Commentary: Beyond Singapore Turf Club, where can we find more land for housing?

The Singapore Turf Club is closing down to free up land for housing. Property expert Nicholas Mak of Mogul.sg looks at what other types of real estate in Singapore are under-utilised and ripe for redevelopment.

SINGAPORE: The government’s announcement on Monday (Jun 5) that the Singapore Turf Club in Kranji will be closed by March 2027 to make way for more housing took many by surprise.

When that happens, more than 180 years of horse racing history in Singapore will come to an end.

The 120ha of land occupied by the racecourse will then be redeveloped and used for residences, including public housing, and potentially leisure and recreation purposes. Analysts estimate that the site may be able to accommodate between 20,000 and 40,000 homes, depending on the future plans for the area.

Over the past few days, many questions have been raised, including whether other types of land or buildings could also be taken over by the government for redevelopment.

CREATING MORE LAND

The compulsory acquisition of real estate by the Singapore government is nothing new.

Since independence, the government has used the Land Acquisition Act of 1966 to take over large tracts of privately owned land for redevelopment or simply for land-banking. Land owners can dispute the compensation from the government, but cannot legally refuse the government’s acquisition of their properties.

Such compulsory acquisition of land contributed to the government becoming the largest land owner in Singapore. The Land Acquisition Act was used more frequently in the 1960s to 1980s, which would explain the public’s surprise when it is used today.

Singapore, which has a total population of 5.64 million as at end-Jun 2022, has limited land. Since independence in 1965, the country’s land size has grown by 26 per cent to 734 sq km, through land reclamation.

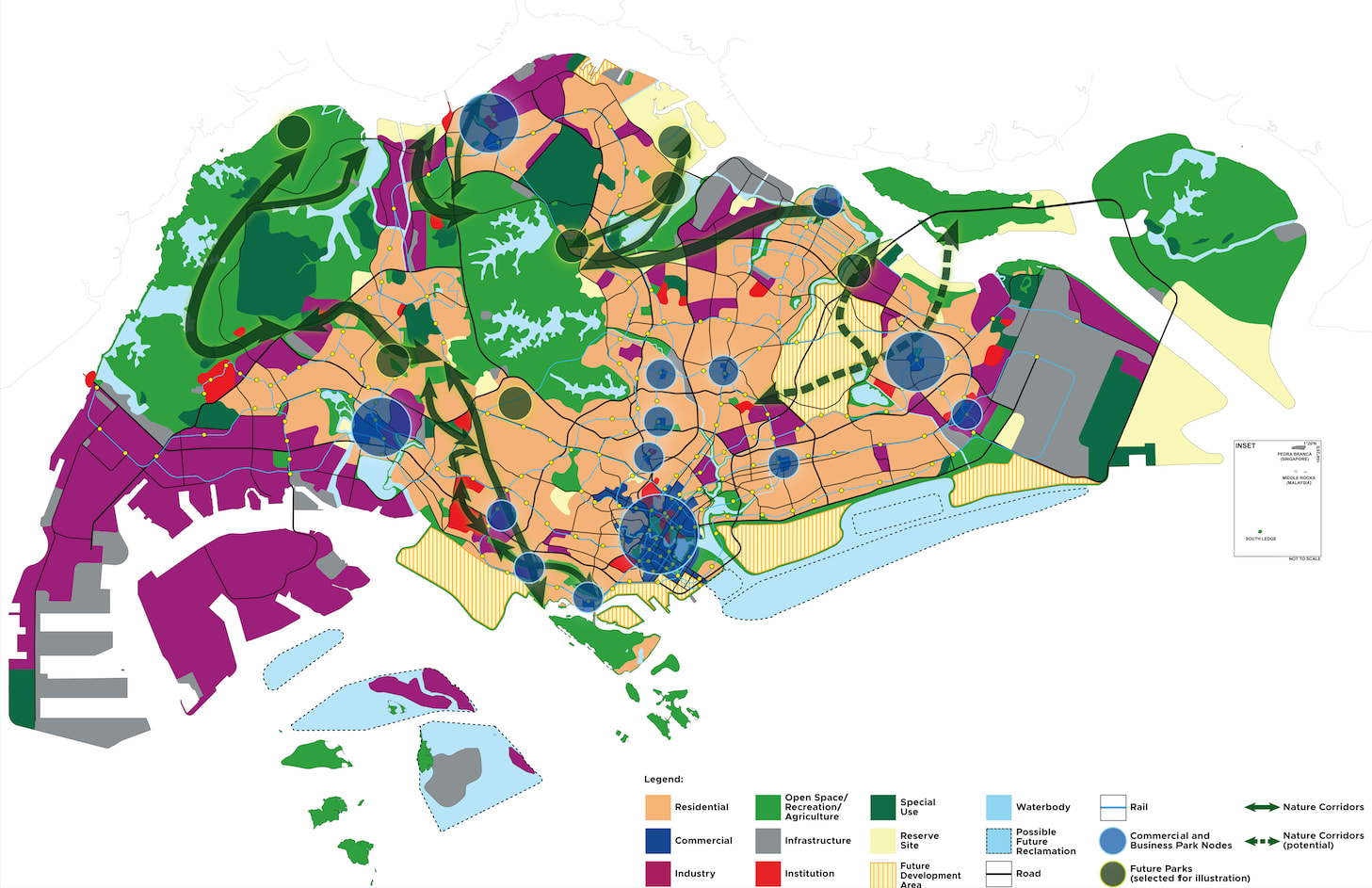

But it still needs more space. Based on the Land Use Plan in 2013, Singapore will need an additional 5,600ha of land by 2030 to cater for a population expected to grow to between 6.5 million and 6.9 million.

Demand for housing in Singapore has also soared despite several rounds of cooling measures, pushing private home prices up 8.6 per cent and Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats resale prices up 10.4 per cent last year.

One of the reasons cited by the government for the closure of the Kranji racecourse was the falling number of visitors to the premises. In typical Singaporean pragmatic manner, if real estate is under-utilised, then it should be put to better use, especially on our land-scarce island.

This raises the question: Which other types of real estate in Singapore are under-utilised and ripe for redevelopment?

CAN GOLF COURSES, INDUSTRIAL SITES MAKE WAY FOR HOUSING?

Golf courses are among the properties suggested by many.

As of 2023, there are 13 private golf courses and three public golf courses in Singapore, taking up about 1,456 ha or about 2 per cent of the total land area.

While an additional 356ha of golf course land will be taken back for redevelopment by 2030, including the Marina Bay Golf Course, there are still sizeable swathes of land left being used for golf courses.

Based on the Singapore Golf Industry Report, about 80,000 residents in Singapore play golf. This means that only about 1.4 per cent of people living in Singapore occasionally use these facilities. The other 98.6 per cent of the people are excluded from using or even taking a stroll on these sites because they are private properties.

Since golf courses take up significant amount of useable land and they are inaccessible to a large majority of the population, such land could be put to better uses, such as for housing, schools, healthcare and other amenities to serve the people.

The land currently occupied by the golf courses could yield about 250,000 to 300,000 HDB flats, even after allocating part of the land to build schools, retail premises, parks, roads and other infrastructure. The number of flats that could potentially be developed on these golf courses could provide about 12 to 16 years of public housing supply.

There are also large tracts of land in Singapore that are zoned as Reserve Sites. These include reclaimed land and other state land in various parts of Singapore. If one were to view the online Singapore Master Plan on the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) website, these Reserve land parcels are in yellow on the online map. The Reserve land is part of the government’s land bank, and can be rezoned for other uses in the future.

Meanwhile, a significant amount of land, estimated at between 15 per cent and 20 per cent of the usable land in Singapore, is zoned for industrial use. These sites are mostly situated in the western region of Singapore, but they are also found in various locations around the island, including at the city fringe.

The factories and warehouses in the older industrial estates are ageing and could be technically obsolete. Furthermore, some of them are located near residential areas, such as at Paya Lebar, MacPherson, Kallang, Bukit Merah, Pasir Panjang and Bedok, where there is growing demand for housing.

Although it can be argued that these buildings provide business space for small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs), which in turn provides employment near the residential areas, some of those ageing factories were constructed at a time when Singapore was a low-cost manufacturing country.

But those days are gone. Those ageing factories were not built for modern high-tech industries, hence, may not be efficiently designed for modern uses.

Perhaps it is time to take a more holistic review of the industrial land policy in Singapore. Some of the ageing factories could be redeveloped for other uses, such as residential, commercial or a mix of residential and commercial space. The authorities could also provide incentives for the redevelopment or renovation of the industrial buildings to enhance them for more modern business uses.

TURN OLD TO NEW

Another possible place to look for land is old residential buildings.

The last major residential collective or en bloc sale bull run occurred between 2004 and 2008. It minted thousands of millionaires and contributed to the property market boom which ended with the 2008 global financial crisis.

Since then, however, the en bloc market has cooled down considerably, due to various cooling measures.

The Singapore population has been rising steadily in the past five decades and is expected to continue to rise. More private and public housing will be needed.

If older condominiums are to be part of the urban renewal process, plot ratios and the allowable building heights of the land of the older non-landed residential properties should be raised.

If not, they risk becoming relics of the past - especially when they stand next to newer buildings.

Nicholas Mak is Chief Research Officer at the property portal Mogul.sg.