‘On edge’, pressing ahead: What 2026 reveals about China’s next phase

From US rivalry and cross-strait tensions to expanding global influence, the coming year will test China’s ability to hold course amid mounting strain, analysts say.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

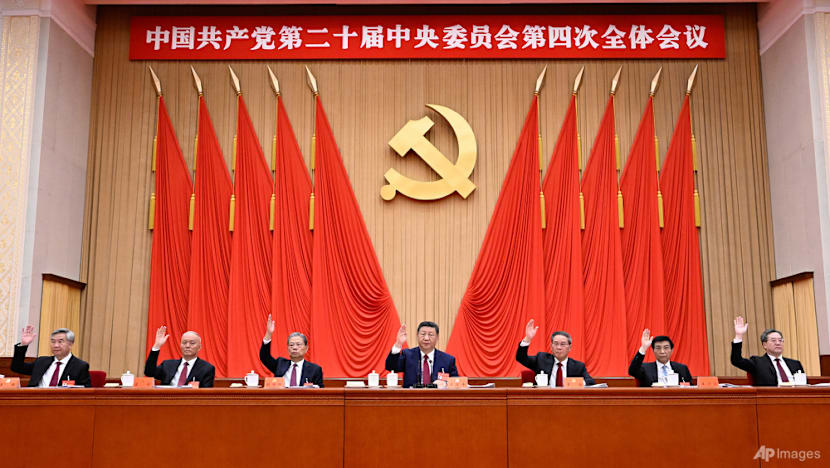

BEIJING: As China steers into 2026, it does so in a year of careful calibration, analysts say - a critical passage towards 2027, when the Communist Party’s 21st Party Congress will unveil the next slate of top leaders and could see President Xi Jinping seek an unprecedented fourth term.

The pre-Congress year typically offers early signals of elite alignment and succession dynamics, experts say, making 2026 a key period for reading political cues in Beijing.

Against this backdrop, China is expected to project greater confidence abroad - from hosting the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Shenzhen to pushing to shape global rules.

“China is moving from a cautious rise to a more confident projection of power,” said Jonathan Ping, an associate professor at Bond University in Queensland, Australia.

He added that 2026 will be a year in which Beijing presses to position itself as a rule-shaper rather than a rule-taker.

The world will also be watching how US-China relations evolve, with potentially up to four face-to-face meetings between US President Donald Trump and Xi expected over the course of the year.

Taiwan is expected to remain a persistent flashpoint.

Analysts told CNA that pressure on Taiwan could likely intensify in 2026, even as Beijing seeks to avoid a direct military confrontation ahead of 2027 - a year often cited as a benchmark for China’s military modernisation.

Internally, the realities are far more complex. Beijing is confronting mounting pressures, from economic strain and demographic decline to a tightening political environment, noted Chong Ja Ian, an associate political science professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and a non-resident scholar at Carnegie China.

“The question is whether or to what degree (the Chinese government) is able to change the more troubling long-term trends,” Chong said.

How China navigates these cross-currents will offer early clues to the sustainability of its ambitions in a more contested world, he added.

STEADYING THE SINO-US “GIANT SHIP”

After a bruising year of tit-for-tat trade actions in 2025, 2026 will offer important signals on whether both sides can move beyond tactical stabilisation, analysts say.

“There is a lot of talk about a reset in US-China relations, including efforts to stabilise ties,” said Chong.

“But both Beijing and Washington see themselves locked in long-term competition, whether in technology, supply chains or relative global standing,” he added.

A meeting between Xi and Trump in late-October yielded commitments to resume more regular high-level dialogue, ease trade tensions, and stabilise bilateral relations after months of escalation.

Xi used a nautical metaphor to characterise the relationship, telling Trump that China-US ties were like “a giant ship” - whose course needed to be properly set and carefully steered by both sides to ensure stable and constructive relations.

Trump later said that he would make a state visit to China in April, adding that Xi would reciprocate with a visit to the US later in the year.

The two leaders could also meet at multilateral gatherings like the APEC summit hosted by China in November and the Group of 20 (G20) summit hosted by the US in December.

These high-level engagements could offer a stabilising anchor, said experts.

“The overall trajectory of bilateral relations is expected to remain relatively stable over the coming year,” said Ren Xiao, a professor at Fudan University’s Institute of International Studies.

Beijing now enters these discussions with greater confidence, Ren said, arguing that years of trade confrontation have altered the balance of leverage between the two sides.

The tariff war, he noted, “has forged a more equal footing in bilateral relations than previously existed, with the US now fully recognising China’s formidable strength”.

In recent rounds of trade friction, China has responded with counter-tariffs and other targeted measures, including steps affecting US soybeans and rare earths, tools that analysts said have strengthened Beijing’s bargaining position.

“China has seen it all before and is less worried now. Moreover, it holds trump cards that lend it further confidence,” he added.

The outlook for 2026 will also be shaped by domestic priorities on both sides, Ren noted - with Beijing focusing on advancing its 15th Five-Year Plan objectives, while Washington turns its attention to the 2028 presidential election cycle.

Any easing in ties is likely to be tactical rather than transformative, said Ping from Bond University.

“China wants recognition as a peer power and (greater) leeway to shape regional norms without direct US interference,” Ping said.

But ideological divides, US alliance commitments in Asia, and zero-sum competition in technology and security - particularly over advanced chips and supply chains - remain immovable constraints, he added.

Trust-building is further hampered by political behaviour on both sides, Chong said, noting that “both the Xi leadership and the Trump administration have a record for walking away from agreements” - a pattern that could fuel distrust and make durable stabilisation harder to achieve.

Analysts said Sino-US ties in 2026 are therefore likely to centre on managing rivalry rather than resolving it, as both sides prepare for deeper strategic contests ahead.

EXPANDING GLOBAL CLOUT

China is expected to use 2026 to further widen its global footprint, with November’s APEC summit in Shenzhen offering a prominent platform.

The gathering will allow Beijing to showcase its development narrative, technological strengths and diplomatic ambitions, particularly to emerging economies across the Indo-Pacific and the Global South, analysts said.

That push will build on initiatives Beijing has rolled out more recently on the global stage.

At the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in September, Xi unveiled China’s Global Governance Initiative (GGI), presenting it as a proposal to make global governance more fair, inclusive and responsive to the needs of developing countries.

The GGI builds on earlier proposals such as the Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative, underscoring Beijing’s ambition to play a more proactive role in global agenda-setting.

Analysts said 2026 will be a key test of how far Beijing can translate that vision into practice.

China will seek to institutionalise its influence by presenting its governance and development model as pragmatic and equitable for emerging economies, said Ping from Bond University.

Beijing, he added, is likely to frame the GGI as an alternative to Western-led frameworks, highlighting areas such as development finance, digital governance and climate cooperation tailored to Global South priorities.

The Global South broadly refers to developing countries that are poorer, have higher levels of income inequality and lower life expectancy.

Hosting APEC in Shenzhen will also allow China to advance narratives of tech-driven connectivity and inclusive growth, Ping said, while promoting ideas ranging from expanded BRICS+ engagement and yuan-based trade mechanisms to new Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) sustainability standards and proposals for AI and data governance under Chinese leadership.

Still, China’s expanding outreach is not without friction.

While Beijing increasingly sees itself as a champion of the Global South, its appeal remains uneven, said Chong of NUS.

“China’s growth story has strong appeal for countries in the Global South with more developmentalist and authoritarian outlooks,” Chong said, but he cautioned that Beijing’s expanding presence has also generated unease in some quarters.

Concerns include the mixed record of Chinese firms on labour standards, environmental protection and technology transfer, as well as fears that Chinese exports are crowding out local industries in developing markets, he added.

At the same time, China’s financial firepower is no longer what it was during the early years of the BRI.

While Beijing has delivered major infrastructure projects, it is now less able - or less willing - to commit vast sums of funding, instead recasting the initiative around “small but beautiful” projects, Chong said.

How China navigates these constraints while pursuing its global ambitions in 2026 will shape how credible and sustainable its push to expand influence ultimately proves, he added.

STABILITY OVER STIMULUS

Economic growth will remain a central pillar of China’s agenda in 2026.

After setting its GDP growth target at around 5 per cent for 2025, analysts expect a similar benchmark to be carried into the new year, reflecting Beijing’s preference for continuity and control rather than dramatic recalibration.

China has offered its clearest signal yet of how it intends to steer the economy following its annual Central Economic Work Conference, held in Beijing from Dec 10 to 11.

The agenda-setting meeting, attended by the country’s top leaders, laid out policy priorities for the year ahead.

Analysts said the official readout struck a familiar tone of confidence and resilience, reaffirming commitments to boost domestic demand, stabilise foreign investment and shore up key sectors. The emphasis, they noted, was on fine-tuning policy rather than unleashing sweeping new stimulus.

2026 could clarify the direction of China’s growth model.

“The moment probably marks a crossroads over whether the Chinese leadership truly wants to steer the world’s second-largest economy towards domestic consumption, continue with an export-led model, or persist with a dual-circulation approach,” said Lim Tai Wei, a professor of East Asia at Soka University.

Beijing has stepped up efforts to spur consumption in recent years - from subsidies and trade-in schemes to rhetoric around “new quality productive forces” - partly to offset vulnerabilities stemming from external pressures and persistent supply-side imbalances, Lim noted.

Yet significant headwinds remain.

Analysts said the more pressing challenge lies in deflationary pressures that continue to weigh on confidence.

“Whether the GDP deflator turns positive again will be the most important signal in 2026,” said Gary Ng, senior economist at Natixis and a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies.

Looking ahead, Ng expects policymakers to rely on a calibrated mix of fiscal and monetary tools to cushion growth at the margins, but sees little appetite for a large-scale stimulus push.

“The pressure will be tougher next year with a range of problems,” he said.

“However, the likelihood of a major stimulus remains low, as policy priorities are more focused on technology and security than on hitting headline GDP targets,” he added.

He added that the 15th Five-Year Plan, set to begin in 2026, is likely to prioritise longer-term structural goals - including innovation, advanced manufacturing and ageing - over short-term demand support.

While markets are watching closely for stronger pro-consumption measures, “it is not in sight so far”, he said.

Beijing may also intensify efforts to curb excessive competition in certain sectors, but Ng noted that industrial capacity remains a strategic asset.

“Industrial capacity does not run counter to China’s geopolitical leverage,” he said, arguing that maintaining production dominance in emerging sectors increases global reliance on Chinese supply chains and limits incentives to scale back output.

At the same time, rising trade barriers are expected to complicate the outlook, with new tariffs emerging not only from the United States but also from countries such as Mexico and members of the European Union, Ng added.

CROSS-STRAIT VOLATILITY IN FOCUS

Cross-strait tensions are expected to remain a central fault line in 2026, a year closely watched for signals of intent and posture ahead of 2027 - a benchmark US officials often cite for the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) capabilities related to Taiwan.

A draft Pentagon report said “China expects to be able to fight and win a war on Taiwan by the end of 2027”, Reuters reported in December.

Earlier in November, Taiwan President William Lai said Beijing was pursuing a goal to “complete unification with Taiwan by force by 2027”.

The remark was later amended on his official platforms to clarify that China was preparing for such an option rather than signalling a fixed timetable for action.

China has set 2027 - the centennial of the founding of the PLA - as a milestone for modernising its military.

“There is some misunderstanding about the 2027 window for Taiwan. It is a planning parameter, not a deadline,” Chong said, adding that Beijing’s aim is to ensure it has the necessary capabilities by that point should it choose to act.

“Having the capability does not equate to using it,” he said.

Any attack or blockade of Taiwan would carry enormous risks and uncertain outcomes, Chong added, noting that even without military parity, Taiwan and its partners could take steps to significantly raise the costs for Beijing.

“The risk of failing to control Taiwan at an acceptable cost could fall outside the risk appetite of China’s leaders, even if they possessed significant capability,” he said, stressing that invasion and occupation require different capabilities and should not be conflated.

Beijing regards self-ruled Taiwan as an inalienable part of China under its one-China principle.

Analysts expect pressure on Taiwan to intensify in 2026.

Beijing is likely to lean more heavily on coercive measures to signal resolve while stopping short of war, said Ping.

“Beijing will likely intensify coercive measures - including military drills, economic pressure and cyber operations - to demonstrate resolve without triggering a hot war,” Ping said.

Indicators to watch include sustained PLA joint exercises simulating blockade scenarios, expanded missile deployments in China’s coastal provinces such as Fujian, and closer Sino-Russian naval coordination, he said.

Regional dynamics add further complexity. Tensions between China and Japan have flared in recent months after comments by Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on a potential Taiwan contingency drew sharp rebukes from Beijing, prompting an exchange of diplomatic protests and further straining already fragile ties.

Ping warned that potential Japanese countermeasures - including enhanced missile defences and new security arrangements - could further raise tensions.

INTERNAL PRESSURES AND POWER POLITICS

Domestic politics are also set to loom large in 2026, a year that traditionally offers early clues about elite alignments ahead of the Communist Party’s next leadership transition during the 21st Party Congress, due in 2027.

Xi is already serving an unprecedented third term as China’s top leader, and observers said there has been little public evidence of a successor being groomed or positioned.

That has fuelled expectations that he could seek to extend his rule into a fourth term, further entrenching his central role in the political system.

Recent years have also seen high-level purges, particularly within the PLA and the defence establishment.

These moves have drawn added attention with 2027 marking the PLA’s 100th anniversary, a symbolic milestone that analysts said could bring renewed emphasis on loyalty, discipline and military modernisation.

“I would argue that the purges and lack of a successor indicate Xi’s confidence in his grip on power,” Chong from NUS said. "As long as that grip holds - and I expect it to in the short term - China’s willingness to press its maritime claims and expand its military capabilities is likely to persist."

Uncertainty, Chong added, only begins once Xi is no longer central to the political equation.

“When that might be is anyone’s guess. It could be 2026, but that is unlikely. Xi appears healthy and firmly in control,” he said.

Beyond elite politics, analysts warned of deeper risks linked to economic and technological change.

Local government debt, property sector stress and weak consumer confidence could converge to strain fiscal capacity and fuel social discontent, while advances in artificial intelligence could displace jobs in lower-skilled service sectors, said Ping from Bond University.

Accelerated industrial consolidation risks marginalising smaller firms and widening regional inequality, noted Ping.

“Unlike external flashpoints, such pressures quietly erode the foundations of China’s global ambitions and (could) constrain Xi’s ability to sustain assertive statecraft over time.”

Asked to characterise China’s outlook in 2026, analysts offered assessments that captured both ambition and unease.

For Lim of Soka University, the year is about “seizing the moment”.

With China occupying a prominent position in an increasingly multipolar world, he said maintaining - or improving - that standing will require careful navigation of shifting domestic and global currents.

For Chong, the prevailing mood is more taut. The phrase that best describes China in 2026, he said, is “on edge” - a reflection of pressures building simultaneously at home and abroad.

Taken together, their assessments point to a China entering 2026 with confidence and ambition, but also a keen awareness of the internal and external strains that make the year ahead both opportune and fraught with risk.