Five hot-button issues likely to feature during Malaysia’s GE15 campaigning

Cost of living, corruption and political stability are some of the issues expected to weigh heavily on Malaysians casting their ballots.

SINGAPORE: Well before Malaysia goes to the polls on Nov 19, political parties are already wrangling over key issues.

The economy and inflation typically rank high, as the war in Ukraine rages on and Malaysia’s government and central bank warn of slowing growth next year.

Voters also want political stability, frustrated with the politicking that has rocked the country since the opposition’s historic defeat of the long-ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) at the 2018 election.

Then there is the issue of corruption. A big part of why UMNO lost in 2018 was that its key members were embroiled in graft, resulting in multiple court cases against them.

Ahead of the upcoming polls, the controversial non-delivery of navy ships despite billions of ringgit spent, is yet another factor that might affect voter sentiment on the issue of mismanagement.

CNA dives into five hot-button issues surrounding Malaysia’s 15th General Election:

COST OF LIVING

While Malaysia’s economy is expected to expand 4 per cent to 5 per cent next year, extended conflicts and supply chain disruptions around the world mean prices - especially for food items - have been creeping up.

"The top issue (in the election) would be socioeconomic well-being which is rapidly deteriorating," Dr Oh Ei Sun, a senior fellow with Singapore's Institute of International Affairs, told Reuters.

On Oct 7, the Malaysian government unveiled a budget of RM372.3 billion (US$80.06 billion) for 2023.

RM55 billion will be allocated for government subsidies, aid and incentives, including RM7.8 billion under a cash handout programme that is expected to benefit 8.7 million people.

Another RM2.5 billion in welfare aid is set to help about 450,000 low-income households, while the income tax rate for middle-income individuals will be reduced by two percentage points.

While Malaysia’s Parliament was dissolved shortly after, rendering the proposal moot, the finance ministry has insisted the budget will be retabled after the election.

The Democratic Action Party (DAP), part of the opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition, had urged then-Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob not to waste MPs’ time in tabling and debating the budget if he planned to dissolve parliament.

But the finance ministry rejected such criticism, arguing that it was important for investors’ confidence as well as to allow them to plan their next steps for the year ahead.

Observers told CNA that the latest budget could be described as “populist” as it involves cash handouts and reducing taxes for a large portion of voters.

Those set to benefit include voters who are typically UMNO supporters, solidifying support for Mr Ismail Sabri, said Mr Hafidzi Razali, a senior analyst with strategic advisory firm Bower Group Asia.

But Mr Hafidzi said voters will still consider whether they trust the current government to deliver on its promises, factoring in alternative proposals by opposition coalitions.

On Oct 20, PH announced key themes of its election manifesto that included helping people ride through the high cost of living due to rising inflation.

Mr Ismail Sabri wasted little time in launching a salvo, saying on the same day that the opposition’s election manifesto in the previous election was full of empty promises that left many in the lurch.

It has been said that PH's failure to fulfil a long list of electoral pledges has tarnished the coalition’s - now back under the leadership of former deputy prime minister Anwar Ibrahim - credibility.

The opposition had only offered empty promises, Mr Ismail Sabri said, comparing it to his latest budget that is ready to be implemented.

POLITICAL STABILITY

The opposition’s victory at the 2018 election, which had unseated the UMNO-led Barisan Nasional (BN) coalition after 60 years, was heralded as a new dawn for Malaysian politics.

But less than two years into a five-year mandate, voters saw it all disappear.

Infighting over who would succeed Mr Mahathir Mohamad as Prime Minister and a political manoeuvre dubbed the “Sheraton Move” saw the collapse of the PH government, replaced by a new coalition Perikatan Nasional (PN) led by Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu) president Muhyiddin Yassin.

This change in administration was widely criticised as a betrayal to the people’s mandate in the 2018 election, which rejected scandal-hit BN as the federal government.

After months of political bickering within the PN government and the growing loss of confidence in the leadership of Mr Muhyiddin, especially in the way the government handled the COVID-19 pandemic, the prime minister finally resigned in August 2021.

Mr Muhyiddin’s departure saw the return of BN to the apex of power with the appointment of Mr Ismail Sabri as the third prime minister in the last two years.

Despite its successful efforts in stabilising the government, especially by working together with PH through a Memorandum of Understanding on bipartisan cooperation, Mr Ismail Sabri’s administration was not free from internal problems.

Pressures from segments of the UMNO top leadership, with constant hype that the government was still shaky and in need of a new mandate, finally prompted Mr Ismail Sabri to dissolve parliament and make way for GE15.

The caretaker prime minister hopes that this election will finally give his party a popular mandate and help it dispel accusations that his administration, like the one before it under Mr Muhyiddin, has been a backdoor government.

Analysts believe that the perception of political instability might hurt voter turnout in GE15, especially among those who traditionally vote for the opposition, due to disillusionment with the country’s political situation since the 2018 general election.

A low voter turnout, however, is generally perceived as advantageous for UMNO.

A recent poll by the Merdeka Center showed that only 40 per cent of youths in Malaysia said they were very likely to vote, although it did not give reasons why.

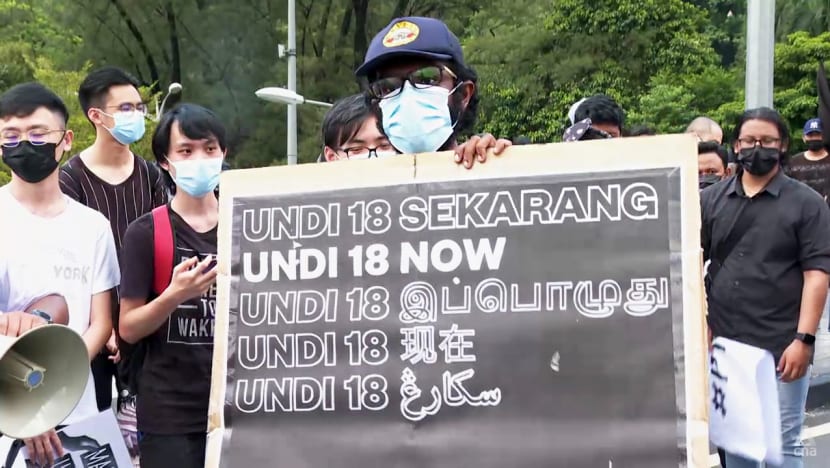

Voter apathy is becoming a key issue despite the recent move by Parliament to amend the federal Constitution to allow for the lowering of the voting age from 21 to 18.

The move means that the number of eligible voters has increased to 21 million from 15 million in the previous election.

While the recently passed anti-party hopping law was aimed at preventing MPs from switching parties, helping to avert political instability as seen in the Sheraton Move, it has not removed all future uncertainties.

For instance, the law does not have any provision to prevent parties from moving en bloc from one coalition to another, which can cause the collapse of a standing government.

“This creates more political turbulence than in the past and more uncertainty as a result,” said political scientist Norshahril Saat of the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in a CNA commentary on Sep 3.

UNDELIVERED WARSHIPS

A report tabled to Parliament on Aug 4 by Malaysia’s Public Accounts Committee (PAC) created more turbulence, when it highlighted how the country had not received six littoral combat ships (LCS) despite a contract for them worth RM9.13 billion was signed nearly a decade ago.

According to PAC, the government has paid RM6.08 billion - or two-thirds of the total cost - to local contractor Boustead Naval Shipyard (BNS), although none of the ships has been delivered.

BNS, which classifies the LCS a frigate-class vessel that can perform complex naval missions, was supposed to deliver all but one of the ships by August 2022.

A declassified report on the LCS project has also revealed Ahmad Zahid's personal involvement in it, despite the former defence minister's constant denial.

On Aug 16, former BNS managing director Ahmad Ramli Mohd Nor was charged with criminal breach of trust over the deal. He pleaded not guilty.

The PAC findings sparked a rare rebuke from retired servicemen, traditionally seen as a government vote bank. They urged the relevant authorities to pull their act together and ensure that the ships will be built as soon as possible to replace the navy’s ageing assets.

Observers think that this latest multi-billion ringgit scandal could hurt the reputation of Mr Ismail Sabri’s administration and UMNO, as the opposition could seek to capitalise on the controversy.

The DAP has called for the resignation of the attorney-general and the chief of the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission for their supposed inaction over the scandal.

This scandal and other pending corruption trials involving UMNO’s top leaders could impact the party negatively and lower BN’s chances of a clear election victory, noted Dr Norsharil in the CNA commentary.

UMNO president Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, who is facing 47 charges of criminal breach of trust, corruption and money laundering over the use of funds in a charity foundation linked to him, had been very vocal in pushing for snap polls, ostensibly to seek a fresh mandate from the people.

An election had not been due until September 2023, but Mr Ismail Sabri faced pressure from some factions of his ruling coalition, including from Ahmad Zahid, to hold the vote earlier.

THREAT OF FLOODS

Some segments of the public are also frustrated that Mr Ismail Sabri buckled under the pressure to call polls so close to the monsoon season, which last year killed 54 people and caused RM6 billion in economic damage.

Malaysia’s Meteorological Department has ruled out major flooding up to early November, but warned that the weather has become difficult to predict.

Campaigning and polling day will likely happen amid heavy rainfall during the northeast monsoon season, which typically lasts from October to March.

But the Meteorological Department said it is still too early to predict the weather during the election, Bernama reported on Oct 26.

The department said weather patterns cannot be determined for now because the country is still in a monsoon transition phase that is expected to last until next month.

The opposition has criticised the government’s decision to hold the election during the monsoon, arguing it was risking voters’ wellbeing. Ministers from the PN coalition wrote to the king to say the timing was inappropriate.

Then-Health Minister and UMNO member Khairy Jamaluddin also waded into the debate, saying an election would take away manpower needed to manage evacuation centres and schools - typically used as voting centres - that act as shelters.

But UMNO’s top leaders like Ahmad Zahid shot back at critics of early polls by describing the flood narrative as a “myth”, put forward by the opposition as an excuse to delay the election.

“The real concern of the opposition is that Malay voters, who make up the largest percentage of the country’s population, are less interested in supporting the coalition when BN is beating the election drum,” he said.

Still, some residents in flood-prone areas CNA spoke to said they were frustrated that the polls would be held during this period. Some lost entire home appliances and valuables to the floods last year.

Political analyst Wong Chin Huat, of the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network's Asia headquarters at Sunway University, said BN’s gamble of early polls could backfire, especially if voters are angered by flooding during campaigning.

“UMNO may justify the early poll using various reasons such as how the opposition is in disarray and their voters are demoralised now, the coalition government (led by Ismail Sabri) is unstable and that the economy will get worse next year,” he told CNA.

“But none of these can be sure to offset the risk of having voters turning against BN for insisting on GE15 amid floods.

STATUS OF BORNEO STATES

Away from peninsular Malaysia, political parties in the states of Sabah and Sarawak are contending with a different type of perennial issue: The status of the two states as equal partners with Malaya as the original founders of the Malaysian federation in 1963.

When the federation was formed that year, the Malaysian Constitution listed the Borneo states separately from the rest, on par with Malaya and Singapore as spelt out in the Malaysia Agreement 1963 (MA63).

This gave the states a high degree of autonomy and jurisdiction over the administration of most state matters and resources in Borneo, save for national issues of defence and foreign policy.

In 1976, the Constitution was amended to include Sabah and Sarawak with the rest of the states.

This amounts to a “downgrade” for Sabahans and Sarawakians, said Professor James Chin of Tasmania University in a commentary for CNA.

“Ownership of Malaysia’s oil and gas, most of which comes from Sabah and Sarawak, was given to Petronas - in return for only 5 per cent oil revenue, for example,” he wrote.

“Although oil and gas were not mentioned in MA63, the public sentiment is that these massive resources were used to develop the peninsula at the expense of East Malaysia.”

Over the years, politicians have pledged to address this issue, with the PH government’s first attempt to revert to the original wording in the Constitution that would restore the two states’ status as outlined in MA63.

At the Sabah state election in 2020, the incumbent state governing coalition - which did not include parties that formed the federal government - played up Sabah’s identity.

The upcoming election is no different.

On the weekend after polling day was announced, major parties flocked eastward to garner support of traditional kingmaker state Sabah. With 25 parliamentary seats at stake, a win in Sabah is seen as crucial for any coalition looking to form the next government.

Both BN and PH have dangled a deputy prime minister position for a candidate from Sabah if they win the election, eager to secure a decisive partnership even before voters head to the polls. The post has typically only gone to someone from peninsular Malaysia.

But observers say such an appointment is just decorative, and would not really benefit people in Sabah and Sarawak.

Instead, voters in Borneo want greater autonomy from the federal government, better infrastructure and development, and a bigger share of Malaysia's oil and gas revenue that come from the vast resources in Sabah and Sarawak.

“I think this offer of deputy premiership for East Malaysia is a very politically expedient and, shall we say, a convenient one, because in Malaysia the post of deputy prime minister is essentially powerless,” said Dr Oh Ei Sun.