'No subsidy, no deal': Shoppers fume as China's trade-in drive stalls – what's next to boost consumption?

The national trade-in programme has been reportedly suspended in parts of China, with funding shortfalls and system upgrades among reasons cited. Analysts say the public anger reflects the programme's popularity, but warn that sustaining spending momentum will require deeper reforms.

Workers at a chain electronic appliance store in Shenzhen prepare to scan QR codes for customers redeeming vouchers under China’s national trade-in programme. (Photo: CNA/Melody Chan)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SHENZHEN: It’s 9.58am on a Tuesday, and anticipation is building at a Suning appliance store in Shenzhen’s western Bao’an district.

Five sales representatives stand ready, phones in hand, as shoppers hover beside them in quiet urgency. In just two minutes, the scramble begins.

That’s when a limited daily batch of government vouchers drops, and they will race to help customers verify QR codes and redeem subsidies offering up to 20 per cent off new appliances like fridges and air-conditioners under China’s national trade-in programme.

CNA observed similar scenes playing out at other major home appliance retailers, including JD and Sundan. One store manager, who wanted to be known as Xian, said the walk-in queues only began in mid-June.

“Online redemptions have stopped because the money (for the next tranche of subsidies) hasn’t come in, so now everyone has to come down in person,” she told CNA.

The on-the-ground snapshot comes amid reports of subsidy suspensions in parts of China, frustrating shoppers. Retailers and officials cite reasons ranging from funding shortfalls to system upgrades.

The pauses have spurred creative workarounds as consumers look for ways to access the subsidies, while also drawing attention to alleged misuse of the scheme.

At the same time, analysts say the halts actually reflect higher-than-expected demand - an encouraging sign for Beijing’s flagship trade-in programme, designed to revive domestic consumption and reduce reliance on external demand.

“It means people are quite enthusiastic about the programme,” Zhou Xue, senior China economist at Mizuho Securities, told CNA.

But even as China pledges continued funding, observers caution that the trade-in scheme alone is a stopgap - broader efforts are needed to tackle structural challenges like a sluggish property market, weak job and income prospects, and ongoing tensions with the United States.

China needs to buy time, Chen Bo, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute (EAI), told CNA.

“This period is like a breather, because other policies are also being rolled out.”

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE SUBSIDISED

Launched in March 2024 to spur household spending, China’s national trade-in scheme offers cash rebates to consumers who swap old goods for new ones.

While the name suggests a trade-in is needed, many platforms and provinces offer 10 to 20 per cent off consumer goods even without one - broadening the programme’s appeal.

This year, the initiative is backed by 300 billion yuan in ultra-long-term special bonds, double the amount allocated in 2024. It has also expanded beyond home appliances and electric vehicles to include electronics such as smartphones, tablets, smartwatches and fitness bands priced under 6,000 yuan (US$836).

But headwinds have emerged in recent weeks, with consumers in provinces such as Guangxi, Jiangsu, Henan and Liaoning reporting that applications for subsidies under the scheme have been suspended.

Local governments have provided varying reasons. Authorities in Chongqing, Henan and Hunan cited “funds running dry”, while Jiangsu and Guangdong blamed “system upgrades” and “risk control enhancements”.

Authorities have pledged continued support and funding for the trade-in scheme. Still, frustration is bubbling online, with some Chinese citizens taking to social media to air their grievances.

“It’s ridiculous, I was about to make a purchase today and suddenly they halted it,” one user wrote on the social media platform Xiaohongshu.

“No subsidy, no deal,” another declared. A third user quipped: “Not buying saves me money - 100 per cent.”

Analysts say the pauses of the trade-in subsidies in some provinces are likely due to faster-than-expected uptake.

“If we’re seeing these pauses now, it suggests claims are coming in quicker than anticipated - meaning participation has exceeded expectations,” said EAI’s Chen, who further noted that provinces with tighter local finances, such as Jiangxi and Gansu, enacted the temporary subsidy halts.

Allan Von Mehren, chief analyst and China economist at Danske Bank, has a similar view.

“It shows that it’s working as intended – people are actually using it. Of course, if you run out of money, that could be a challenge,” he told CNA.

The trade-in scheme is funded through ultra-long-term special bonds, with co-funding from local governments under a 9:1 central-local ratio, and additional top-ups where needed, according to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC).

While some local governments have cited funding shortfalls for the subsidy pauses, analysts CNA spoke to were sceptical.

“Provinces like Chongqing and Jiangsu are financially strong … they can issue general local bonds to fund these expenses,” said Zhou from Mizuho Securities.

“I don’t think financing 10 per cent of the subsidies is a problem.”

Hannah Liu, a China economist at global financial services firm Nomura, believes that the roll-out is moving along at a “normal pace”.

The central government allocated 162 billion yuan for the subsidies in two tranches in January and April. A further 138 billion yuan is scheduled for release in the third and fourth quarters, with the next tranche set to roll out in July.

Liu added that April’s tranche was mostly used up by end-June.

“The quick take-up shows people are using the subsidies … if they weren’t, that would be a bigger concern,” she said.

Every yuan of government subsidy translated into roughly seven yuan of consumer spending, said Zhou.

According to the Ministry of Commerce, in the first five months of the year, the national trade-in scheme generated 1.1 trillion yuan in sales across five major categories - cars, home appliances, digital devices, e-bikes, and kitchen and bathroom upgrades.

Liu suggested the recent surge in claims is largely seasonal – driven by a flurry of events in May, including the 618 shopping festival and the Dragon Boat Festival holiday.

“There may not be particularly strong underlying demand directly tied to the subsidies,” she told CNA.

“If authorities had accounted for seasonal sales patterns, they might’ve staggered the allocations - less in Q1, more in Q2 and beyond.”

“That clearly wasn’t the case.”

OF WORKAROUNDS AND LOOPHOLES

Amid the subsidy halts in some regions, some enterprising Chinese consumers have found ways to work around the issue.

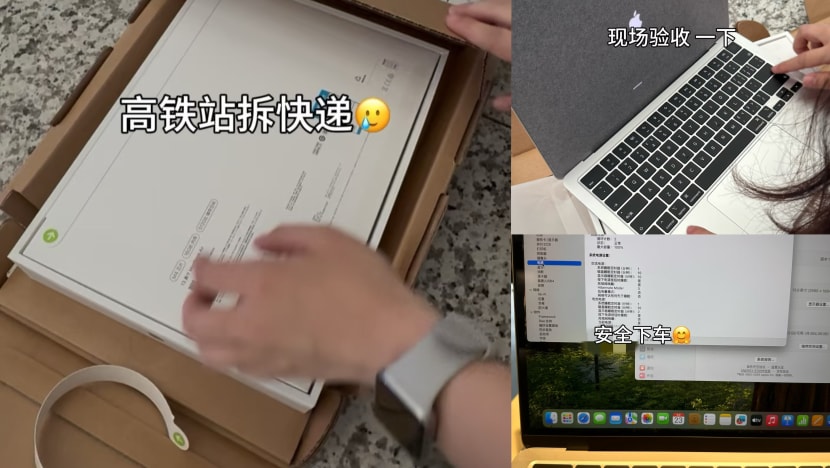

Among them is Guangzhou resident Wendy Huang, who had her eye on a 14-inch MacBook Pro listed on Taobao for nearly 13,000 yuan.

By stacking subsidies from the trade-in scheme with a platform discount, the 25-year-old corporate marketing employee could have snagged it for under 7,000 yuan, nearly half off.

It would have been her fifth purchase under the programme. But when she tried to confirm the purchase the next day, the deal had vanished. Subsidies for that category had been suspended in Guangzhou, though still available in neighbouring Shenzhen.

Rather than give up, Huang improvised. “The price was just too tempting,” she told CNA.

Instead, Huang redirected the laptop delivery to Shenzhen North High-Speed Rail Station. There, she met the courier, let him snap photos of the unboxing - a requirement for the rebate - and squatted by the platform to inspect the device.

“It was a bit of a hassle, and I had to pay for the train,” she told CNA. “But with a discount like that, it was absolutely worth the detour.” Her ticket cost around 80 yuan.

Huang isn’t alone in finding creative ways around the rules. On Chinese social media, users have been swapping tips on how to tap trade-in subsidies across provincial borders.

A Shenzhen resident, who declined to be named, told CNA he recently bought a 13-inch MacBook Air in his hometown of Shanxi and had his family mail it to him.

“It only cost around a few dozen yuan to ship,” he said, adding that he saved 20 per cent off the list price of 7,399 yuan - paying just 5,399 yuan.

But beyond workarounds, the recent subsidy suspensions have also spotlighted alleged misuse of the trade-in programme, particularly in the automobile sector.

Scroll through a Chinese secondhand car platform, and it’s easy to find thousands of listings for vehicles with barely any mileage - often just 100km to 300km on the odometer.

Dubbed “zero-mileage used cars” or “ling gong li er shou che” in Chinese, these listings have raised concerns that dealers are exploiting a loophole in the national trade-in scheme.

The playbook: buy new cars from automakers, register them under the names of relatives or employees to qualify for subsidies and sales bonuses, then resell them as secondhand - all without the vehicles ever hitting the road.

In May, Great Wall Motor chairman Wei Jianjun publicly called out the practice, estimating that “at least 3,000 to 4,000 vendors” are involved.

But industry experts told CNA the phenomenon is far from new.

“It’s nothing new, people have been doing this for years,” said Zhang Xiang, director of the Digital Automotive International Cooperation Research Centre at the World Digital Economy Forum.

Zhang said many dealers are rushing to act before the subsidies expire by year-end.

“Some operate secondhand shops themselves, offering a convenient channel to offload the unused vehicles and keep sales numbers up.”

Take, for instance, a new electric vehicle priced at 100,000 yuan.

A dealer buys the car directly from the automaker and registers it under a collaborator's name - often someone hired online - allowing it to be counted as “sold” and unlocking a manufacturer sales bonus of 1,000 yuan to 2,000 yuan.

The vehicle is then transferred to the dealer’s own or a partner’s secondhand platform and listed as a “zero-mileage used car”, with under 300km on the odometer. It's priced slightly below retail to attract buyers.

Meanwhile, the dealer scraps an old vehicle provided by the collaborator to qualify for the national trade-in subsidy, worth up to 20,000 yuan for EVs. The dealer often pays the person more than the scrap car is actually worth.

The result is still a tidy profit, thanks to the combined gains from sales bonuses and government incentives.

Zhang noted that while the practice may seem questionable, it is not illegal, as there are no rules requiring cars to clock a minimum distance before being resold.

Chen from EAI described it as a “by-product of extreme market competition”.

Competition has been intensifying in the world's largest auto market, with price wars that started in early 2023 showing little sign of abating despite concern among both government and industry.

“When car prices fall quickly, the combined value of factory rebates, government subsidies and secondhand resales can be more profitable than selling to actual customers,” Chen said.

Rather than stimulating genuine demand, Chen said such behaviour is distorting the market.

“It accelerates the drop in new car prices and ends up squeezing out quota in the primary car market - because buyers who would’ve purchased new cars are now getting them through secondhand channels at a discount,” he said.

Analysts acknowledged the difficulties in making the trade-in programme airtight.

“It's impossible to make a programme completely bulletproof,” said Danske Bank’s Von Mehren.

“Given the size of the Chinese market, it is not surprising that issues arise with a programme like this. Creativity runs high, and there are always attempts to find loopholes and ways to circumvent certain rules.”

FUEL FOR NOW, NOT THE LONG HAUL

While Chinese officials have moved to reassure the public that the trade-in programme and its subsidies remain on track, experts agree the current approach is not sustainable.

They warn that it offers only short-term relief, while pointing out that it is just one part of a broader push by China to address deeper structural challenges.

EAI’s Chen likened the scheme to “reigniting the engine” of domestic consumption - a short-term spark rather than a long-term fix.

He pointed to three persistent challenges weighing on China’s recovery - stubborn unemployment and stagnant wages, mounting corporate debt choking cash flow, and external headwinds such as escalating trade tensions with the US.

“In the long run, when we use subsidies, what we’re really doing is trying to reignite people’s desire to spend. But subsidies alone can’t fundamentally shift total demand,” said Chen.

He said the scheme provides some breathing room as concurrent efforts to bolster the Chinese economy - including settling commercial arrears to restore private sector confidence, boosting tech innovation, and stabilising the beleaguered property market - take deeper root.

Crucially, Chen believes it’s too early to assess whether the trade-in programme is working.

It will take one to two quarters after the subsidies cease to see if consumers are still motivated to spend, Chen said.

“The key test is whether the subsidies can unlock broader demand - demand that’s dozens of times larger than the subsidy itself. That’s what would show it worked.”

For Von Mehren, China is moving in the right direction, but must act with greater urgency.

He believes the property sector is one of the most pressing issues that must be addressed to revive confidence and get the economy moving.

China’s prolonged property slump remains one of the biggest drags on consumer confidence. In May, official data showed that new home prices fell 3.5 per cent year-on-year and 0.2 per cent from April - the 11th straight month of decline.

With housing accounting for about 70 per cent of household wealth, the downturn has eroded the financial security of many families, dampening their willingness to spend.

“I think (China) should actually recover a bit in order to get more confidence among people that the bottom has been reached,” Von Mehren said. “Because as long as you don't know if you reach the bottom, it creates uncertainty.”

Zhou Xue from Mizuho Securities said the current recovery in the property market remains “very fragile”, citing historically high inventory levels.

“There’s more local governments can do to support the market. And I think the best way is allowing them to raise more money from the bond market to support this programme.”

Even with the next tranche of subsidies expected to be released next month, Zhou predicts that, based on last year’s usage patterns, funds may run dry in some cities before September.

She expects authorities to respond by expanding the scheme - possibly into service-related categories such as tourism.

Public holidays are largely viewed as key drivers of consumption in China, offering concentrated bursts of economic activity as hundreds of millions of people travel, shop, and dine. This year, authorities have added two extra days to the statutory holiday calendar, raising the total to 13.

But Nomura’s Liu argued that service-related subsidies would be difficult to sustain, as rising demand could push up prices and dilute the stimulus effect.

Instead, she believes priority should be placed on the silver generation, referring to China’s fast-expanding elderly demographic.

“Those who have money are more inclined to spend - and that tendency is stronger among lower-income groups,” she said, noting that retirees make up a significant share of this segment.

“Nearly 70 per cent of them rely on monthly pensions of just a few hundred yuan. If they’re given more support, their marginal propensity to consume would be significantly higher.”

In the meantime, Chinese consumers are navigating the current subsidy landscape as best they can.

With the next round of government support on the horizon, some savvy shoppers are already holding off on purchases, waiting to capitalise on the upcoming injection of subsidies.

Huang, the Guangzhou resident, is among them. She’s not done shopping – just biding her time.

“I’ll wait.”