Commentary: GE15 – The rise of PAS as a major power and the end of Mahathir’s legacy in Malaysia

The rise of PAS as a major power broker at the federal level and the unceremonious end of Mahathir Mohamad have major implications for Malaysia’s future, says James Chin.

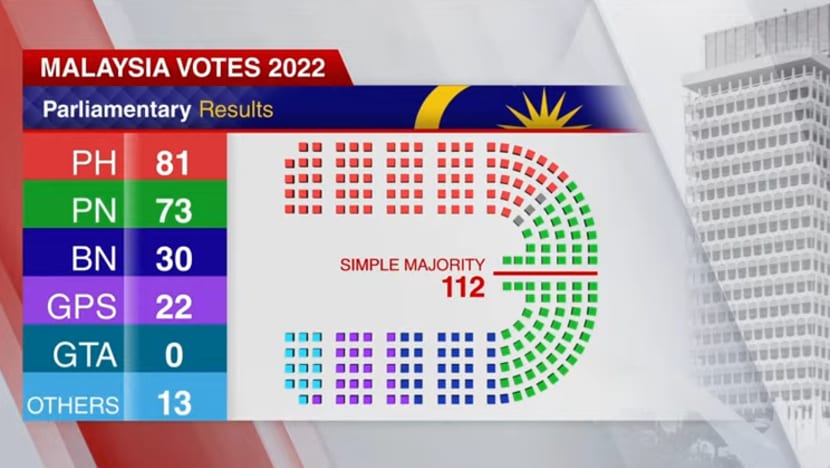

KUALA LUMPUR: Results of Malaysia’s 15th General Election (GE15), which started coming out on Saturday (Nov 19) night into the wee hours of Sunday, have been shocking. Analysts will spend years poring over Malaysians’ rejection of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and the embracing of Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) in the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition.

While Anwar Ibrahim and Muhyiddin Yassin jostle to form the next government, two things stand out about changes in the racial and religious political landscape: The rise of PAS as a major power broker at the federal level and the unceremonious end of Mahathir Mohamad’s brand of Malay nationalism.

These have major implications for the country as it steadies itself to grapple with global economic headwinds and geopolitical tensions.

RISE AND RISE OF MALAYSIAN ISLAMIC PARTY PAS

Pakatan Harapan (PH) may have won the most seats as a coalition, but the big winner is clearly PN component party, PAS - with a stunning 49 seats.

Before GE15, it was widely understood that PAS and its brand of conservative Islam was mainly restricted to the northern Malay heartland states of Terengganu, Kelantan, Perlis and Kedah.

It was never expected to be a federal politics player or bring home more than 10 per cent of the 222-seat parliament. In the last three general elections, PAS won between 18 and 23 seats.

The only explanation for their exceptional showing in GE15 would be a massive swing among existing voters and - more importantly - new voters, for it to have won outside its traditional strongholds.

For example, PAS won two seats in Penang, widely considered to be one of the most liberal Malaysian state with the only Chinese chief minister in the country. Notably, it unseated PH’s Nurul Izzah Anwar from the Permatang Puah “family seat” that had been occupied by Anwar Ibrahim, his wife and most recently his daughter.

Early reports indicate that new young voters also supported the party, although youth voters did not come out in large numbers.

We are seeing a sea change in Malaysian politics. PAS’ brand of conservative religious politics has become more attractive; political Islam has become mainstream in Malaysia.

IMPLICATIONS FOR MALAYSIA’S FUTURE

This has enormous implications for Malaysia’s future. Analysts said it will be challenging for PH to garner enough support to form the government despite its 81 seats, even if Anwar said early Sunday morning that it did.

Muhyiddin’s PN coalition trails with 73 seats but it will secure the 112-seat majority needed if it partners with other parties and coalitions that have ideological differences with PH. So, PAS could be part of the new coalition that will rule Malaysia over the next few years.

PAS’ electoral success gives it political strength, when its 49 seats dwarf the 24 seats won by Muhyiddin’s Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu). It can ask for key ministries with the potential to fundamentally change Malaysia if it pushes for more religion-based public policies.

For example, influence over the education portfolio could shape the thinking of the next generation. PAS has already successfully built a solid core of support in the Malay heartland. Since the 1980s, PAS supporters have actively established private kindergarten and tahfiz (religious schools). The few hundred thousand students who went to these schools are now voters or even politicians.

Some may argue that PAS cannot do real political damage, going by the actions of PAS ministers in the federal governments for the past two years. But this is misleading when PAS could now constitute at least a third of any ruling coalition – no prime minister can ignore such a large segment.

A MORE MODERATE PAS?

The real issue is whether PAS will moderate its position now that it has become mainstream.

In the past, it could ignore the non-Malay community. In GE15, PAS president Abdul Hadi Awang made offensive remarks about the Chinese community but could ignore any criticism that did not come from its voter base.

The biggest fear Malaysians hold about PAS influence in any federal government, besides the imposition of more religious rule, is that PAS’ shadow over the federal government might scare away foreign investment.

States ruled by PAS do not have much foreign investment, viewing “spiritual development” as more important than economic development. That is one reason why Kelantan and Terengganu remain as some of Malaysia’s poorest states.

END OF MAHATHIRISM

This GE also marks the end of Mahathirism. Mahathir’s long shadow in Malaysian politics was decisively rejected by the voters and his brand of Malay nationalism was rejected outright.

Mahathir not only lost his Langkawi seat; his son and political heir, Mukhriz Mahathir, also lost his Jerlun seat. In fact Gerakan Tanah Air, Mahathir’s coalition, lost all their seats.

The defeat was no ordinary defeat. In Malaysia, all candidates must put up a cash deposit before they can run. They only get back their deposit if they win 12.5 per cent of the votes in their contested constituency.

Mahathir’s Langkawi loss was his first electoral defeat in 53 years, finishing fourth in a five-cornered fight. He only managed to secure 4,566 votes, or 6.8 per cent of the votes, less than what was required to get his deposit back.

Likewise his son Mukhriz also lost his deposit, suggesting that the Malays do not support a Mahathir dynasty.

Because of this massive defeat and rejection, Mahathir’s political legacy is tarnished forever. He should not have tried to make a comeback in this election. History will now record a sad ending to his political career.

At 97, it is not possible for him to try another comeback. Had he stayed away, history might have looked upon him more kindly.

In the coming days, more will be said about GE15 but at the end of the day, what people will take away from this election is the rise of PAS and changes in the racial and religious political landscape, and the sad ending of Mahathir.

James Chin is Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania and Senior Fellow at the Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia.

.png?itok=imeZiA5w)