After a year of Russia's war in Ukraine, can China help to end the conflict?

China has the edge in its relationship with Russia, but this does not necessarily translate into an ability to end the war in Ukraine, experts tell CNA.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping talk to each other during their meeting in Beijing, China on Feb 4, 2022. (File photo: Alexei Druzhinin, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP)

SINGAPORE: It has been one year since President Vladimir Putin launched Russia's invasion of Ukraine in a pre-dawn address on Feb 24, 2022, in what has come to be widely criticised as an unprovoked attack.

As missiles fell over the nation of 44 million and gunfire rang out in the capital Kyiv, some observers were casting their eye back to a leaders’ summit a few weeks before that seemed to take on renewed significance.

Twenty days before the invasion, Mr Putin and China’s President Xi Jinping met and issued a joint statement declaring that the friendship between their countries has “no limits” and “no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation”.

Since then, while Russia has faced growing international isolation through sanctions and censure, the situation is very different when it comes to the relationship with its neighbour China.

Last year, trade between Russia and China rose 34.3 per cent year-on-year to a record high of US$190 billion. The Chinese yuan became the most-traded foreign currency on the Moscow exchange in October 2022.

In June 2022, reports started emerging that China had surpassed Germany as the largest buyer of Russian oil, while Russia had replaced Saudi Arabia as China’s largest crude oil supplier.

But are the two powers as aligned as this closeness suggests? CNA asked political scientists what China and Russia still need from each other one year into the invasion, whether their relationship could be instrumental to ending the war, and what this all means for the Indo-Pacific region.

CHINA’S STANCE, ONE YEAR IN

Despite Mr Putin’s invasion dragging on with no end in sight, most experts agreed that China’s position towards Russia has stayed largely unchanged since the start of the war.

China is relatively comfortable playing a “semi-neutral” role and that will not change much unless a dramatic need arises – such as Russia using nuclear weapons, said Associate Professor Matthew Sussex.

“China has essentially maintained a rhetorical commitment to the ‘no limits’ partnership with Russia, while trying not to be seen as coming down (too) firmly on any one side,” said the fellow at the Australian National University’s Strategic and Defence Studies Centre.

Associate Professor Chong Ja Ian of the National University of Singapore (NUS) said that while China remains generally supportive of Russia, it appears more careful about how to demonstrate this, particularly when Russia makes suggestions about nuclear weapon use.

China has also made adjustments like removing pro-Russian diplomat Le Yucheng from the position of Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, and appointing its US ambassador Qin Gang as Minister of Foreign Affairs, Professor Bo Zhiyue pointed out.

But Associate Professor Alexey Muraviev of Curtin University has observed a gradual shift in China’s stance over the course of the war.

“I think that Vladimir Putin convinced Xi Jinping that the war in Ukraine should be a swift and short operation resulting in Russia’s decisive victory. A year later, Beijing is pushing for a diplomatic solution (to) the crisis but stops short of accusing Russia as an instigator of the war,” he said.

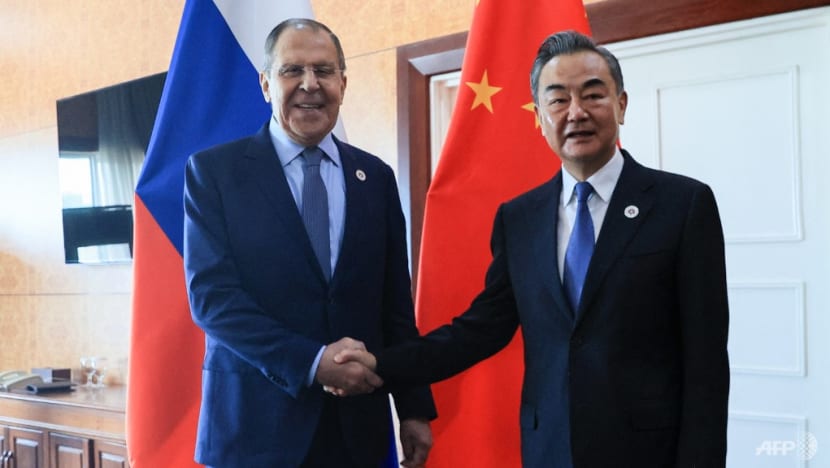

China said it would publish a proposal this week for a “political solution”, with Foreign Minister Qin Gang saying that Beijing would “offer Chinese wisdom for the political settlement of the Ukrainian crisis, and work with the international community to promote dialogue and consultation, address the concerns of all parties and seek common security”.

“China wants this war to end but it does not want to see Russia lose” as its defeat would leave China standing alone against a united West, said Assoc Prof Muraviev.

This may also explain concerns about Beijing supplying Moscow with military hardware, he added.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently voiced such concerns and warned of consequences should China do so, while Beijing has slammed the claims as false.

Prof Bo, founder and president of the Bo Zhiyue China Institute, assessed that while China’s leadership has been working closely with Russia, Chinese companies have been “very careful not to be dragged into the technical collaborations with military applications, unless they have clear instructions”.

SOUTHEAST ASIA’S POSITION AND INFLUENCE

More than 30 countries swiftly imposed sanctions on Russia in the days after the invasion. Singapore was the only one in Southeast Asia to do so, with Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan noting the country has “rarely acted” in this way.

Singapore has continued to highlight its position after announcing the sanctions. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said the country took a strong stand because it had “chosen principles”, while the Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that Russia’s decision to formally annex occupied Ukrainian regions violates international law and the United Nations Charter.

Other Southeast Asian countries have generally had an ambivalent reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, according to Assoc Prof Chong.

“On one hand, (they) feel that the conflict is far away and is of little direct concern. As a result, they are willing to take a passive position and side with the victor,” he said.

“On the other, Russian aggression has added to inflation woes, especially in terms of food and energy prices. Silence on the invasion also appears like silent acceptance of the violation of sovereignty through the use of force.”

Responses from the region have been varied. Aside from Singapore, no Southeast Asian country has directly condemned Russia, according to analysis by the Sasakawa Peace Foundation in Japan. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) expressed concern but did not condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in three foreign ministers’ statements last year.

However, there have been developments in the area of defence cooperation. Russia is traditionally Southeast Asia’s largest arms supplier. In July 2022, the Philippines backed out of a US$227 million deal for 16 Russian military helicopters, choosing to buy from the United States instead. Vietnam – an historic Russian ally – held its first large-scale international defence trade show last December in a bid to diversify supply.

There have been surprises too. For instance, despite its perceived closeness with Russia and China, Cambodia’s national position evolved from refusing to take sides, to Prime Minister Hun Sen taking a phone call with Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, an academic previously pointed out.

Russian narratives about the war, and their amplification by China, also seem to have had some traction in Southeast Asia, said Assoc Prof Chong.

These include the suggestion that the conflict was a result of provocation by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and that US presence in Asia is therefore “fundamentally destabilising”.

There is also a view in some quarters that Russia invading Ukraine is “little different from the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, or Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory”, which further limits support for Ukraine, he said.

“The range of mixed incentives across Southeast Asia may explain why regional states have been relatively quiet about the conflict and mixed in their voting on resolutions relating to the conflict and Russia at the United Nations,” said Assoc Prof Chong.

USEFUL NARRATIVES AND DISTRACTION

These narratives about the war point to how Russia’s invasion has been of some use for China’s strategic aims in the Indo-Pacific, by casting NATO and the United States as irresponsible, destabilising actors that provoked and prolonged the conflict in Ukraine, said experts. The conflict can also be a useful distraction.

“The current stalemate is a good thing for China, for it keeps (its) biggest neighbour occupied, while distracting the United States and also severely limits the ability of European countries to interfere in the Indo-Pacific region,” said Assistant Professor Benjamin Ho of the China Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

Assoc Prof Muraviev said that while Russia needs China’s political and economic support, China in turn needs Russia to protect its northern borders and keep the US involved in Europe’s strategic affairs.

“The more Washington and NATO get involved in the war over Ukraine with Russia, the more strategic freedom China may exercise in the Indo-Pacific, including vis-à-vis Taiwan,” he said.

But political scientists also questioned how much the situation in Ukraine has actually distracted from China’s moves in the Indo-Pacific.

China’s support for Russia has made public sentiment in Europe and North America more sceptical toward Beijing’s intentions, said Assoc Prof Chong.

Another expert said that Mr Putin’s failure to quickly accomplish his war aims and the unity of Western nations rallying around Ukraine have damaged China’s image.

“Western focus on Ukraine has not lessened opposition to Chinese regional aims,” said Mr James Carouso, a former US diplomat and senior fellow and chair of the Australia Advisory Board at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Instead, fearful that Russia has created a precedent for China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan are all increasing defence spending and military cooperation with the United States and each other, he said.

ADVANTAGE CHINA

China has also gained a strategic advantage from the shifting balance of power in its relationship with Russia, as a result of the international response to the war in Ukraine.

Asst Prof Ho said that Beijing is willing to live with the “messiness” of the conflict as long as it does not spill over into China, as it gains additional levers with Russia more reliant on Chinese economic support to prop up its export market.

Experts pointed to the oil and gas that China has been buying from Russia at discounted prices, as well as the greater influence that China has been able to project in Central Asia.

While China benefits from the cheap and reliable supply of oil and gas, Russia “desperately needs” that trade to offset the economic damage caused by sanctions, said Assoc Prof Sussex.

“The balance in the relationship is now heavily on China’s side, and it becomes more acute every week that the war continues,” he said.

“One reason for this is that there is simply no path back to ‘normality’ in Russia-West relations while Putin (or anyone who acts similarly) is in power.”

That leaves China as Russia’s “best remaining major friend”, said Assoc Prof Sussex.

A second reason is that Chinese investment in Russian extractive resources will be crucial if Moscow is to realise its dreams of becoming an “Asian energy superpower”, he said.

“That gives Beijing quite a lot of leverage as far as making sure Russia doesn’t compromise Beijing’s own interests in the general Indo-Pacific space, and also more specifically in Central Asia, where China is increasingly taking a more active role.”

But there are limits to the benefits of war for China. A broader conflict is not in its interests given its extensive efforts to build trade and investment dependencies among European states, said Assoc Prof Sussex.

The war has also led to rising prices on strategic items such as energy, agriculture and mining products in China, causing inflationary pressure, said Dr Xu Le, lecturer in strategy and policy at the NUS Business School.

Rising geopolitical tensions have added momentum to the deglobalisation trend, necessitating China’s gradual change in its growth model from an export-led economy to a domestic-driven one, she added.

NO END IN SIGHT

Despite China having the edge in its relationship with Russia, that does not translate into an ability to bring the war to an end, the experts said.

“I think the view that Xi can essentially pick up the phone to Putin and tell him to end the war is a big overstatement – and a misunderstanding – of the nature of China’s influence,” said Assoc Prof Sussex.

“China certainly has deep and long-term structural influence over the fate of the Russian economy, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into the ability to affect shorter-term choices the Kremlin makes about its strategic policy in Europe.”

That said, one area where Beijing would have influence is by issuing “quiet warnings” against Russian nuclear escalation or provoking NATO to enter the war, he added.

China could potentially be a mediator in the conflict, and President Xi has been reported saying that China is willing to play that role. But experts pointed out that if even if it were in a position to, Beijing is in no hurry to force an end to the war.

China may even be unwilling to use any leverage it has as this may suggest that Mr Xi has miscalculated in deepening ties with Mr Putin, said Assoc Prof Chong.

Ultimately, the experts agreed that it comes down to whether the Russian president will be willing to listen to and accept any proposal made.

With Mr Putin’s fortunes tied to the outcome of the war, failure would weaken him personally. “He is therefore unlikely to be receptive to Chinese insistence that he should bring a war he is currently losing to a swift conclusion,” said Assoc Prof Sussex.

Mr Carouso put it starkly: “Only Russia can end the conflict in Ukraine. China doesn’t offer sufficient incentive to change Putin’s mind, even if Xi chose to try.”

AFTER THE WAR

Looking ahead, most experts expect China and Russia’s closeness to last beyond the war in Ukraine, as long as the two leaders remain in power.

This trend predates the invasion of Ukraine, with Mr Putin long speaking of a pivot to Asia as a vital nation-building task for Russia, said Assoc Prof Sussex.

China will have opportunities after the conflict, in the form of “binding Russia more tightly to Chinese preferences” and playing a role in Ukraine’s reconstruction, but it risks being drawn into Russian security traps, especially related to border insecurity.

He pointed to China’s “stern” warning that it would not tolerate military adventures that threaten Kazakhstan at the September 2022 summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, of which Russia is a member.

“What that demonstrates is that there will increasingly be boundaries drawn up in the ‘no limits’ partnership – with the key factor being that those boundaries will mostly be dictated by Beijing, and not Moscow,” Assoc Prof Sussex predicted.

But Asst Prof Ho sounded a more cautious note, saying: “There is no love lost between Russia and China, as both countries are not natural allies of one another.

Russia is severely weakened from the conflict in Ukraine while China is “not the economic juggernaut of the past”, he said.

“It will be foolish for both Beijing and Moscow to only rely on one another and not to source for other partners in the rest of the world.”