Commentary: When it comes to AI, Budget 2026 marks a shift from aspiration to execution

By naming sectors and framing missions, Budget 2026 shows how Singapore intends to turn AI into meaningful productivity gains, says NUS Business School’s Sumit Agarwal.

File photo of software developers writing code. (File photo: iStock)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Over the past year, artificial intelligence (AI) has been everywhere – in policy speeches, boardrooms, university seminars and dinner conversations.

At some point, repetition creates fatigue. Not because AI is unimportant, but because the conversation can start to feel generic. When everything is about AI, nothing feels concrete.

That is why the announcements in Budget 2026 are more significant than they appear to be.

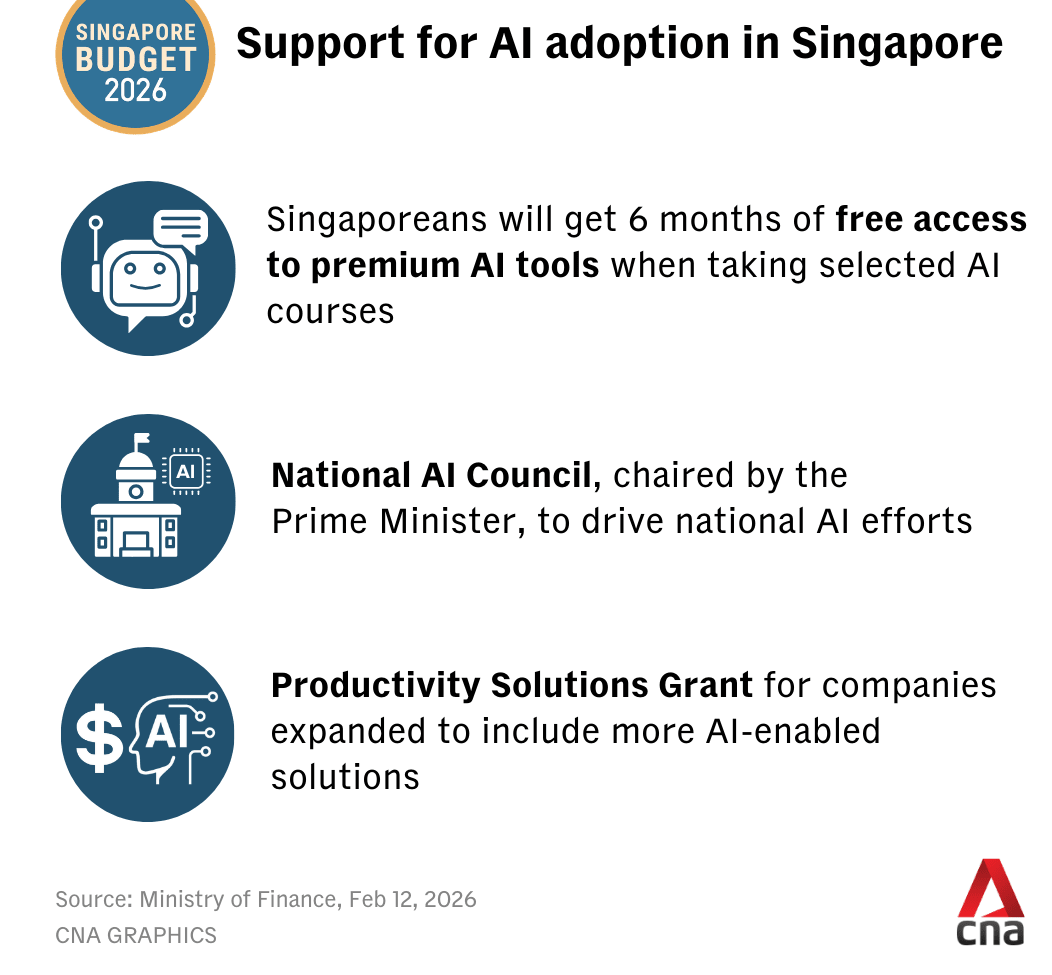

The decision to establish a National AI Council chaired by Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, together with selected “AI missions” in advanced manufacturing, connectivity, finance and healthcare, marks a shift from aspiration to execution.

This is not simply about declaring AI a national priority. It is about choosing where Singapore intends to compete and organising the system to deliver.

DEFINING A DIRECTION

The selection of the four sectors is deliberate.

Advanced manufacturing reflects our strengths in precision engineering and high-value production. Connectivity reinforces Singapore’s position as an air and sea hub, where reliability matters as much as innovation. Finance builds on a globally-connected financial centre where regulatory credibility is itself a competitive asset. Healthcare responds to demographic reality, while leveraging our strengths in clinical excellence and systems management.

By naming sectors and framing missions, the government is signalling that AI will not be pursued as a diffuse overlay across everything. It will be deployed deliberately where productivity gains and exportable capabilities can be meaningful.

The more interesting question is what the new AI Council must actually do.

Chaired at the highest level, the council recognises that AI is not a narrow technology issue. It cuts across issues ranging from manpower to education, regulation, data governance, cybersecurity, procurement and public trust.

Without coordination, agencies optimise locally and pilots fail to scale. The value of the council will not lie in producing another strategy document. Instead, it will lie in removing bottlenecks and aligning incentives.

INTEGRATION IS KEY

When it comes to AI, the hard part is not experimentation. It is integration.

That means addressing less glamorous constraints – fragmented data systems, limited interoperability, unclear procurement pathways and uncertainty around governance. Common architecture is what will turn AI from a collection of promising pilots into systemic innovation.

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong acknowledged that end-to-end AI transformation demands shared foundations, not piecemeal initiatives. That logic is central to proposals such as the Networks for Humanity Research Institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS), which seeks to establish open standards so financial institutions can modernise collectively, rather than in costly and incompatible silos.

In finance, in particular, the integration challenge is becoming structural. As AI evolves from analytics tools into autonomous agents allocating capital, executing compliance and interacting with markets, the underlying infrastructure must adapt. In this case, programmable, quantum-secure and interoperable systems will be prerequisites for stability in AI-driven markets.

TURNING AI ACCESS INTO PRODUCTIVITY GROWTH

The Budget also includes measures to spur adoption, including six months of free access to premium AI tools for Singaporeans who take up selected courses, alongside productivity support for firms.

These are sensible entry points that reduce friction and encourage experimentation, but access to tools does not automatically translate into productivity. The real gains come when organisations rethink workflows, redesign processes and integrate AI into core operations.

Many firms discover that the binding constraint is not access to a model. It is data quality, system integration and organisational readiness. Without addressing these, AI will remain an interesting add-on, rather than a transformative capability.

At the individual level, the same principle applies. Prompting skills are useful but durable advantage comes from combining domain expertise with AI fluency. The worker who understands both the workflow and the tool will outperform the one who simply knows how to operate the interface.

In line with this logic, discussions are underway for a new master’s programme at the NUS Business School. With a focus on AI in business, this will give professionals a structured way to build strategic capabilities to work with and alongside the technology.

This is why the deeper strategic question is whether Singapore can convert early AI adoption into sustained productivity growth – a necessity for a mature economy facing demographic constraints.

If deployed effectively in manufacturing, AI can raise output without proportionate increases in labour. In finance, it can strengthen risk management and compliance, while improving customer experience.

AI can help manage rising demand in healthcare without overwhelming human capacity, while in connectivity, it can reinforce our role as a trusted node in global networks.

With a prime minister-chaired council showing priority and sector missions signalling focus, the next thing to watch will be measurable outcomes. Are turnaround times falling? Are error rates declining? Are new AI-enabled products being exported? Are workers being redeployed into higher-value roles rather than displaced into uncertainty?

If Singapore can combine coordination, institutional capacity and speed, this may well be remembered not as another AI headline, but the moment when ambition became advantage.

Sumit Agarwal is the Low Tuck Kwong Distinguished Professor of Finance, Economics and Real Estate at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School, and the managing director of the Sustainable and Green Finance Institute at NUS. The opinions expressed are those of the writer and do not represent the views and opinions of NUS.