Commentary: Trump’s unconventional diplomacy will come at high cost for US partners

US President Donald Trump is turning to trusted envoys such as his son-in-law to achieve diplomatic breakthroughs. But these efforts come at a cost to America’s allies, argues Kevin Chen from RSIS.

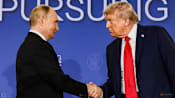

Russian presidential envoy Kirill Dmitriev, US President Donald Trump's special envoy Steve Witkoff (front right) and son-in-law Jared Kushner (left) attend a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia, Dec 2, 2025. (Sputnik/Alexander Kazakov/Pool via Reuters)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: With the ink drying on the Gaza peace plan, two real estate developers from New York are eyeing a deal to end Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Steve Witkoff, the Middle East peace envoy for United States President Donald Trump, and Mr Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, made diplomatic history in October when they convinced Israeli and Hamas leaders to agree to a 20-point plan that led to a ceasefire and the release of all remaining Israeli hostages. While tensions persist and many details left to finalise, it was still a remarkable breakthrough that raised hopes of ending the Gaza conflict.

This is not Mr Kushner’s first foray into foreign policy. During Mr Trump’s first term, he was the driver behind the Abraham Accords, which sought to normalise diplomatic ties between Israel and three Arab states.

Mr Witkoff and Mr Kushner now aim to replicate their Gaza success in Ukraine. The pair were in Moscow on Tuesday (Dec 2) to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin but left with no deal.

Yet, with the talks prioritising speed and secrecy, America’s European allies risk becoming sidelined from security in their own region. This could also hint at how Washington might handle a conflict in Asia.

DEALMAKERS, NOT DIPLOMATS

It seems clear why Mr Trump prefers dealmakers to handle negotiations instead of regular bureaucrats. What he seeks is not a comprehensive deal between conflicting parties – traditional diplomacy moves too slowly for him.

Instead, he wants breakthroughs that create a basis for future talks and offer him a political victory. Trusted envoys would be attuned to his wishes.

There may also be an element of competition in Mr Trump’s approach. Rather than fielding a single team via Mr Kushner and Mr Witkoff, there are at least two other parties that are engaged in talks over Ukraine. These are Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who met with European officials in Geneva, and Army Secretary Daniel Driscoll, who met with Russian officials in Abu Dhabi.

Some analysts have suggested that Mr Trump may be intentionally pitting groups against each other to see who produces the best results. From a business standpoint, this may make sense; less so from a diplomatic perspective.

It creates challenges for coordination and messaging. The confusion surrounding the initial revelation of the 28-point Ukraine peace plan was a vivid illustration of this issue.

SECRECY AND CONFUSION

A key concern about the earlier plan centred on the inconsistent messaging from Washington.

Following the plan’s announcement on Nov 19, the State Department professed no knowledge of it. Axios reported that US officials told their European counterparts that it was “not a Trump plan.” Several US Senators attending the Halifax Security Forum claimed that Mr Rubio had called and told them that the plan “was not the administration’s plan” but a “wish list of the Russians.”

Even though the State Department and Mr Rubio later asserted that the plan was authored by the US, the damage had already been done. External observers were aghast at the “messy” coordination of the entire process, where one part of the US government appeared to be unaware of what another was doing.

The contents of the plan were equally controversial. It called for Ukraine to cede land that it currently holds in the Donbas region, to limit the size of its postwar military, and abandon any attempt to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Ukrainian and European officials argued that it amounted to capitulation to Russia’s demands.

Things got worse after transcripts of calls involving Mr Witkoff and two Russian officials close to Russian President Vladimir Putin were published. In the transcripts, Mr Witkoff instructed his Russian counterpart Yuri Ushakov how to engage Mr Trump, while Mr Ushakov and economic adviser Kirill Dmitriev discussed how to ensure the peace plan closely reflected Russia’s demands.

Leaving European nations out of talks about European security only deepened their suspicions.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ASIA

Secrecy and exclusivism appear to be a feature of the US dealmaker approach: move fast, seal the deal and then leave the difficult work to be sorted out afterwards.

Much of the controversy surrounding the plan could have been mitigated if European officials had been clued into the discussions from the start. However, Europe’s exclusion was apparently by design, with Army Secretary Driscoll telling European officials they were left out of initial talks to avoid having “too many cooks.” It took a concerted effort by European diplomats to even gain a seat at the negotiating table after Nov 19 to soften its terms.

The implications of this approach do not stop in Europe. In the event of a conflict in Asia, even US allies may find themselves excluded from peace talks while Washington deals directly with the conflicting parties. As evidenced by Europe’s experience, they may then face an uphill battle to get a seat at the negotiating table and influence over the terms.

A besieged party could find itself forced to accept and implement decisions it had no say in.

Ironically, Moscow seems to understand the value of working with diplomatic partners more so than Washington. Russian Secretary of the Security Council Sergei Shoigu met Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi around the time of Mr Witkoff and Mr Kushner’s meeting with Mr Putin, with the two holding “in-depth exchanges” on Ukraine.

The dealmaker approach worked in Gaza and may yet pay dividends in Ukraine. However, the costs of this approach are also becoming apparent. Terms can be sorted out at the negotiating table, but it is much more challenging to regain the trust lost by disdaining US allies and partners.

Kevin Chen is an Associate Research Fellow with the US Programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore. He writes a monthly column for CNA, published every first Friday.