IN FOCUS: Should social media be banned for teens in Singapore?

Australia has implemented a social media ban for under-16s. While such a move is well-intentioned, experts warned it may push youths to darker corners of the internet.

More countries are implementing measures for youths to verify their ages on social media. (Illustration: CNA/Clara Ho)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: At first, it appeared to be an innocent livestream of someone chatting to viewers while eating.

But the scene quickly turned into one of horror when 13-year-old Shrihaan Thakar realised that the livestreamer he was watching had begun hitting his cat.

“I found it very disturbing and cruel,” said the Secondary 1 student, who immediately reported the video.

“I tell myself to be aware that there might be bad things happening and to report them immediately,” he added.

Shrihaan says he is not alone. His friends have reported seeing disturbing and radical content on social media platforms like TikTok and X, he said.

“For students or people my age, I don't worry much ... But for younger children in primary (school), I worry a little bit.”

Online harms - such as scams, sexual, and violent content - are a growing concern for governments worldwide.

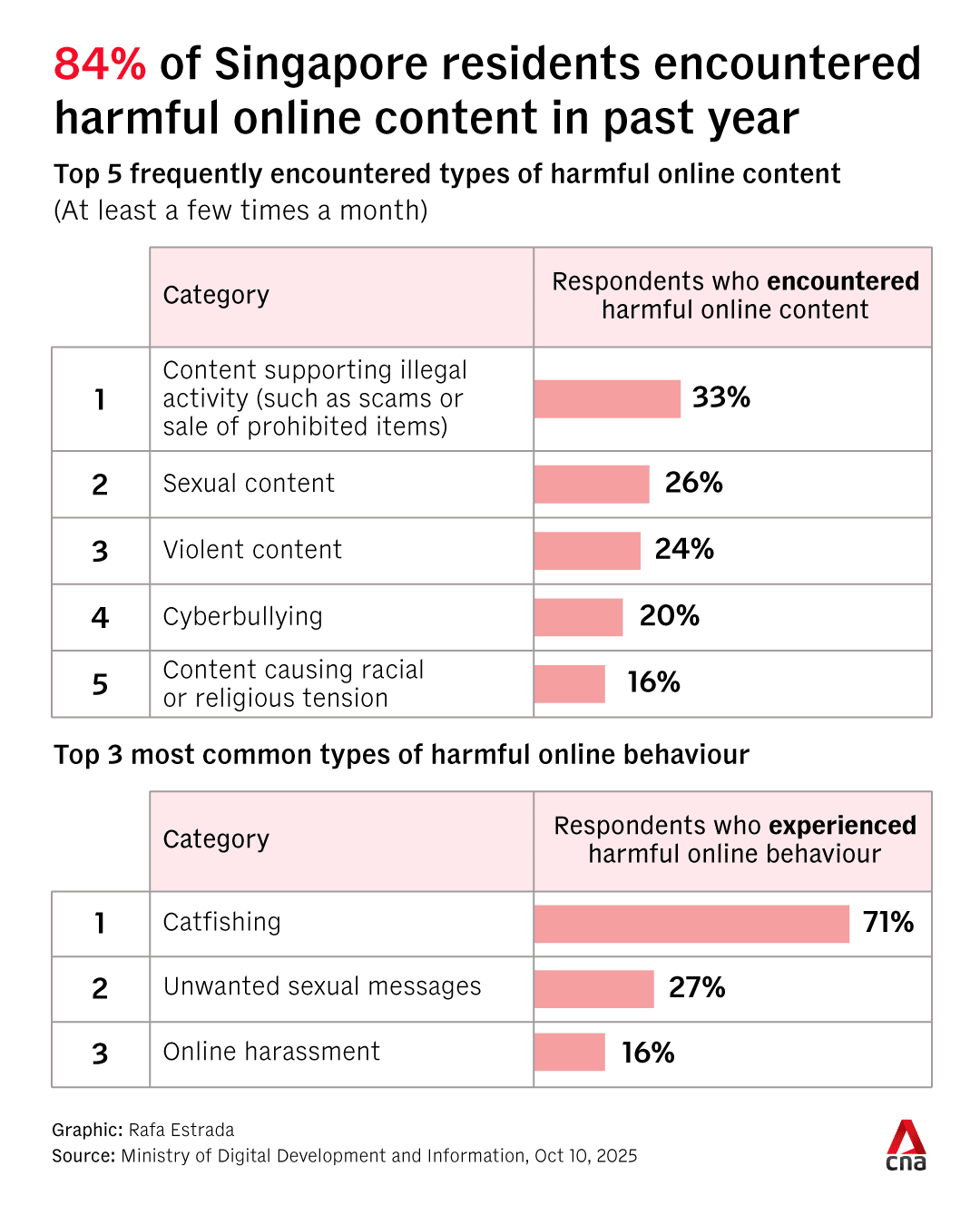

In Singapore, more than four in five residents reported encountering harmful online content in the past year, according to a recent survey conducted by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information (MDDI).

Some countries have implemented stricter age-assurance measures for youths to verify themselves on social media.

Australia took the lead. Since Dec 10, it has restricted users under 16 from creating social media accounts.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s government had proposed the landmark law, citing research showing harms to mental health from the overuse of social media among young teens, including misinformation, bullying and harmful depictions of body image.

France, Spain, Italy, Denmark and Greece are jointly testing a prototype for an age verification app. Malaysia announced plans in November to ban social media for those under 16 from 2026.

Some parents have expressed hope that a similar ban would be introduced in Singapore, but experts cautioned that such sweeping measures have their drawbacks, including driving teens towards darker corners of the internet.

THE CASE FOR A BAN

One benefit of a social media ban is the signal that it sends, said Dr Jean Liu, Associate Professor of Psychology, Health and Social Sciences at the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT).

“By implementing a ban, we send a strong message that society prioritises the well-being of the next generation over profits,” she said.

Such policies could also allow families and schools to rely on legal backing to manage their children’s digital activities, she added.

The minimum age to create a social media account on most platforms is 13. But even without a ban, children already find ways to create accounts, said Ms Chen Xiuying, a stay-at-home mother of three.

“But with a legal ruling set in place, there's a legal framework to actually push the stop button or pull the clutch if the child is running too close to the edge,” she said.

When the eldest of her three sons was in lower secondary, he nearly mailed money to a YouTuber based in Europe. The content creator had asked viewers for donations so he could buy mayonnaise for his birthday.

Ms Chen, 45, only found out when her son called her from the post office, saying that an adult had to be present for him to mail the cash.

Although her son was well-intentioned, the incident highlights how youths can easily be influenced by what they watch on social media, she said.

It is “wild out there on the internet”, and parents who are busy or not digitally savvy may be unaware that their teenagers are being exposed to dangers on social media, she said.

“People are very wary about letting their kids run outside physically. But I think they don't realise that online is where the danger lurks.”

Online harms go beyond cybercrime and violent content.

In a recent study by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), non-consensual sexual content, the promotion of dangerous behaviours such as self-harm, and targeted harassment were ranked among the highest in terms of perceived severity.

It is in such a hostile environment that additional guardrails, such as bans, sound appealing to parents like Ms Chen.

She likened a ban to age-restriction measures at the movies: “Would you allow your kid to go and watch an R21 movie from the get-go? No, right? And your child can access R21 movies and porn very easily on social media. Without any intervention, they can be exposed to it.”

Senior clinical psychologist at Promises Healthcare, Dr Sandor Heng, pointed out that children and youths are especially vulnerable to the effects of social media.

“Where the research stands, our brain will fully mature at 25 years old, and what we know in terms of developmental milestones at that developmental sensitive window of adolescence, that's where social influences have the biggest impact,” he said.

The mechanisms in social media – whether it is likes, comments or swipes – provide a sense of instant gratification.

At the same time, social media exposes young people to more social comparisons, including the fear of missing out or body image issues, he said.

“It's a combination of immediate gratification plus comparisons possibly beyond what you would normally compare with in offline settings.”

While problematic screentime use is not considered a standalone diagnosis, there is growing recognition of it.

This is because of observable features such as the loss of control and the prioritisation of use above other activities, said Dr Heng, who sees a sizeable number of young patients facing social media addiction.

BLUNT APPROACH

Psychologists Dr Heng and Dr Liu agreed that a ban on creating a social media account has its limitations.

For one, youths may find ways to bypass age-assurance measures. Youths may use a virtual private network (VPN) or ask adults to help create accounts.

“I can see where the idea comes from – it's really to protect. But then again, I do feel like this might be a very blunt approach, because it will be hard to enforce,” said Dr Heng, who specialises in treating addictions.

Dr Liu noted that bans focused on account creation may not accurately reflect actual usage patterns, as most youths watch, rather than create videos on content-sharing sites.

However, some platforms still allow users to view content without having to create an account.

“This approach seems outdated when you think about how children and adolescents use social media today. These bans target an earlier generation’s usage patterns, when adolescents were active on social networking platforms like Facebook and Instagram,” she said.

When Australia first introduced plans to restrict users under 16 from creating accounts for platforms such as Instagram and TikTok, parents were very enthusiastic, said Professor Amanda Third, co-director of the Young and Resilient Research Centre at Western Sydney University.

“But it's been very interesting … to watch the debate unfold. As we get closer to the implementation of the legislation, people have begun to get their heads around it, to think more deeply about how this will work and how it will impact them,” Prof Third told CNA shortly before the ban was enforced.

She pointed to a poll conducted by a public sector consultancy in Australia, which found that one in three parents responded that they would help their kids circumvent the social media restrictions.

According to the report, many parent and carer participants believed their children were already using social media safely with supervision. Others thought that enforcement would be too difficult, given children's entrenched smartphone use and social pressures.

Under the Australian law, which was passed in November last year, social media platforms must enforce age-assurance measures to prevent minors from logging in – or face a fine of up to A$49.5 million (US$33 million).

Prof Third, who previously signed an open letter to Mr Albanese outlining reasons against the ban, said the logic of excluding young people from the platforms and asking platforms to meet their obligations to children felt “very contradictory”.

“Banning children from the platform punishes children. It doesn't punish the platforms. It lets the platforms off the hook, actually, because they no longer have to think about children,” she said.

“And what I worry is that if they don't have to think about children, when children do come online at age 16 - or whatever age governments deem appropriate - they'll come into environments that are much worse than they currently are.”

Dr Chew Han Ei, a senior research fellow and head of Governance and Economy at IPS, agreed that when tech companies put their resources into age verification, fixing the source of online harms, such as algorithms, may end up on the back burner.

Another concerning possibility is that young people may relocate to less regulated platforms, said Dr Chew, who was also the principal investigator of the IPS research on perceived severity of online harms.

An example is the closed-messaging platform Telegram, which made headlines in Singapore in 2019 for hosting an obscene chat group called SG Nasi Lemak.

“It could be that the online harms on the regulated platforms will drop because the young people are no longer on it, but that's what you can see … what we might not be able to see is the migration to other platforms where the online harms could be happening,” he said, adding that the regulatory eye on those platforms may not be trained.

“So it could be a zero-sum. In society, the harms could still be happening, but it's just that we don't see them. That’s a hypothesis.”

A SAFE SPACE

At the same time, experts noted that there are positive effects of social media that teens may be denied if hard rules on their social media use are implemented.

Youths use social media to connect with others and find support. “But by banning (social media), you are taking away all that, the bad and the good,” said Dr Chew, adding that teenagers are at the age where they are learning digital skills.

Ms Shubhada Jayant Bhide, Shrihaan’s mother, said a blanket approach would not work as she feels that social media use among teens cannot be avoided.

“If they are not going to use it, their peers, their friends, are still using it. And honestly, they have seen their parents also using it. So it's very difficult to have that complete control in place,” she said.

She added that social media has its educational purposes too.

Shrihaan, for example, often uses sites like YouTube as a knowledge base, said the IT professional who is in her 40s.

“He's very interested in geography. So watching different travel videos, learning about different countries, their demographics, and all that. YouTube has been a very, very good source of information, especially when it comes from those authorised channels,” she said.

For many other teens, social media is a space where they can seek solace and find community.

Most youths in Singapore might be familiar with r/SGExams on Reddit.

Since its inception in 2017, the community on Reddit has grown to over 180,000 users who come together to discuss academics, ask for advice and bond over casual conversation. In a week, the forum receives around 500 posts and more than 8,500 comments.

“I didn't think that it would grow to become that big,” said Mr Irwen Zhao, the president of SGExams, explaining that the community came about when moderators on the main Singapore subreddit excluded students because they were “too spammy”.

Now, r/SGExams has become a sounding board for many youths, especially when they face issues that they might not be able to resolve on their own, said Mr Zhao, 25, who first joined as a moderator in 2018 when he was a student.

Mr Zhao said that the community prides itself on having a “strong moderation policy” to ensure a safe space for young people to come together. For example, they have a strict no doxxing rule in place. A group of about 10 volunteer moderators also looks at user reports to take down posts that may be inappropriate.

Although users under 16 only make up less than a quarter of the community, they are also the group that needs advice and experience from the community the most, he said, adding that they may have nowhere to go if they were to be banned.

“Some youths really do need that space. And without that, they could be in very dark places,” he said.

COULD A BAN WORK IN SINGAPORE?

In January, Minister of State for Digital Development and Information Rahayu Mahzam said in parliament that Singapore was engaging its Australian counterparts and social media platforms to understand their views.

An MDDI spokesperson told CNA that authorities are monitoring global developments and studying the experiences of other jurisdictions, including Malaysia, Australia, the UK and the European Union.

Some parents worried that their children’s early exposure to smartphones in Singapore could limit the effectiveness of a social media ban.

A 2019 survey by Google found that children in Singapore receive their first internet-connected device at eight years old, making them among the youngest in the world to go online.

Family content creator Alex Lee, 40, gave his 12-year-old son Daken his first smartphone last year.

“We try not to give him so early. But sometimes it's a bit no choice, because he has to go out on his own. So it's more for communication,” he said.

Phones, not social media, are the real problem, he said.

Mr Lee is no stranger to the social media world. He has over 500,000 followers on Instagram and over 300,000 on TikTok, where he posts videos about parenting and family life with his wife and two sons.

At home, his children use the TV in the living room if they want to browse content on YouTube.

But smartphones may give kids the chance to hide, he said.

“Even some sort of games like Roblox have a lot of bad influences inside. So it’s not really social media, but more of them having the freedom to hide and use their mobile phones. Then you can’t control the content that they are consuming,” he said.

Already, schools have stepped up measures to limit phone use: from next year, the use of smartphones and smartwatches will not be allowed for secondary school students during school hours, including recess, co-curricular activities and supplementary lesson time.

Daken told CNA a ban on social media would cause “big changes” in his life. The soon-to-be secondary school student enjoys using YouTube to watch videos about musical jokes and parodies, he said.

“Because I can't listen to music. I can't see the new stuff. But it makes sense because children watch inappropriate things sometimes,” he said.

NOT A “ONE OR ZERO” SOLUTION

IPS’ Dr Chew said that protecting young people from online harms should not be “one or zero”.

“Either you have, or you don't have; either you ban, or you allow. But maybe we have to explore the kind of gradations – what's in-between.”

In Singapore, MDDI announced new age assurance requirements that took effect from Mar 31 to restrict those under 18 from accessing and downloading age-inappropriate apps.

These requirements will also be extended to designated social media services which attract many children, the spokesperson from MDDI said, adding that consultations with platforms will take place over the coming months.

The authorities have also stepped up efforts to tackle online harms.

In November, parliament passed a new Online Safety (Relief and Accountability) Act, which establishes a new Online Safety Commission.

The commission has the power to force platforms to remove harmful content and unmask anonymous perpetrators.

Ultimately, a safer online space can be created when digital literacy is accessible for both young people and their parents, said Dr Chew.

“Right now, the bottleneck is guardians and parents – they don't know what to do,” he said, adding that they could be inundated with information from various agencies and well-meaning places.

“The seniors, the boomers like me, need technical skills to help the young people, or the very young children, know how to introduce the technology slowly, know how to activate the safety features, know how to have conversations with young people about their technological use.”

In September, a survey by MDDI found that only 37 per cent of parents in Singapore felt confident in their ability to guide their child’s digital habits.

In the same survey, about 57 per cent of parents wanted stronger legislation from the government to protect their children online.

Age-based guidance could help, in the same way the Ministry of Health has rolled out screen time guidelines for kids under 12.

“We help them in a tailored way and in a more focused way. So easy-to-implement, (and) don't inundate with information,” he said.

SIT’s Dr Liu, who co-wrote a positive use guide for the Infocomm Media Development Authority’s Digital for Life movement, said that children need scaffolding – just like how they learn to cross the road.

“Adults first make a judgment on whether they seem ready, then walk beside them as they navigate online spaces, before gradually stepping back,” she said.

“Instead of age-based bans, we should focus on how to support ‘L-plate’ learners as they navigate social media for the first time.”

Other experts emphasised the role of technology companies.

“The best solution here is not to take young people out, but to keep them in and demand across national borders that technology companies meet their responsibilities to the young users of their digital products and services,” said Australia’s Prof Third.

In response to queries, Google, which owns YouTube, said it has invested heavily in designing age-appropriate experiences and industry-leading content controls and tools that allow parents to make choices for their families.

According to Google, age assurance solutions will be implemented across its products in Singapore in the first quarter of 2026.

CNA understands that TikTok restricts the experience for users under 16. For example, direct messaging is not available to those under 16, and their accounts and content are automatically set to private.

Additionally, TikTok identifies age-restricted content during livestreams, and they are not recommended to people aged between 13 and 17. According to TikTok, the app can only be used by those who are 13 or older, and the platform removes accounts when it believes that the user is under the minimum age.

CNA has contacted Meta for comment.

The joint effort of demanding better standards across countries and platforms may take more energy than an outright ban, said Prof Third.

“But I think the effort of coming together, creating transnational standards, and demanding that platforms design to those standards is probably energy much better spent.”