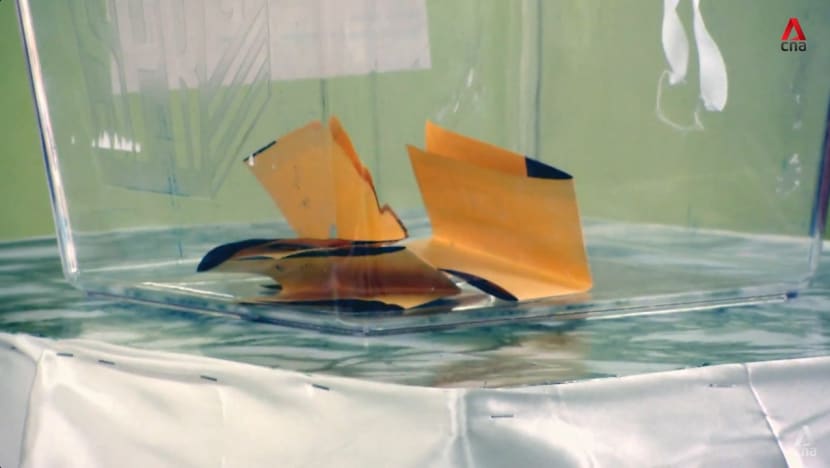

In the flood-prone Klang Valley, rows upon rows of sandbags also line riverbanks and canals. They are meant to divert flood waters from homes and commercial spaces in the event of heavy monsoon rains.

But Yeoh said that when she inspected them, there were “already broken” sandbags. “Sandbags are placed on only one side of the river, sandbags aren’t blocking the entire stretch, there are … gaps in between,” she continued, declaring this solution ineffective.

On this issue of flood mitigation efforts, Selangor state government management services secretary Muhamad Shah Osmin said: “The sandbags are placed there … so that water levels won’t rise. If they’re no longer functioning, they’ll be replaced.

“We’re also conducting some drainage works to deepen the rivers to ensure these rivers and canals aren’t choked. We’ll do everything to allow for water to flow smoothly and for the water upstream to flow downstream more rapidly.”

In the nation’s capital, there are plans for a flood wall at flash flood hotspots, which will replace the sandbags eventually. And at the federal level, the government will implement a RM15-billion flood mitigation plan from next year until 2030.

READY FOR THE NEXT BIG FLOOD?

Whatever happens at the polls, floods like the one last year could recur.

Although Malaysia lies outside the historical cyclone paths — which has made it relatively safe from a direct hit — tropical depressions and typhoons will occur more frequently as sea waters warm. And the country cannot shield itself from the monsoon rains.

A report published this year by C40 Cities, a global network of nearly 100 cities combating climate change, found that Kuala Lumpur would face a severe increase in stormwater flooding by 2050 under the highest baseline-emissions scenario.

Preparing for the risks will require both investment and infrastructure redesign.

“If you don’t have enough green, open spaces with soil as ground cover (instead of tarmac), where do you think the water will go?” said Malaysian Urban Design Association president Shuhana Shamsuddin. “The rivers will be swollen.”

Long-term climate mitigation means “big infrastructural solutions”, agreed Serina. That also means political will is required, “because it inconveniences a lot of people”, she said. “This is the issue, right? These things take time.”

But does Malaysia have time on its side while the government looks at ways to prevent future flooding?

The combination of La Nina conditions — expected to persist until the year end — and high concentration of water vapour, added to the north-east monsoon, “possibly can cause a big flood”, warned Universiti Teknologi Malaysia environmental hydrology professor Zulkifli Yusop.

“And if that happens during high tide, the situation will be much worse.”

The issue for Shuhana is that “there’s a lot of talking, but what we need in Malaysia is to walk the talk”. Sustainability, as she put it, “is about the mindset and the culture”.

She has yet to see a comprehensive solution being provided or any “dramatic” change, only short-term measures. “Observing the points where there are flash floods … is just a firefighting approach, a very ad hoc basis,” she said.

“There should be a long-term strategy (for dealing) with these climate issues … Why wait for the disaster to happen before you do something?”

It is a sentiment that Selvakumar shares. “I want the government to do something before anything happens. Don’t wait,” he said.

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.